In This Together: School Librarians Help Address Learning Loss, Upheaval

Educators greet returning students and ease their anxieties while addressing the COVID slide.

|

Illustration by Monica Garwood |

As schools reopen, either virtually, in-person, or some combination of the two, many educators hope the focus will quickly shift from facilities, PPE, and cleaning methods to students, learning, and social-emotional needs.

At the same time, they’re grappling with where students are, academically and emotionally, six months after the abrupt shift to online learning. Meanwhile, the pandemic that has impacted so many families rages on.

School librarians are creating plans to greet their returning students, ease their anxieties, and address whatever learning gaps widened during the spring and summer. In fact, librarians are uniquely qualified to help students this fall, says Bill Bass, innovation coordinator for the Parkway School District in Missouri.

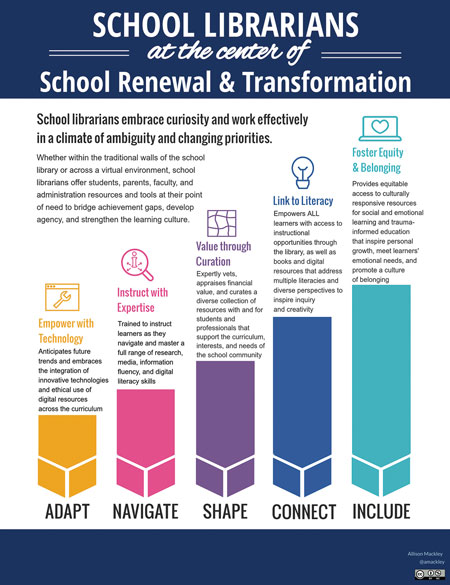

“Especially in this time of uncertainty, librarians have never been more critical to the nation’s schools,” Bass said in the new report from EveryLibrary Institute, “School Librarians and the COVID Slide.” “As master curators, we rely on librarians to sift through the abundance of information and digital noise. They are essential in helping teachers and students understand how to find and utilize high-quality digital tools and content.”

“Librarians have a flexible and broad view of their school,” Bass maintains. “They see everyone who is in that school and can really help connect the dots for teachers around technology and access to content.”

By late July, although most librarians still didn’t know their school’s opening plan, they were already working to meet student needs as they began to understand them, according to an online poll by School Library Journal.

Some plans to address the COVID slide were simple and direct: “Reading, reading, reading.” Other survey respondents mentioned putting together book giveaways and creating home learning kits that could be jammed with activities and games for students.

READ: Texas High School Teacher Zooms Into Remote Classes from U.S. Historical Sites and Landmarks

EveryLibrary’s report quantified the work librarians had done during remote schooling. More than 80 percent of respondents to that study said they provided curated resources for at-home activities, nearly as many shared community resources, and six out of 10 offered technical support. Almost half of librarians reported co-

teaching a class, while slightly more than one in 10 offered students makerspace events and gaming.

Measuring learning loss

Every year, educators fight the “summer slide,” where experts quantify the learning loss students experience as anywhere from a few weeks to several months. In normal times, the extent of learning loss for older students is even greater, research shows. But with schools shifting abruptly, and for the most part not smoothly, to distance learning in the spring, bigger learning gaps than seen in a typical summer are expected in fall 2020.

Learning loss in part will be impacted by how a school’s online learning program unfurled and how vigorously students participated. Early estimates from the EveryLibrary report predicted students would return to school this fall with about 70 percent of a typical year’s English learning gains. (In math, the gap is expected to wipe out half a year of learning.) With many states canceling or postponing assessments, it may be even harder for teachers and librarians to determine exactly where to start when students return to learning in the fall.

Researcher Chris Minnich, the CEO of NWEA, a nonprofit that creates assessments for growth and proficiency for K–12 students, expects that the COVID-19 learning loss will hit younger students hardest, especially those who are acquiring basic skills. Students already facing steep inequities may be more affected, he adds. In some grades, students may lose an entire year of learning.

“We’ll start with kids wherever they are,” says Jody Timmins, media coordinator at the South Mebane (NC) Elementary School, part of the Alamance-Burlington School System. Her school is planning to run classes at half capacity, and she expects to be back in classrooms doing lessons on research and digital citizenship. Her library will not be open, but she will do a form of curbside checkout, bringing requested books to students’ classrooms.

The school last conducted data benchmarks in January, and Timmins says most educators expect students to be right at that same level when school returns. Because students will do half their work at home, she expects to provide a lot of resources that allow teachers to personalize education for each student.

One private school librarian says her school regularly does assessments, so she expects a new set of tests at the beginning of this year will provide a road map for educators. “We’ll determine by assessments where they are and then move on,” she says.

|

click to enlargeInfographic from EveryLibrary Institute’s “School Librarians and the COVID Slide” report. Infographic by Allison Mackley, courtesy of EveryLibrary |

During the summer, Michelle Davis, librarian at Abingdon (VA) Elementary School, delivered free books to about 100 students and used the school’s Facebook page to help drive students and families to the town library’s holdings. If Davis’s school begins the year online, she’s ready to roll out some online lessons that might better reflect home life, such as work that can be easily overseen by an older sibling instead of requiring a parent.

“I’m doing high-quality read-alouds and picking books that will be timeless,” she says.

“Be generous and gentle”

Like many librarians, Ariel Dagan is worried about the emotional state of his students, especially if they start school online. Dagan is the library media specialist at the Tri-County Regional Vocational Technical School in Franklin, MA, which has 1,000 students and 17 different programs. Students typically spend one week in the classroom taking core subjects and one week in shop, learning a trade.

“I had to work really hard to find content,” he says of the spring, citing both students’ varied interests and need for technical information. He found himself recommending the NPR podcast How I Built This.

READ: After Crisis, Opportunity: Embracing Antiracist Teaching

Beyond the challenge of delivering remote, hands-on learning tools to students, “Kids don’t have daily routines, and we have some kids who are challenged,” Dagan says. He has tried to show them how to tap into virtual hangouts to recover some connection with students while they are physically away from school.

“Kids who are stressed aren’t going to be able to learn,” a New York City school librarian told SLJ. School officials don’t always appear to realize the enormity of how the global pandemic has scrambled students’ feelings, not just their schedules, she added.

“Honestly, I think learning loss is the least of our worries,” she says. “It’s essential to give them space to talk about how they are feeling. If things are falling apart, we have to take care of them rather than push on with a lesson.”

One respondent to SLJ suggested schools take the whole first month this fall to address students’ social and emotional needs.

Librarian Marta Rivas worries about how young students at the private Shady Hill School in Cambridge, MA, will get to see and know their teachers with masks. In 2019–20, students at least spent the bulk of the school year mixing with teachers and classmates in person before being diverted online. Shady Hill plans a “soft” opening where about 20 percent of students are in the building just to practice new protocols.

Rivas will bolster her communication with families so she can ask them what their children need. With a fair number of students whose parents are first responders, she expects that staff will find a way to “hold kids accountable, and be generous and gentle.”

But as of late July, Rivas still didn’t know if her library would be open. “I’m hoping to get books to kids and teachers, but we don’t know what it will look like,” she says.

Either in-person or remote, Rivas expects to use books to help teachers and students begin difficult conversations about anxiety or social justice. “This will help our teachers talk more about race with a level of comfort,” she says. “I’ll probably contextualize the books more than I would normally, especially if they can’t come to the library.”

One way to meet students’ emotional needs is to connect them with research and literature that may help them express how they feel. One Florida private school librarian challenged her middle schoolers to study early pandemics and analyze how politicians, doctors, and businessmen handled the 1918 flu. This work helped demystify some of today’s rapidly changing news, she says, and gave students an outlet to understand the current situation better and discuss it with classmates.

|

A corner of the library at B. Everett Jordan Elementary School in Graham, NC, sits empty, awaiting its readers. The school starts the year with nine weeks of remote learning.Photo courtesy of Alamance-Burlington Schools |

Rethink typical tasks, take chances

EveryLibrary executive director John Chrastka is seeking to focus librarians with this simple advice: “Nothing’s changed about the mission of school librarianship; the mode of delivery has changed.”

Addressing equity, Bass says his district is speeding up its 1:1 plan by two years to ensure each student has both a device and an internet connection.

He says librarians should use this time to rethink the nature of what they do. “Librarians don’t have the same boundaries as classroom teachers,” he says. “They should provide authentic, meaningful experiences instead of trying to re-create physical classrooms.”

Davis agrees. “Librarians can be whatever the school needs them to be. They can coteach [and] provide enrichment and links.” Sometimes during the spring, she would pop into various classes’ Zoom calls just to say hello and offer students a read-aloud. She even held Zoom parties for kindergartners in her school, making sure to offer lots of imaginative activities, and sometimes silly dances.

Still, with so much focus on how children will handle the new school year, librarians have been deeply affected by all these changes, too. In the middle of reviewing her preparations, Timmins stopped and acknowledged, “I miss the kids. I miss them incredibly.”

Wayne D’Orio writes about education and equity.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

CRAIG SEASHOLES

Librarians unique role in education can be a significant support for students and staff scrambling with challenges of remote learning. Whether as guides to ensure successful navigation through online learning or as allies in the quiet explorations available through the right book at the right time...librarians are ready and able to deliver.

Posted : Sep 03, 2020 03:05