Antiracist Teaching: How Educators are Bringing New Lessons and Perspective to the Classroom

Over the past year across the country, educators have altered lesson plans and curricula to address racial injustice, historically and today.

|

Protesters in Louisville, KY, on June 2, 2020, following the deaths of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd.Photo by Darron Cummings/Associated Press |

On May 28, a crowd of more than 500 people gathered in downtown Louisville, KY, to protest the fatal shooting of city resident Breonna Taylor less than three months earlier. Coming only days after the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis, this protest was a harbinger of what was to come. Across the nation and throughout the summer, similar groups gathered and marched in small towns and large cities. The Black Lives Matter movement became mainstream in a flash.

For teachers and librarians across the country, this movement raised another question: How will we teach this in-the-moment history? For one educator in Louisville, the answer was easy—he would create his own curriculum.

“There was so much going on in the city, as a social studies teacher, I couldn’t back down from it,” says Andrew Danner, a high school teacher in the city’s Moore School.

Danner teamed with Meghan Hawkins, a teacher at Normal (IL) Community High School, to create lessons plans that include supporting questions, formative tasks, and a bevy of sources. One part of the lesson is an assessment in which students ask an adult if they participated in a protest and if they felt it made a difference. Another part of the lesson has students study photos from 2020 protests and state what they know about the event and what questions they would like answered.

Across the country, educators like Danner felt compelled to alter their programs to address racial injustice, today and historically, by changing curricula that have too often whitewashed, misrepresented, and avoided the racial violence and traumatic legacy of American slavery.

School leaders also put together antiracism committees and sought to include multiple viewpoints from students, staff, and community members. Textbook publisher Pearson issued editorial guidelines for its authors and reviewers to call attention to underrepresented ethnic groups and to avoid stereotypical descriptions of people of color.

One year later, how has this work played out in classrooms?

A cross section of students, teachers, and librarians say that real change is occurring in schools. From featuring books by traditionally underrepresented authors in libraries to adopting the New York Times’ 1619 Project curriculum, developed by the Pulitzer Center, to opening communication between students and staff, the social justice events of the summer of 2020 are altering schools.

But progress isn’t a straight line. Even in schools where the efforts of administrators and students seemed aligned, there have been bumps. At the Frank Sinatra School of the Arts in Queens, NY, principal Gideon Frankel pushed for the creation of an antiracism committee and posted four pages of antiracism resources, including a “starter kit” consisting of seven books.

Yet when students from the school took to social media to criticize staff for missteps such as failing to discuss the death of Breonna Taylor, the debate became “very charged,” says junior Devin Moss. “The students were calling out things that happened, and the school was upset about that,” Moss says.

Moss and her classmate Danielle Sanois are both on the school’s antiracism committee. Sanois says that some of the school’s curricula, including a prompt offered for Black History Month, “wasn’t reflecting the world we live in.”

But the group has seen many positive outcomes. Frankel helped the students create a four-hour conference on antiracism, including guest speakers who covered such topics as implicit bias. Students are hoping to make this an annual event. Moss and Sanois feel the effort at their school will be successful in the long term, in large part because of Frankel’s support and involvement.

Moss says when she speaks with other students across the country, many ask how they can convince their principals to support their efforts. At Sinatra, Frankel attends every antiracism meeting and pushes for student-led reform. “There’s been an incredible change in how we deal with things” because of this committee, Moss adds.

Progress amid pushback

At other schools, the discussion around incorporating antiracist curricula has been more charged, though momentum has been strong. It’s been less than two years since the creation of a curriculum for the 1619 Project, but it has already been adopted by schools in all 50 states, says Mark Schulte, education director for the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting. The curriculum follows the project’s assertion that American history began not in 1776 but 157 years earlier, when the first enslaved Africans arrived in Virginia. It includes lesson plans, reading guides, and even Quizlet flashcards related to the project’s essays. Chicago Public Schools issued copies of the project to every high school in its district.

But the opposition has been ferocious. Arkansas senator Tom Cotton called the project a “racially divisive, revisionist account of history” and tried unsuccessfully to prevent schools from using federal funds to teach the curriculum. Proposed bills in Arkansas, Iowa, and Mississippi echo Cotton’s complaints and call for schools to lose a proportion of state funding if they teach the curriculum. President Trump entered the fray, creating what he called “patriotic education,” before he left office. “We believe in patriotic education and strongly oppose the radical indoctrination of America’s youth,” he said in February. His 1776 curriculum was widely criticized by historians.

“The history of race in this country is a charged, painful topic,” Schulte says. The reading guides and lesson plans the Pulitzer Center created from the 1619 Project mirror states’ writing standards and are full of questions designed to spark debate about the project’s 18 essays. For instance, students studying Nikole Hannah-Jones’s essay “The Idea of America” are asked how laws, policies, and systems designed to enforce slavery influenced laws, policies, and systems after slavery was abolished. “If you look at our curriculum, you can see how many question marks are in there,” he says. “We ask questions and allow students to agree or disagree.”

“It’s painful to talk about slavery, reconciliation, and justice. We’ve got to stop sweeping this under the rug. This starts with telling the truth to our kids,” Schulte says. “I don’t think white people have anything to fear about the 1619 Project,” he says, referring to some claims that the guide is “indoctrination” that vilifies white people.

One criticism of antiracist curricula is it can simply instill a different way of thinking about things—that instead of delivering history from a white point of view, it’s from a Black/Indigenous point of view, says S.G. Grant, a professor of social studies education at Binghamton University. These lessons need to be inquiry-based, asking students questions and supplying sources, he adds. “You have to honor the fact [that students] may not agree with you.”

Danner’s curriculum was created in conjunction with C3 Teachers, an organization that aims to empower teachers dealing with the issues of college, career, and civic life. Grant is one of three leaders of the C3 Initiative. The curriculum asks students if there are similarities between historic and modern protests demanding civil rights and asks them to create a Venn diagram comparing those similarities and differences.

Although Moore School is located in the epicenter of the Louisville spring and summer protests, Danner found that students had a distorted view of what was happening in their own city.

|

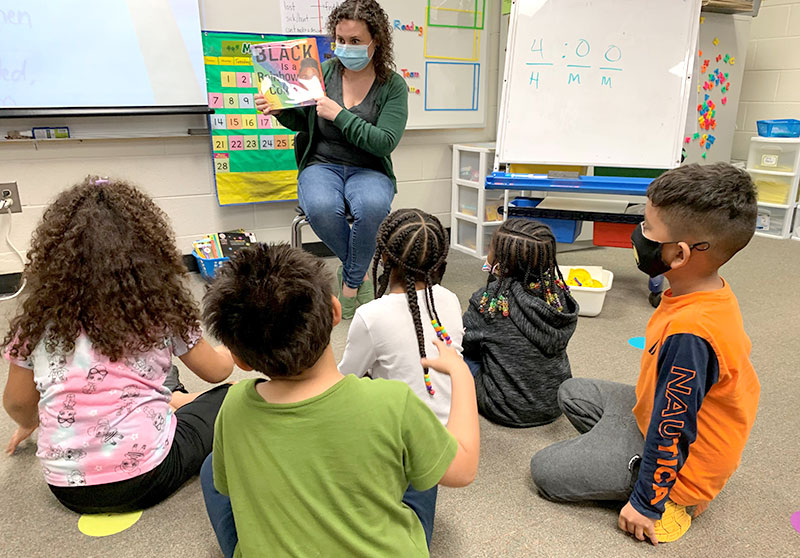

Nicole Duque, media specialist at McKendree Elementary School in Lawrenceville, GA, reads aloud with young students. |

“There was so much disinformation,” he says, and the overwhelming majority of students believed that the city’s protests were violent. Over four weeks of protests, there were only a handful of violent incidents, Danner adds.

Even though he and Hawkins wrote this curriculum just months before they were set to begin teaching it, Danner realized the still-evolving story would likely change. “We wrote it to be flexible,” he says. “Our goal is not to lead the students.”

Danner had his students consider the 2020 protests compared to other protests in our country’s history, asking them what, if anything, was new. “A lot of students weren’t used to a social studies class being taught like that. They struggled that we were asking them to argue” a point of view, as opposed to reciting facts and statistics.

He found that students’ conversations were much richer than the content of their writings, even though the lessons were taught remotely. “The students were pretty good at respecting each other’s opinions, but it was harder to be flexible with their own,” he says.

Like most schools, Moore School began the year with remote learning. “I’m excited to be able to do this in person,” he adds, thinking ahead to September. “It’ll be a lot easier to judge emotions and see their faces.”

The pandemic and the lack of in-person schooling has made it hard for some to initiate the full plans they envisioned back in September. Others have pointed out that while progress has been made, this work is difficult and there are miles to go.

“It is too soon to know” how antiracist curricula is going, says Melissa Pillot, the library and media specialist at the Forsyth School in St. Louis, MO. The preK-sixth grade–school hired a diversity consultant to work with staff and students. While Pillot was frustrated that past efforts seemed to consider only antibias training, she feels this new effort “has felt like progress.”

The biggest impacts at her school have come when teachers incorporated antiracism efforts specifically into curriculum, she says. A math teacher in fifth grade uses statistics to discuss racial issues, while a second grade social studies teacher now discusses redlining during a lesson on cities. Pillot helps both find appropriate resources. “These teachers have done training with the Learning for Justice Social Justice Standards, but our school has not adopted them as a universal guide,” she says.

While she mentions being frustrated at the pace of change, Pillot says, “The scaffolding works. I might not see the results of my lesson or a classroom lesson immediately, but when we are able to layer on top of each other’s work, I believe we are seeing the cumulative change in action.”

The highlight of the antiracism work at the Pike School in Andover, MA, is how it is “visible throughout the school community,” says Francesca Mellin, head librarian. Various groups including students, faculty, staff, and family members are meeting in discussion groups and town hall–style community meetings to address racist violence and antiracism work. The inclusion of both student voices and individual stories “shines a light on identity and how that helps point the way toward equity and justice,” says Mellin.

Leaning on inquiry teaching

Cicely Lewis, the Meadowcreek High School librarian who began the Read Woke campaign, says highlighting books by writers of color can help lead to fruitful classroom discussions. Her school, in Norcross, GA, has stopped reading To Kill a Mockingbird and replaced it with Nic Stone’s Dear Martin, she says, an example of a small curricular change that swaps one book for a newer one that covers many of today’s issues regarding race.

“It’s amazing to see people talking about these issues,” Lewis adds, saying she gets messages from educators every day discussing what their students are doing and saying because of these books. “I’ve seen a major, major, increase in the desire to provide these books to students.”

Nicole Duque, a media specialist at McKendree Elementary School in Gwinnett County (GA) Public Schools, tries to adapt antiracist teaching for younger students. She introduces conversations about race and racism with her fourth and fifth graders while reading Sharon M. Draper’s Blended aloud. The book is about a biracial girl with divorced parents, and it culminates with a racially biased incident.

The best inquiry teaching is rooted in open-ended questions, says Grant. Librarians can play a key role in helping to teach these lessons. “One of the biggest challenges to inquiry teaching is getting good sources,” he says. “Finding good, credible sources is really challenging. Librarians know far more about good sources” than most teachers.

The goal for this type of work doesn’t have to be complicated, Danner says. “I want to say, ‘Here’s where we are as a nation. How did we get here? What needs to change?’”

“We need to hear from different people with different perspectives,” says Sanois, from Sinatra. “The fear of being offensive or not agreeing shouldn’t stop us from having these conversations.”

Wayne D’Orio writes frequently about education and equity.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!