Dynamic Duo: Jessica Scheller and Andrea Ramirez, SLJ's Inaugural Librarian/Teacher Collaboration Award Winners

Scheller and Ramirez engage students while addressing the word gap at Eiland Elementary School in Houston, TX, and are the first recipients of the LIbrarian/Teacher Collaboration Award, sponsored by TLC.

SLJ ’S INAUGURAL LIBRARIAN/TEACHER

COLLABORATION AWARD WINNERS

|

Jessica Scheller, librarian (left) and Andrea Ramirez, art teacher, Eiland Elementary School, Klein ISD, HoustonPhotograph by Elizabeth Conley for SLJ |

|

RELATED ARTICLES An Assistant Librarian and Choral Director Take a Lyrical Approach to Black History A School Librarian and Fourth Grade Teacher Partner in Literacy and Outdoor Exploration |

In the 1990s, a famous study showed low-income children from birth to age 3 might hear 30 million fewer vocabulary words than high-income kids. This disparity could stunt their language skills and impact their early school experiences, according to the report.

When Andrea Ramirez, an art teacher at Eiland Elementary School in Houston, confronted this problem as a professional, she didn’t need to refer to studies. She could look back at her experience growing up as a Spanish speaker.

“My parents didn’t know English; they couldn’t sit down and read to me in English,” she says. As Ramirez was assigned homework in elementary school, her parents couldn’t sufficiently oversee her work. “They wouldn’t know if I read my book or not,” she says.

This firsthand knowledge led Ramirez to collaborate with Jessica Scheller, the school’s librarian, and create a project to help chip away at the word gap among pre-K–5 students.

More than 80 percent of Eiland’s students are Hispanic, and nearly 60 percent are English language learners. About 90 percent are from economically disadvantaged households.

The pair of educators immediately understood that they wanted to create projects that would include students and their families and lead to practicing language inside and outside the classroom.

Their inventive projects and successful collaborations earned Scheller and Ramirez the inaugural SLJ Librarian/Teacher Collaboration Award, created with support from TLC.

The award honors a pair of K–12 educators—a library professional and a teacher—for stellar achievement in engaging students toward fostering curious, lifetime learners.

Ramirez and Scheller made an impact as soon as they started working together. One of their first collaborations was a project that used Peter H. Reynolds’s book The Dot. Students read the book, which tells the story of a girl who feels she isn’t artistic, but gains confidence. Students created their own dots, sometimes working with their parents.

When families were invited to see the work showcased at school, the teachers realized that, for many, it was their first time taking part in a school program.

“It brought a sense of community, a collective experience,” says Scheller.

As they added to their vocabulary, students delighted in becoming “word collectors,” according to Eiland principal David Menendez. The two teachers have formed “a dynamic partnership that bridges our library and various media in the arts.”

The duo’s collaborations “engage students in ways that affect their learning by activating their creativity, ingenuity, and critical thinking simultaneously,” says Carol Gillingham, an intervention teacher at Eiland.

|

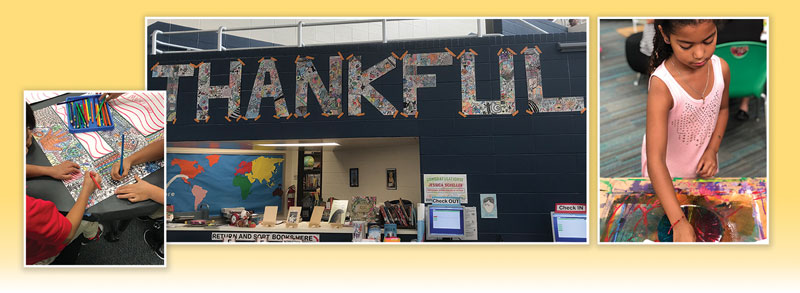

Eiland Elementary School students and their projectsCourtesy of Eiland Elementary School |

The Scheller-Ramirez partnership started the way many collaborations do within schools, with the librarian helping the teacher research a specific topic. Ramirez needed resources to help her teach students about the aurora borealis.

The librarian’s collection didn’t have many materials on that subject. A disappointed Scheller vowed not to let Ramirez down the next time she asked for help.

“If she asked for a book, I gave her 10 to 15,” Scheller says. “I would stalk her at staff meetings.”

Because the district’s library and art supply budgets combined are less than $5 per student, the pair needed to secure grants for larger projects, such as Read More Pictures. In this exercise, students were taught storytelling through wordless picture books. They created their own story panels using pen and ink, pastels, and watercolors, and then hung their work inside large six-foot wooden frames that were constructed by parents.

Another collaboration studied how characters develop over the course of a story. Concentrating on the school’s older students, the educators used Comic Life, a software program that helps students make their own comic panels.

Students learned vocabulary words by brainstorming various character traits, Scheller says.

The pair became so proficient in expanding students’ vocabulary that their principal asked them to focus on vocabulary related to testing to help prepare students for upcoming standardized exams. Students took words such as summarize, describe, and explain, and made posters with their own definitions. The posters were hung throughout the school.

In another project, the teachers sought to tap into students’ backgrounds by asking them to describe their family traditions.

Scheller offered her own tradition: “I told them that when the area gets hurricane warnings, my family plays Uno in the dark.”

Students highlighted their tradition on a piece of cloth, and their work was stitched together into a giant display that represented the entire school.

Seeing their artwork displayed throughout the school gave students confidence to try future projects, Ramirez says.

|

Ramirez and Scheller hold a patchwork cloth where students illustrated family traditions.Photograph by Elizabeth Conley for SLJ |

The art teacher led a project that showed students how stained-glass illustrations could be used to convey information. When students created their own panes using watercolors and markers, Scheller donated her overabundance of plastic book covers to use as materials.

Gillingham’s favorite Scheller-Ramirez collaboration involved the fourth and fifth graders’ study of biographies of famous people when they were children. Students discussed what information was included in the books and what questions they could ask to get that information.

Students then created biography projects by interviewing Eiland faculty and staff. They added photos of the subjects, used school iPads to post the work online, and created posters that hung throughout the school with the finished projects.

Pre-pandemic, Scheller says, “students would drag their parents [into the library] to see their artwork.”

“I witnessed students, parents, teachers, and others reading and discussing the biographies,” Gillingham wrote in a letter nominating the teachers for the collaboration award.

The biggest hurdle Ramirez and Scheller faced was proving to their school leaders that the library and art class could contribute to students’ learning, Scheller says. The leaders are convinced now.

“The library is a safe space for students, and art is a place students come to express themselves,” Scheller says. “Our work helped our administrators see that we could combine these things for a greater good.”

Wayne D’Orio is a journalist who writes about education.

|

|

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!