Shadow Books: Considering Enslavement and Its Legacy in Children’s Literature

Children’s literature is becoming more inclusive. But it has been a long, complicated road, and the journey is ongoing.

|

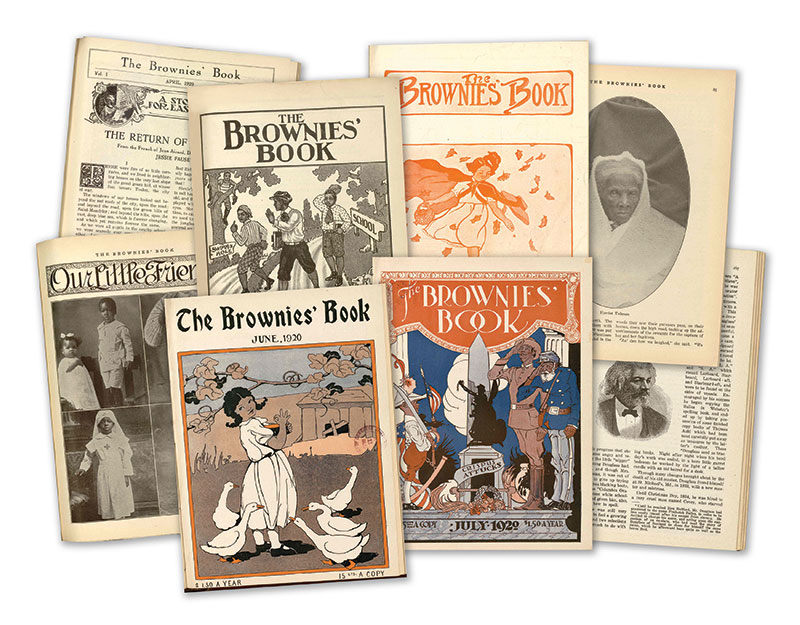

The Brownies’ Book, published in 1920–21 by W.E.B Du Bois and Jessie Fauset |

Children’s literature has been, historically, a site for the origin of ideas about race and racism in the United States. Since I was a child, I have wondered why Black children show up most often in certain genres of the fictions of childhood, and not in others. I grew weary of many of the Black children’s books I read when I was in school. It seemed that if we weren’t following the North Star to freedom or marching for civil rights, we were dodging bullets in the ghetto, or we were the Black best friend in the otherwise all-white landscapes of childhood and teen life. Although we’ve seen movement in recent years, my weariness has shown up during recent presentations as a cynical joke about “The Five Black Kids You Meet in Children’s Literature.” It’s quite telling that audiences almost always laugh. Knowingly.

Children’s literature has been, historically, a site for the origin of ideas about race and racism in the United States. Since I was a child, I have wondered why Black children show up most often in certain genres of the fictions of childhood, and not in others. I grew weary of many of the Black children’s books I read when I was in school. It seemed that if we weren’t following the North Star to freedom or marching for civil rights, we were dodging bullets in the ghetto, or we were the Black best friend in the otherwise all-white landscapes of childhood and teen life. Although we’ve seen movement in recent years, my weariness has shown up during recent presentations as a cynical joke about “The Five Black Kids You Meet in Children’s Literature.” It’s quite telling that audiences almost always laugh. Knowingly.

They’ve met those kids in books, too.

Children’s literature is becoming more inclusive. But it has been a long, complicated road, and the journey is ongoing. Black child readers, and their teachers, families, and communities, occupy a unique place when it comes to stories for children that deal with race. The collective trauma of enslavement—what literature scholar Saidiya Hartman has called the afterlife of slavery—has continuing implications for the descendants of enslaved people living today. That’s because slavery influences the way that Black people are perceived, more than 150 years after Emancipation. In The Souls of Black Folk, W.E.B. Du Bois notes the presence of Blackness as always already being a problem, in reality and imagination:

To the real question, How does it feel to be a problem?

I answer seldom a word.

Women, people of color, and other marginalized populations have always had to read ourselves into literary canons where we were absent.

We’ve always told our own stories. Black storytelling extend deep into our past, predating the Middle Passage and the Door of No Return, as poet and essayist Dionne Brand observes. After passing through the Door, African Americans have had to write ourselves into existence. Recently, journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones and author Renée Watson came up with another lyrical metaphor—Born on the Water, the title of their 2021 picture book in verse, derived from the 1619 Project. Black storytelling traditions have always existed in the shadows of the American story—and that includes in children’s books.

“The lost shadow book is the book that Blackness writes every day,” poet Kevin Young writes in The Grey Album. “The book that memory, time, accident, and the more active forms of oppression prevent from being read.”

I love this observation. Despite adversity, oppression, and the shadow books lost along the way, Black people have kept storying. “Storying,” Young writes, is how “Black writers have forged their own traditions, their own identities, even their own freedom.”

Prominent in the shadows cast by Black children’s literature is The Brownies’ Book, a periodical for Black children published in 1920–21 by Du Bois and Jessie Fauset, an editor and writer. Also published in 1921 was Willem van Loon’s The Story of Mankind, which includes the observation about enslaved Black Americans, “the Negroes were strong and could stand rough treatment.” It won the inaugural Newbery Medal the next year. Issues of The Brownies’ Book included stories, photographs, games, poetry, and information on current events; a goal was to dispel stereotypes of Black people and expand Black children’s literature. The Brownies’ Book was missing from mainstream shelves, but present in Black communities.

The restorying tradition

With The Brownies’ Book, Du Bois and Fauset were engaged in counter-storytelling, or what I call “restorying.” Later generations have restoried digital and virtual spaces, setting the web on fire with hashtag activism and TikTok takedowns, shaping our cultural discourse. Restorying is how we have survived.

But restorying in children’s literature is difficult, and genuine attempts to validate young Black readers in mainstream publishing have taken a long time. Nancy Larrick’s 1965 Saturday Review article “The All-White World of Children’s Books” is often cited as the first major examination of the depiction of African Americans in children’s literature, but the vital work of humanizing Black children in literature goes back much further. Black parents, educators, and clergy were noting and writing about problematic representations of Black people in children’s books as early as the mid-19th century.

Much of the impetus of African American children’s literature in the second half of the 20th century was reparative. Celebratory tales about Black Americans’ victories and achievements, despite collective trauma and monumental odds, appeared on shelves, promoting ideologies of racial uplift and encouraging young people to lead the race politically and socially toward American ideals of progress and individualism. But when our traumatic racial past is narrated within these civic aims, today’s students may feel alienated.

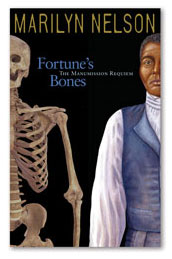

I’ve been interested in the role of slavery in children’s books for a long time, for all of these reasons. In 2007, as a doctoral student at the University of Michigan, I took a seminar with Michael Awkward on slavery and collective memory. Soon after, I picked up Connecticut poet laureate Marilyn Nelson’s award-winning illustrated chapbook for young readers, Fortune’s Bones: The Manumission Requiem. It’s one of my favorite historical children’s books. It is lyrical, lovely, and also can be quite challenging to teach.

Fortune’s Bones features the haunting, true account of an African American man enslaved by a physician in 18th-century Connecticut. When Fortune died in the 1790s, his family was denied burial rights, and for the next century, his skeleton was used to educate generations of physicians in New England. By the early 20th century, his identity was lost, and was only recovered during the civil rights movement. Debates over whether Fortune’s skeleton should remain on display at Connecticut’s Mattatuck Museum, or whether he should be buried, raged until September 2013, when his bones were finally laid to rest.

Fortune’s Bones features the haunting, true account of an African American man enslaved by a physician in 18th-century Connecticut. When Fortune died in the 1790s, his family was denied burial rights, and for the next century, his skeleton was used to educate generations of physicians in New England. By the early 20th century, his identity was lost, and was only recovered during the civil rights movement. Debates over whether Fortune’s skeleton should remain on display at Connecticut’s Mattatuck Museum, or whether he should be buried, raged until September 2013, when his bones were finally laid to rest.

Nelson ends the book with the poem, “Not My Bones.” Here’s an excerpt:

You can own someone’s body,

but the soul runs free

It roams the night sky’s

mute geometry.

You can murder hope, you can pound faith flat,

but like weeds and wildflowers, they grow right back.

For you are not your body,

you are not your body.

These are moving words, and Nelson is one of my favorite poets. But it can be challenging to teach when students are weary of what they consider “Black pain” stories. In the age of Black Lives Matter, stop-and-frisk, zero tolerance policies, and “the new Jim Crow” of mass incarceration, students of color and other marginalized kids might say: Yes, they are indeed their bodies. When young people’s experiences contradict those of people they read about in stories, they may feel disconnected from characters like Fortune. This disengagement inhibits what kids learn about slavery, but I’ve found that the truth of enslavement is difficult to convey in kids’ books.

The problem with portraying enslavement

My grad students and I have thought quite a bit about how to study image-text connections within slavery-themed picture books and children’s literature. Four questions have driven my research over the past decade:

• What kind of story is being told? What sorts of metanarratives, or “master” stories, do African American children’s books about slavery tell about Black history, culture, and life in the United States before 1865?

• Who is telling the story? Is the focalization external or internal? Is the narrator omniscient or first person?

• What is the role of slavery in the text? Is it the main theme, or relegated to the sidelines? How is the period of enslavement positioned?

• How are enslaved people represented? Are people in bondage positioned as human beings with agency, or are they stock characters who exist to prove a point? How are other Black people positioned?

We’ve found that the picture book genre pulls against authentic representation of slavery in the United States. So much about the institution simply can’t be depicted in books for young readers. Often, in an artistic effort to portray enslaved Black Americans as fully human, which is vital, the profound impact of enslavement is diminished on the page—and in a youngster’s imagination.

For instance, enslaved characters’ hardships are often barely mentioned or described. In picture books, historical context can be relegated to a preface or afterword. While these sections often describe the realities of enslavement, the stories children read often omit those realities. Benign portrayals of enslavement in the 19th century were powerful proslavery propaganda, and in the 21st century, we face backlash against children’s books that present what enslavement was really like.

Sadly, the noble goal of humanizing enslaved people through children’s books may send an unintended message: slavery wasn’t all that bad, something that one of my ninth grade students assured me many years ago. Yes, enslaved Black Americans experienced the full range of human emotions, but many children’s books about slavery provide limited perspectives of complex stories. Those early perceptions aren’t always corrected later in a child’s education, leading, I suspect, to disinformation about our nation’s past.

Wordless picture books

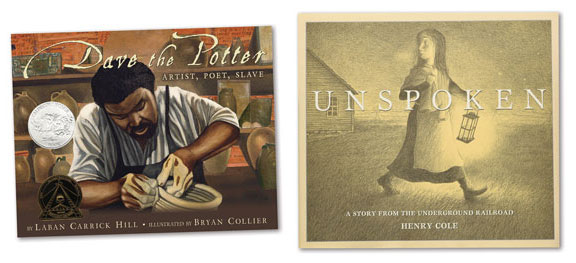

Picture books without words tell slavery stories as well. A case in point is Unspoken by Henry Cole. Kirkus Reviews positions the young white girl who is the unnamed protagonist as the only character with agency, asking, “What would you do if you had the chance to offer a person freedom?” These assumptions about readers—that they will relate to the white abolitionist, not the Black fugitive—are pervasive. Unspoken features no discernibly Black characters, yet this is a self-described “story from the Underground Railroad.” For a young reader to comprehend what is going on, they must rely upon an older child, teen, or adult chaperone knowledgeable about enslavement.

Children’s literature about slavery has generally featured characters who manage to escape enslavement, Black freedmen, and helpful white characters. Black characters are usually born free, manumitted, or imminently escaping enslavement. White characters are almost always helpful, good, and kind if they’re abolitionists—or misguided if they are engaged in the slave trade. Characters who are neither Black nor white are rare. Thus, in a book that claims to be about “the Underground Railroad,” Black characters—and by extension, Black child readers—are implied to be beside the point.

Creators don’t mean to imply that Black people are beside the point in books about slavery. The problem is in the genre itself.

Consider Dave the Potter. I highly recommend this Coretta Scott King Award–winning book by Laban Carrick Hill, illustrated by Bryan Collier. It features the life and work of early American poet and artist David Drake, born around 1800 on a South Carolina plantation, and freed after the Civil War as an elderly man. We see Drake at work, but not his face. The institution of enslavement itself in this book and others tends to be discussed in a distant, disconnected way. Like many enslaved people in children’s books, Drake does not express feelings of extreme pain, anger, or loss—emotions that we know that enslaved people felt—emotions that we know he felt. Terms such as master and slave are briefly explained, so young readers must make assumptions, have a certain level of prior knowledge about slavery.

I still believe that Dave the Potter is one of the best children’s books about enslavement ever created. Yet what will children take away from this and other books depicting enslaved Black people? Drake’s desire for emancipation, inscribed on many of his pots, is absent from the pictures, relegated to small text in the afterword. So is the fact that he was literate, unusual for enslaved people in South Carolina, as it was against the law. The fact that in one of his verses, he implies that his family was sold away, and he did not know their whereabouts, is also saved for the afterword. Ultimately, the focus on Drake’s artistic ability, instead of the tragedy of an artistic genius in chains, is a choice.

These choices protect young audiences from understanding the visceral lived experiences of those who lived and died in slavery. But to what effect? What happens when they learn the truth later, during history class? Will they accept the new information as true—or question it, like my former student?

I am wrestling with all of these questions as I begin to write my next book, The Shadow Book: Reading Slavery, Fugitivity, and Freedom in Children’s Books and Media . It pays homage to Black freedom fighters and scholars who have likened our place to shadows: Dr. Rudine Sims Bishop, Kevin Young. All the elders. All the ancestors. Mentors. And others. It rests on the life and legacy of Isabella Baumfree, known to history as Sojourner Truth, who famously “sold the Shadow to support the Substance.” Then there’s J.M. Barrie’s weird, colonialist obsession with shadows….

My current work with shadows is about all the leavings-behind, the wonderings, the sudden realization that my friend was right when she said in grad school “all roads in Black U.S. scholarship lead to slavery.” In order to reach for magic, in order to dream up the (Afro)future, we must reckon with the past.

We have thousands of shadow libraries, filled with diverse, decolonial, and emancipatory stories for young readers that we should have on our shelves, and don’t. Black creatives almost 200 years after Sojourner Truth’s time must “sell the shadow to support the substance.” The shadow that is sold (and told) is often stories about Black history that support, but rarely challenge, the American dream narrative.

Our fraught racial past has many implications for our world today, to say the least. Moreover, the story of U.S. slavery, and how that it has been narrated for children, is part of the challenge. The tales told by darkness, the shadows, those at the margins of our country are never completely erased or removed. They’re simply hidden in plain sight.

Ebony Elizabeth Thomas is the author of The Dark Fantastic: Race and the Imagination from Harry Potter to the Hunger Games.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!