UPDATE: High Schoolers Collaborate with Public Library Makerspace on Projects for Visually-Impaired Students

The partnership benefits the New Jersey students, who are learning accessible design and to create with empathy and imagination, as well as the blind and visually-impaired kids, who not only get to play the games but have a voice in the process.

|

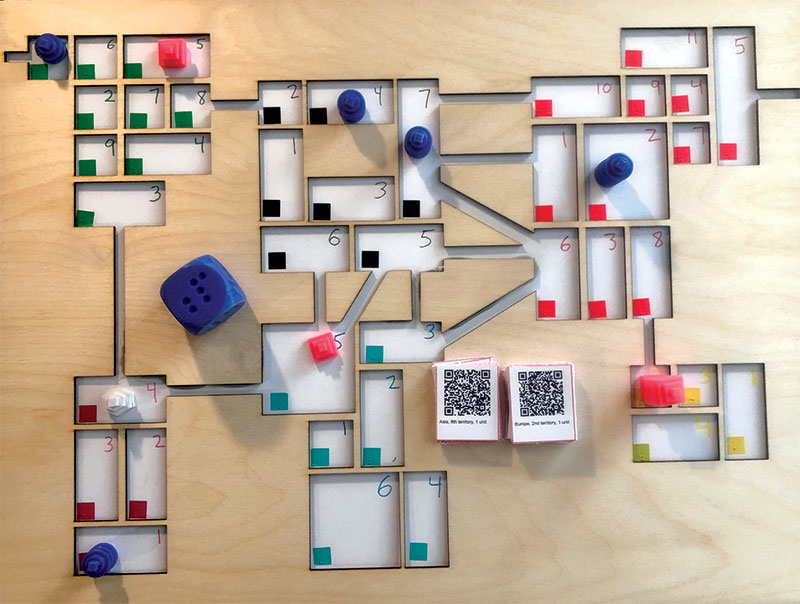

A prototype of the game Risk by the Mountain Lakes (NJ) High School students, working in collaboration with the town’s public library makerspace. |

Many libraries across the country created programs around the idea. In Mountain Lakes, the projects would not be shared with visually impaired and blind people but it was a day of making and challenging the typical way of thinking, a that forced these tweens to consider someone else’s challenges and create a very specific solution.

For Mountain Lakes Public Library Makerspace manager Ian Matty, the event was a good reason for one of his regular make-a-thons in the basement of the library and a way to help kids learn universal design and think about ways to design “for all.”

As an example, Matty put two Starbucks cards on the table. One had braille, one did not. Why wouldn’t all gift cards be printed with braille too, he asked. What else could be done to consider the challenges of the blind and visually prepared in daily life.

This project was specifically about finding a way to make children’s books accessible visually impaired and blind children, to enjoy the same way sighted children do.

The kids chose a book from a selection Matty pulled from the library collection and were tasked with creating a way to make the book tactile for a visually impaired person. Matty has worked with Build a Better Book for the last couple of years. He credits a conference with the organization a couple of years ago for teaching him a lot—including what he still needed to learn.

“I know more of what I don’t know, so I can step back and be more thoughtful,” he says.

PROJECT UPDATE:As the calendar year ends, Mountain Lakes Public Library Makerspace manager Ian Matty checked in to update SLJ on the Hex Game project. Pandemic distruptions did not stop these students.

|

The kids in attendance are focused on their projects and using many different resources in the makerspace.

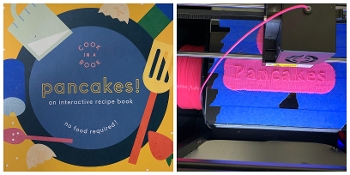

A couple of young makers used Tinkercad to create designs and soon the 3D printers hummed. One created a submarine for a book about how fast things go, another revealed layer on top of layer that would eventually be pancakes for a book called Pancakes.

One seventh grade girl chose a book about monsters as her inspiration. The book visually revealed more of the monster with each turn of the page. She took that idea and started drawing panels for a book about an owl. To make it tactile with felt and fabric, adding more to each page to reveal the owl at the end.

Her dad says she enjoys her time in the makerspace and she had a personal connection to this project, her uncle is blind. This day forced her to think concretely about how he interacts with books and what can be done to make that experience better for visually impaired children.

“She loves reading and today is about translating the love for reading into something you can touch,” he said.

Her dad, who also sends his son to maker events at the library, had an additional appreciation for Matty’s makerspace.

“You’re building something with your hands,” he said, comparing it to woodshop of years ago but “more complicated.”

Brandon Horn’s computer science curriculum at Mountain Lakes (NJ) High School (MLHS) always included a project. To get maximum buy-in from students, he would try to assign topics that interested them and would result in a product they would not only want to show to friends but could also use themselves. In the end, though, it was still just another academic exercise.

“A lot of projects in school are—I don’t want to say fake—they’re a bit contrived in the sense that they’re done for education purposes,” Horn says. “The closer you can get to a project that someone actually wants to use, the more motivated students are, the more interested that they are.”

Enter Ian Matty, the makerspace manager at Mountain Lakes Public Library (MLPL). Matty believed his makerspace could collaborate with the high school to give students “an amazing learning experience” through Build a Better Book, an organization that works with school and library makerspaces to design and create accessible picture books and graphics for the blind and visually impaired.

“It is making with meaning,” says Matty, who will be presenting a workshop, Build a Better Book: Empathy-Driven Design in School and Library Makerspaces, with members of the organization at the ISTE conference in Anaheim, CA, this summer.

Matty spoke with the MLHS principal, whose daughter had done projects in the MLPL makerspace. The principal went to Horn with the proposal. After discussing teaching philosophy and possible projects, Horn and Matty created a three-week Build a Better Book pilot program for a computer science class.

“The more authentic the projects, the better the course is,” says Horn. “This looked like a really cool way of doing authentic projects that could actually help people.”

That pilot was so well received, Matty and Horn began discussing possibilities for the 2019–20 school year. Since the partnership began, the interest and level of projects and collaboration have grown.

|

A St. Joseph’s student works with a marble maze made by MLHS students. |

With Matty as liaison, the collaboration now includes St. Joseph’s School for the Blind in Jersey City and students at a blind and visually-impaired games meetup in Sonoma County, CA.

Horn’s students learn to solve problems and design projects with real-world applications. They are creating games, mazes, and apps, which get used by the blind and visually impaired students, who offer feedback for improvement. The high schoolers then revise and rework. They are not only making the specific project better, they are learning accessible design. It goes beyond simply a school tech project.

“It is way more about exploring creativity with empathy and technology,” Matty says.

Neal McKenzie is the assistive technology specialist for visually impaired students for the Sonoma County Office of Education. He sees about 140 students throughout the county’s 40 school districts. He started the games meetup when he realized his students felt isolated and needed some of the same social opportunities as their sighted peers. Horn and Matty helped the MLHS students create a version of the game Risk for

McKenzie’s game group.

“To have something out of the box is huge for these guys,” says McKenzie. “They just want to be able to walk into a room and play the game. They don’t want to have to think about everything and modify it. They’re so used to doing that in everyday school situations and life.”

This collaboration has made McKenzie’s students part of the process.

“My real buy-in is when I get to relate back my students’ feedback,” he says. “I really like the idea they know there are people out there who will give them a voice.”

Students have learned that the more they use that voice, the more impact they can have.

“They’re excited about that,” McKenzie says. “I hope to continue to foster that and have more situations where that is the case.”

The Collaborative Hex Puzzle is the project this is furthest along. It is being sent out for feedback from different areas of the visually impaired community. For the blind and visually impaired, simply making something talk or tactile isn’t enough. Approaching a project the same way one would as a sighted user is not effective. The MLHS students have learned that quickly.

“At first, the kids were really just trying to replicate a tactile version of what they visually saw,” says McKenzie. “[Now], they are really thinking in a tactile sense would this even make sense. For someone who is accessing this not just purely visually, how would that be more effective? Now it’s starting to get into a deeper line of thinking that is pretty incredible to see.”

Getting kids to think differently is Matty’s goal—from the middle schoolers at a daylong make-a-thon in his makerspace (see box) to these computer science students working at a much more complex level in design and production.

The high schoolers have pushed past the original parameters and created more than games.

“One of the other cool projects was visual representations of neat things in math,” says Horn, who had one student who created a physical representation of the Seven Bridges of Königsberg problem. That project became part of an exhibit at the Boulder (CO) Public Library.

Create a Tactile Book Make-a-Thon

|

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Abby Smith

This is an awesome article about students solving real world problems. Incorporating relevant projects with STEAM subjects and creativity is a great for students. We have done similar things in the Ogden School District and our students have loved it.

Posted : Mar 05, 2020 07:33