Measuring SEL Competencies in a Summer Learning Program

A summer initiative allowed Denver Public Library to evaluate competencies such as relationship skills, engagement, and problem-solving, which are difficult to gauge with drop-in public library programming.

If you have ever high-fived a young library visitor, you’ve experienced the power of building relationships. Research shows that soft skills including bolstering self-esteem and interpersonal skills—collectively known as social and emotional learning (SEL)—are vital to life-long learning and academic success. SEL is described by the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) as “the process through which children and adults understand and manage emotions, set and achieve positive goals, feel and show empathy for others, establish and maintain positive relationships, and make responsible decisions.” Knowing how libraries support these skills is important to meet our goals as a profession and to communicate the value of libraries.

If you have ever high-fived a young library visitor, you’ve experienced the power of building relationships. Research shows that soft skills including bolstering self-esteem and interpersonal skills—collectively known as social and emotional learning (SEL)—are vital to life-long learning and academic success. SEL is described by the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) as “the process through which children and adults understand and manage emotions, set and achieve positive goals, feel and show empathy for others, establish and maintain positive relationships, and make responsible decisions.” Knowing how libraries support these skills is important to meet our goals as a profession and to communicate the value of libraries.

At Denver Public Library (DPL), we knew anecdotally that we were positively affecting SEL, but wanted to find a way to measure it. In 2017, DPL began shifting from a summer reading program to a summer learning program called Summer of Adventure. That initiative focuses on building relationships and facilitating social and emotional learning in addition to addressing summer learning loss.

This was an opportunity to focus on measuring outcomes, rather than outputs like registration and attendance numbers. Outcomes are the impacts that a program has on participants, like increasing academic or social skills. With the support of the library’s leadership, we launched a pilot project to evaluate Summer of Adventure outcomes. Our team consisted of two DPL librarians and a research analyst from Colorado State Library’s Library Research Service.

We hope that learning about our project will increase your SEL knowledge and inspire you to try measuring SEL in practical, helpful ways.

Context

Summer of Adventure is DPL’s system-wide summer program for babies, children, and teens. Youth read, explore, attend programs, and earn prizes. Each DPL location facilitates activities like art and STEM programs, storytime, and performances. In 2017, through a grant, the library partnered with Denver Public Schools’ Summer Academy to offer STEM and craft activities at an elementary school for four weeks.

Summer Academy (pictured) gave us the opportunity to measure SEL competencies such as relationship skills, engagement, and problem-solving with a consistent group of youth—not usually possible with drop-in public library programming. Our evaluation focused on participants entering first, second, and third grades in fall 2017.

The outcome goal for the program was: “After Summer Academy, participants will gain or enhance their social and emotional skills.” We knew we would not likely see measurable change in SEL skills during the month-long program, so our evaluation question was: “What social and emotional skills do youth participants currently have?” We wanted to know what skills youth need to build and learn more about how different types of programming encourage positive SEL behaviors.

We used the Backwards Design curriculum design process, created by Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe, to design our evaluation. You start with the desired outcome, then determine how you will know if the outcome was achieved, and, last, design activities to support the outcome. The key is to design the activities last, not first.

The tricky part about our project was determining how to measure behavior. Based on research methods in education, SEL, and the social sciences, we decided that observations were the best way to measure SEL behaviors. We also asked youth directly about their experience using: 1) smiley face surveys about how fun and hard an activity was and 2) a final reflection activity about what they liked the most and least about Summer Academy.

Unfortunately, neither the smiley face surveys nor the final reflection projects told us much about SEL behaviors. On the survey, kids circled that they had a lot of fun during activities when we observed clear frustration and disengagement. On the final reflection projects, they were not specific about their experience—they drew hearts and said they made friends. We could not interpret this data in a systematic way to make conclusions about SEL.

We concluded that these two assessments were not developmentally appropriate because the participants were too young to give specific or non-positive feedback. We recommend against using these strategies with this age group or younger children. Our observational data became our primary focus.

Conducting observations

We observed students for four days during the month-long program. Because of the detail we wanted to capture, our evaluation team conducted the observations, rather than asking the library staff facilitating the program to both lead and observe. Each observer watched several students during an activity and used a guide to focus on SEL behaviors, writing down everything they saw. To minimize the impact of observer bias, multiple people observed each participant during each activity.

Beforehand, we collected a signed informed consent form from caregivers. The form, shared in English and Spanish, explained the project and requested written permission to observe their child. Using an informed consent process is a best practice for any research project, in particular one with a vulnerable population like children. We received 19 signed permission forms. Due to inconsistent attendance, we collected observational data for 17 participants.

Analyze & evaluate

Our next challenge was to transform our many pages of notes into a product that could be interpreted and used to make decisions. We developed a coding scheme, assigning a label or “code” to categorize data.

The SEL observation rubric/coding scheme we developed addressed three areas of behavior:

● Self-management

● Relationship skills

● Problem-solving

Our scheme links observed behaviors to the CASEL core competencies. Each category includes behaviors that positively demonstrate SEL (positive), indicate a need for SEL skill development (negative), or vary too much to interpret consistently without knowing the youth’s intention (neutral). For example, the category of self-management includes behaviors such as listening and being on-task (positive), distraction and not being responsive to directions (negative), and interrupting (neutral). Interrupting is an example of behavior that is hard to interpret since it can happen because a child is having trouble with self-control, or because they are excited and engaged. We did not evaluate the youth as positive or negative, but whether each behavior demonstrated an SEL competency.

We assigned a code to each behavior in our notes using the coding scheme. For example, an observation note during a tree art project was “participant painted a branch on their tree after the teacher demonstrated how to do it.” Since this behavior demonstrated listening and being on task, we coded the behavior as positive self-management.

We then grouped the data to identify patterns and address our questions: What SEL skills did participants demonstrate during library programs? Did participants behave differently during different activities?

Results

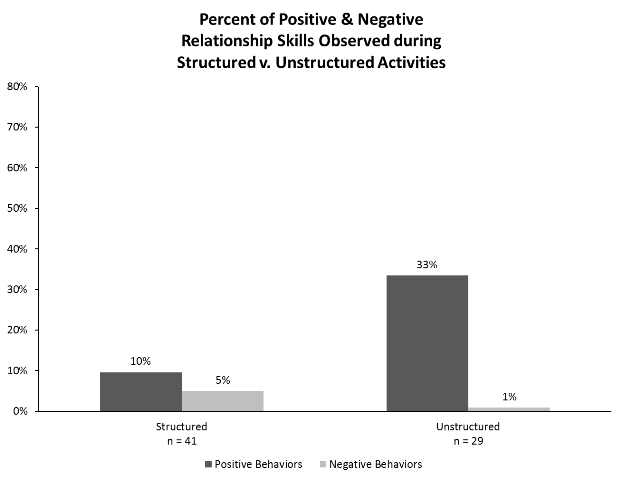

A key finding was that relationship building occurred more during unstructured rather than structured activities. During unstructured activities, like collaborative LEGO building, we observed more positive relationship skills (chatting, sharing, being kind). Some applications of these results are for libraries to offer activities with less structure that encourage collaboration, like games, and to intentionally include collaboration in structured activities, to increase relationship-building opportunities.

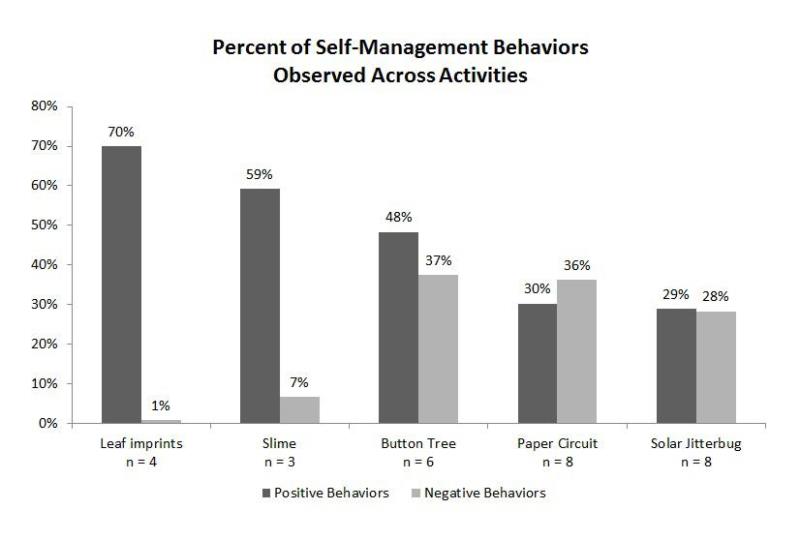

The youth participants showed the most positive self-management during moderately challenging activities allowing many ways to complete the product, such as making slime and using leaves to make imprints in clay. We saw more positive self-management behaviors (like engagement) during these activities. Two of the more challenging and structured activities were making a solar jitterbug and a paper circuit greeting card. These involved creating electrical circuits, which required following detailed written instructions, and advanced fine motor skills. Many participants struggled with self-management (like distraction) during these challenging activities.

This observation aligns with the concept of the “zone of proximal development,” developed by psychologist Lev Vygotsky. It refers to what learners are able to do with appropriate guidance and scaffolding, but cannot yet do independently. Our findings suggest that when activities are challenging but within children’s zone of proximal development, participants tend to be more successful at self-management.

It is important to note that this pilot project had limitations, and our findings cannot be generalized. Our sample size was small—17 participants—and often even fewer completed the same activity at the same time. It is also unclear if our sample was representative. Other factors may have influenced our results; for example, very hot days may have impacted self-management behaviors.

Project impact

Prior to this project, DPL had devoted significant time and energy to summer programming without much data about its impact. Library staff used our information to help make strategic decisions about future programs and communicate with external stakeholders and funders about the program’s value.

DPL continues to adjust the program to better support SEL, intrinsic motivation, and life-long learning. The library provides training to help staff support SEL. Youth services leaders recently shared with us that the project completely changed how they think about evaluation for the better. They now always consider the outcome they are trying to accomplish when planning programs. Additionally, DPL formed an internal evaluation task force to support staff in developing and conducting effective assessments.

We hope that sharing our rubric as a free resource makes it easier for other libraries to support and evaluate SEL. Here are some ideas for how libraries could adapt this tool to assess SEL.

● Pick a teacher whose teaching style interests you or whose students are engaged. Ask their permission to observe in their classroom for 30 minutes. Pick one area of the rubric, like relationship building, to focus on while you observe. During what activities do students seem to use this skill the most? Is there anything the teacher does to support them? How might students benefit from additional skill building?

● Try offering collaborative, team-based activities in your library. Roam around to observe different groups, and notice where conflict develops and where they get stuck. Do these connect to specific social and emotional skills? If so, try setting an age-appropriate SEL focus for the day, such as “Today, focus on being kind to your teammates, like saying please and thank you and giving compliments on each other’s effort.” Do you notice changes in behavior?

● Review the positive behaviors identified on our rubric. Try casually noticing students’ SEL skills for a week or two when they are in the library. Based on that, what SEL skills would you most like to encourage in your library? Make a display or bulletin board based around one area, maybe including books with characters demonstrating positive behaviors. Students could participate by suggesting books to add to the display that address a specific SEL behavior. See if student behavior seems to change with different displays.

● Ask a teaching colleague to observe student behavior while you facilitate an activity. Give them a copy of the observational rubric to guide their thinking and a specific area to focus on, like self-management. Afterward, have a 5-20 minute conversation about what they noticed.

● If students use your library both supervised and unsupervised, notice if they excel at or struggle with specific SEL skills depending on if they are supervised or not.

● Keep an SEL reflection journal. Pick an area of SEL to focus on. After you interact with a class or group, write a few sentences about the interaction. What went well? What didn’t? What are you curious about?

Check with your supervisor or principal about your institution’s research policies before starting any research project. With children, it is particularly important to make sure that your efforts are aligned with ethical research guidelines. Don’t record any identifying information about individual children without written permission from their guardians. A conversation with stakeholders about goals and procedures at the start of even a small project is an opportunity to explain the importance of SEL skills, build support, and generate enthusiasm.

More information about SEL :

● Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL)

● “The Economic Value of Social and Emotional Learning” ( Journal of Benefit-Cost Analysis)

● “The Psychological Approach to Educating Kids” (The Atlantic)

● Social and Emotional Learning (Princeton University’s The Future of Children)

Katie Fox is a research analyst in the Library Research Service Unit at the Colorado State Library, where she delights in exploring messy evaluation questions. Hillary Estner is the senior librarian at the Ross-Cherry Creek Branch of the Denver Public Library. Erin McLean is an education and outreach librarian with a taste for culinary-themed collections and well-designed spreadsheets.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!