Russia and Children’s Literature: A Storied History

If you haven’t been living under a large comfortable rock for the last year or so then you might have noticed that Russia has been in the news quite a bit. If you have been under a large comfortable rock, is there room down there for me too?

It’s funny but with all the talk of Soviets, spies, intelligence reports, counterintelligence reports, and the like it wasn’t until my husband mention Tintin the other night that it reminded to me that our current state of political affairs is reflected time and again in our children’s literature. The aforementioned husband has been reading our daughter down with Tintin and in the course of it mentioned that there were two particularly controversial Tintin’s out there. Tintin in the Congo was already well known to me, but I was unfamiliar with Tintin in the Land of the Soviets. In it Tintin is sent to Soviet Russia to report on Stalin’s government. It was very crude (Herge’s first work) and was basically just a framework for him to allow his main character to beat the crap out of some Bolsheviks. It is often considered one of the worst Tintins.

It’s funny but with all the talk of Soviets, spies, intelligence reports, counterintelligence reports, and the like it wasn’t until my husband mention Tintin the other night that it reminded to me that our current state of political affairs is reflected time and again in our children’s literature. The aforementioned husband has been reading our daughter down with Tintin and in the course of it mentioned that there were two particularly controversial Tintin’s out there. Tintin in the Congo was already well known to me, but I was unfamiliar with Tintin in the Land of the Soviets. In it Tintin is sent to Soviet Russia to report on Stalin’s government. It was very crude (Herge’s first work) and was basically just a framework for him to allow his main character to beat the crap out of some Bolsheviks. It is often considered one of the worst Tintins.

Now Tintin is not always considered “children’s literature” even though that’s precisely what it is. But if we want to talk about pure unadulterated books for kids, there’s plenty of Soviet drama to draw from. This is, strictly speaking, Phil Nel’s territory more than my own, but I shall endeavor to explain as best I can some of the highlights. The relationship between Russia and American in U.S. children’s literature separates neatly into the following sections:

- Russian Modernism Children’s Books of the 1920s

- The Communist Movement in America

- The Red Scare

- Eloise

In that order, no less.

So let’s talk modernism. In 2012 I was working at New York Public Library and helping scholar Leonard Marcus track down some of the more interesting gems in our collections. Leonard had been charged with putting together an exhibit of NYPL’s children’s literature treasures and was taking the job very seriously. On this particular day Leonard wanted to look at the library’s collection of Russian children’s literature. This was an aspect of history of which I was entirely unaware. My world history knowledge was pretty much relegated to American history, so I had no idea what these books were. Since that time I’ve had the chance to read M.T. Anderson’s remarkable Symphony for the City of the Dead which goes into a great deal of depth relating the artistic flourishes of Russia in the 1920s. In the bowels of NYPL Leonard pulled out book after book after book, all of them original to Russia, all of them meticulously collected by NYPL’s children’s librarians back in the day. Once upon a time New York Public Library prided itself on its world languages collection. I don’t know how they managed to get quite so many Russian picture books, but what I can attest is that the art in them was stunning. The modern design was unlike anything I’d encountered before. It looked something like this:

So let’s talk modernism. In 2012 I was working at New York Public Library and helping scholar Leonard Marcus track down some of the more interesting gems in our collections. Leonard had been charged with putting together an exhibit of NYPL’s children’s literature treasures and was taking the job very seriously. On this particular day Leonard wanted to look at the library’s collection of Russian children’s literature. This was an aspect of history of which I was entirely unaware. My world history knowledge was pretty much relegated to American history, so I had no idea what these books were. Since that time I’ve had the chance to read M.T. Anderson’s remarkable Symphony for the City of the Dead which goes into a great deal of depth relating the artistic flourishes of Russia in the 1920s. In the bowels of NYPL Leonard pulled out book after book after book, all of them original to Russia, all of them meticulously collected by NYPL’s children’s librarians back in the day. Once upon a time New York Public Library prided itself on its world languages collection. I don’t know how they managed to get quite so many Russian picture books, but what I can attest is that the art in them was stunning. The modern design was unlike anything I’d encountered before. It looked something like this:

“Stunning”, by the way, is just the word I’d use for the recent New York Review Children’s Collection release of the book The Fire Horse: Children’s Poems by Mayakovsky + Mandelstam + Kharms, translated by Eugene Ostashevsky. When it arrived in my mail I wasn’t quite certain what to expect. I took the subtitle at its word. Poems, eh? Russian children’s poems? Never seen that one before. Turns out, the subtitle is a bit of a misnomer. Rather than a collection of poems the book contains three children’s books, originally published in Russian in the 20s. There’s a Philip Pullman blurb in the accompanying letter from the publisher saying, “The early Soviet period was a miraculously rich time for children’s books and their illustrations.” This is borne out by the tales inside. The first is a 1928 title called “The Fire-Horse” where a boy acquires an appreciation for everyday workers as each one helps to make him a part of a toy horse to ride. The 1928 “Two Trams” is an odd, dreamlike tale of anthropomorphic tramcars named Click and Zam who work the tracks of Leningrad. Finally, there’s the 1930 story “Play”, my personal favorite, with a concept that could be published easily today. Three boys play pretend, one as a car, one as a plane, and one as a ship. The fates of the authors of these stories are almost as engrossing (for grown-ups) as the tales themselves. Daniil Kharms was an absurdist poet and founder of the avant-garde collective OBEIRU. He died at the age of 37. Vladimir Mayakovsky was part of the Futurist movement. Osip Mandelstam wrote a poem called “Stalin Epigram” and died in a transit camp in 1938.

“Stunning”, by the way, is just the word I’d use for the recent New York Review Children’s Collection release of the book The Fire Horse: Children’s Poems by Mayakovsky + Mandelstam + Kharms, translated by Eugene Ostashevsky. When it arrived in my mail I wasn’t quite certain what to expect. I took the subtitle at its word. Poems, eh? Russian children’s poems? Never seen that one before. Turns out, the subtitle is a bit of a misnomer. Rather than a collection of poems the book contains three children’s books, originally published in Russian in the 20s. There’s a Philip Pullman blurb in the accompanying letter from the publisher saying, “The early Soviet period was a miraculously rich time for children’s books and their illustrations.” This is borne out by the tales inside. The first is a 1928 title called “The Fire-Horse” where a boy acquires an appreciation for everyday workers as each one helps to make him a part of a toy horse to ride. The 1928 “Two Trams” is an odd, dreamlike tale of anthropomorphic tramcars named Click and Zam who work the tracks of Leningrad. Finally, there’s the 1930 story “Play”, my personal favorite, with a concept that could be published easily today. Three boys play pretend, one as a car, one as a plane, and one as a ship. The fates of the authors of these stories are almost as engrossing (for grown-ups) as the tales themselves. Daniil Kharms was an absurdist poet and founder of the avant-garde collective OBEIRU. He died at the age of 37. Vladimir Mayakovsky was part of the Futurist movement. Osip Mandelstam wrote a poem called “Stalin Epigram” and died in a transit camp in 1938.

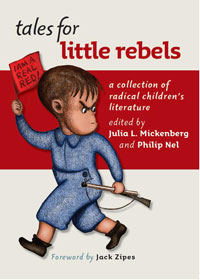

So Soviet Russia “saw a brief golden age in children’s books, one that predated equivalent periods of creativity and progress in Western countries by decades.” Then Stalin tightened his hold and things changed severely. Meanwhile, over in America, after the end of WWII, many was the children’s author that flirted or joined with the Socialist and/or Communist parties. This is all beautifully documented in Phil Nel’s Tales for Little Rebels: A Collection of Radical Children’s Literature which he edited with Julia L. Mickenberg. In that book you’ll find such gems as an excerpt from “The Socialist Primer: A Book of First Lessons for the Little Ones in Words of One Syllable” by Nicholas Klein circa 1908 and blacklisted author/illustrator William Gropper’s “The Little Tailor” (1955) amongst many others. He goes into even further detail about, specifically, Crockett Johnson and Ruth Krauss in his seminal Crockett Johnson and Ruth Krauss: How an Unlikely Couple Found Love, Dodged the FBI, and Transformed Children’s Literature. Johnson for a time hoped for peace between the U.S. and Russia after WWII. As Phil writes:

So Soviet Russia “saw a brief golden age in children’s books, one that predated equivalent periods of creativity and progress in Western countries by decades.” Then Stalin tightened his hold and things changed severely. Meanwhile, over in America, after the end of WWII, many was the children’s author that flirted or joined with the Socialist and/or Communist parties. This is all beautifully documented in Phil Nel’s Tales for Little Rebels: A Collection of Radical Children’s Literature which he edited with Julia L. Mickenberg. In that book you’ll find such gems as an excerpt from “The Socialist Primer: A Book of First Lessons for the Little Ones in Words of One Syllable” by Nicholas Klein circa 1908 and blacklisted author/illustrator William Gropper’s “The Little Tailor” (1955) amongst many others. He goes into even further detail about, specifically, Crockett Johnson and Ruth Krauss in his seminal Crockett Johnson and Ruth Krauss: How an Unlikely Couple Found Love, Dodged the FBI, and Transformed Children’s Literature. Johnson for a time hoped for peace between the U.S. and Russia after WWII. As Phil writes:

“On 14 May, he donated one hundred dollars and attended a New Haven ‘Peace and Security Rally’ sponsored by the Communist Party of Connecticut.”

As a result, he was watched and scrutinized for years.

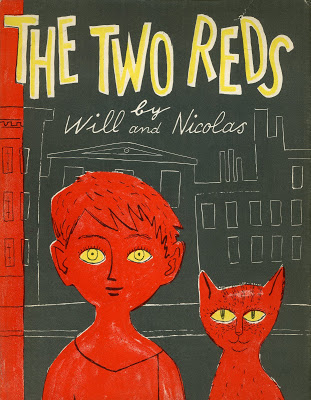

The Red Scare, once it started in earnest in the States, spread like wildfire and even children’s books were not immune. In my book Wild Things: Acts of Mischief in Children’s Literature, which I co-wrote with Julie Danielson and Peter Sieruta, we write at length about how an innocent little picture book came under serious fire. While blacklisted adult authors like Louis Untermeyer and Langston Hughes started writing for kids, William Lipkind and Nicholas Mordvinoff were facing an uproar of a different kind. Mordvinoff had left Russia as a kid and arrived in NYC in 1946. He met Lipkind through the man’s wife (who worked for NYPL, by the way). On a lark they collaborated on a picture book about a boy and his cat. The boy was named Red and the cat shared that name. The title of the book? The Two Reds. And maybe it could have all gone swimmingly, had a window dresser at FAO Schwarz not caught wind of the book and made a colorful display for it. People were aghast. A book called “The Two Reds” written by a Russian had gotten published in America?!? How did this even happen? The Two Reds was not pulled from publication but it was banned in Boston. But for many the book signified an act of bravery. As Fritz Eichenberg said, “It takes great courage, for reasons too numerous and obvious to mention, to name a children’s book The Two Reds.” And for the record, that window dresser may have been Maurice Sendak. That’s the story, anyway. The world may never know.

The Red Scare, once it started in earnest in the States, spread like wildfire and even children’s books were not immune. In my book Wild Things: Acts of Mischief in Children’s Literature, which I co-wrote with Julie Danielson and Peter Sieruta, we write at length about how an innocent little picture book came under serious fire. While blacklisted adult authors like Louis Untermeyer and Langston Hughes started writing for kids, William Lipkind and Nicholas Mordvinoff were facing an uproar of a different kind. Mordvinoff had left Russia as a kid and arrived in NYC in 1946. He met Lipkind through the man’s wife (who worked for NYPL, by the way). On a lark they collaborated on a picture book about a boy and his cat. The boy was named Red and the cat shared that name. The title of the book? The Two Reds. And maybe it could have all gone swimmingly, had a window dresser at FAO Schwarz not caught wind of the book and made a colorful display for it. People were aghast. A book called “The Two Reds” written by a Russian had gotten published in America?!? How did this even happen? The Two Reds was not pulled from publication but it was banned in Boston. But for many the book signified an act of bravery. As Fritz Eichenberg said, “It takes great courage, for reasons too numerous and obvious to mention, to name a children’s book The Two Reds.” And for the record, that window dresser may have been Maurice Sendak. That’s the story, anyway. The world may never know.

We’ve talked about books that were perceived to be dangerously subversive in America. I think it might behoove us to look at a book that flipped the other way. The deeply anti-Communist Eloise in Moscow rounds out our post today, and what a strange book that is. I think it’s safe to say that of all the Eloise books, this one is the weirdest. First off, the very premise is a bit flawed. How did Eloise even GET in Moscow? That’s left a bit hazy. Her mom sent for her, but her mom’s not there so it’s just Eloise, Nanny, a guide, and a government tail. As with any Eloise book there are lots of inside jokes for the adult readers, but these are so specific to the times that I’m afraid I probably only got about half of them. I would love to hear Hilary Knight speak some time about doing this book. What on earth could the impetus have been on Kay Thompson’s part? My theory: She probably did a really good Russian accent and wanted a book made that could play on that. Hey, it’s as likely as anything else.

We’ve talked about books that were perceived to be dangerously subversive in America. I think it might behoove us to look at a book that flipped the other way. The deeply anti-Communist Eloise in Moscow rounds out our post today, and what a strange book that is. I think it’s safe to say that of all the Eloise books, this one is the weirdest. First off, the very premise is a bit flawed. How did Eloise even GET in Moscow? That’s left a bit hazy. Her mom sent for her, but her mom’s not there so it’s just Eloise, Nanny, a guide, and a government tail. As with any Eloise book there are lots of inside jokes for the adult readers, but these are so specific to the times that I’m afraid I probably only got about half of them. I would love to hear Hilary Knight speak some time about doing this book. What on earth could the impetus have been on Kay Thompson’s part? My theory: She probably did a really good Russian accent and wanted a book made that could play on that. Hey, it’s as likely as anything else.

Fastforward now, with me, to 2017. Trump is in the White House. A special prosecutor has been named to lead an investigation. And Russian children’s books are few and far between on American shelves. Translated works for kids are hard to get in Americans’ hands in the first place, but I must say that I’ve not seen a contemporary Russian book here in a very long time. Russian authors and illustrators, maybe. Books? Not so much. Still, even as we watch what happens in D.C., it’s important to look at how all of this went down before. Russia has been a consistent source of children’s books and controversy, sometimes at the same time. Let’s look at their history and our history and learn.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!