Get the Most Out of Zoom, Nearpod, Biblionasium, and Other Tools While Teaching Remotely

Innovative ways to use technology to keep students engaged and on track during the pandemic.

|

Screen images via (from left): Amanda Jones; Nearpod; Desmos; K.C. Boyd (using Word It Out). |

What’s the Zoom breakout room balance? Are student cameras on? How many questions are in the chat? Such now-routine questions illustrate education’s rapid-fire transformation since the pandemic started. Teaching in libraries and classrooms looks different, whether educators are talking to a grid of students’ faces on-screen or a half-filled classroom with students sitting behind Plexiglas barriers, six feet apart.

Regardless of how school is being conducted, librarians have been striving to innovate in order to reach all students. What tech and teaching methods best keep students engaged and on track?

“I think all teachers are really experiencing challenges with how to meet the needs of various learners,” says Todd Burleson, fifth and sixth grade librarian at the Skokie School in Winnetka, IL, and 2016 SLJ School Librarian of the Year. “I would be honest and say that I think we’re really struggling with this.”

This academic year, reaching students has been a top concern. To do so, innovative librarians are experimenting with practices including applying online grouping strategies to live environments, staying flexible with “camera on” policies, and hosting virtual field trips and social events to keep students connected.

|

Working virtually in small groups gives students an “authentic audience,” says Oregon library and instructional technology teacher Colette Cassinelli.Photo courtesy of Colette Cassinelli |

The camera question

Online learning has been around for years, of course. University environments and secondary education have found success in virtual learning modules and hybrid courses, making the most of the flexibility to engage various types of learners. But many K–12 educators felt at sea with the virtual shift. “Some faculty never experienced an online learning environment, so it’s hard for them to even think about what that can look like,” says Ingrid Sabogal, middle school ethics and technology coordinator at Ethical Culture Fieldston School in New York City.

Sabogal was one of the staff tasked with guiding teachers and students as the private school transitioned to online learning. Her inbox was flooded with requests. “It was back-to-back emails of ‘Can I use this app?’ and ‘I’m trying to use this app,’” says Sabogal. “I was like, ‘Whoa, take a pause.’”

Before ushering in a tool or technology, Sabogal has teachers assess whether it will actually enhance the lesson. The school’s rigorous screening process for new education software and technology involves evaluating it for user privacy and security and thinking about how it will be received by students. The use of computer cameras was a big issue.

“All the teachers want the camera on, because they want to see their kids. They’re used to gauging engagement by viewing a student,” she says. “But we all know developmentally adolescents go through so many things and the camera is something that impacts them.”

While giving presentations in class, teachers would see a trickle effect: One student turns off their camera, and then they all start to follow suit, she says. Sabogal encourages faculty to be understanding of the reasons a student may want to be off-camera, such as peer pressure, home environments, or internet bandwidth. “Do you really prefer to have their face, or would you rather have them with their camera off and really engage in activities?” she says.

Big impact in small groups

Sabogal and her team have found more success engaging with students with small group projects. Teachers use their synchronous class time for small group discussions and activities and asynchronous time for lecture slides, reading assignments, and homework that can be completed individually at any pace.

Colette Cassinelli, library and instructional technology teacher at Sunset High School and the Arts and Communication Magnet Academy in Beaverton, OR, uses an assortment of tools to boost collaboration in small groups, online and in person. One is a digital book crafter called Book Creator that provides a shell of an ebook, where students can compile research on a unit or tell a story. Her middle school language arts students create their own graphic novels based on reading assignments, and AP English classes come up with their own interpretations of Beowulf. Cassinelli is brainstorming ways to use Book Creator to help students learn how the scientific process and peer review publishing work.

“Kids get to know each other in these small groups,” she says. “It’s also an authentic audience. They’re doing this for somebody else to watch or to read.”

Burleson uses Zoom breakout rooms to bring out more participation in smaller groups. At partially in-person classes, with students six feet apart and behind plastic guards at their desks, it’s difficult for the teacher and classmates to collaborate, he finds. “So we’re applying some of the very same things we’re using in our virtual classes to our actual classes to enable students to share and chat alongside one another,” he says. “We’re using Zoom to have small groups meet with headphones on so that they can all hear each other from across the room.”

The team at the Skokie School has also been prioritizing apps allowing for simultaneous interactions, such as the math app Desmos and Google Jamboard, which both have interactive drawing and digital whiteboard features. These are valuable for visual learners, says Burleson. Nearpod has been helpful for language classes to gauge which videos, polls, or quizzes are working best for students, while also allowing them to set their own pace.

|

Amanda Jones has led virtual “Journeys with Jones,” author chats, and other activities with her students at Live Oaks Middle School in Watson, LA.Images courtesy of Amanda Jones |

Physical to digital

With the library still closed to kids, Burleson has been relying on the online community platform Biblionasium. Like a Goodreads for students, Biblionasium is a virtual book sharing space that Burleson connects to the library’s Destiny ebook collection. As of September, students had added 2,221 books to their virtual shelves, made 931 recommendations, and put 806 books on the wish list. The platform gives Burleson and teachers insight into what students are interested in learning.

“Kids are missing the physical space of the library,” he says. “I think, as much as possible, Biblionasium is trying to fill that need of communication with peers and your teachers and [letting them] talk books in a safe environment.”

Librarians are missing that space for interaction, too. “When I come in in the morning, there’s usually a hundred kids in my library,” says library information specialist Andrea Trudeau. “Now I’m looking at an empty, quiet, still space.”

At the Learning Commons in Alan B. Shepard Middle School in Lake Zurich, IL, Trudeau has also been fostering community-building activities virtually. Ordinarily, every first Friday of the month, she holds an open mic in the café-style space of the Learning Commons. Students show original pieces of art, recite poetry, or play music.

“We’re doing the same thing, except now I’m having the kids record themselves on video, and then they post them onto a Padlet,” an interactive multimedia bulletin board, she says. “We share the Padlet with the community, so it’s a way the kids can still interact with each other and showcase amazing talent.” Students, families, and teachers can interact online and “like” performance videos, providing much-needed social activity and a positive environment.

Trudeau likes to offer a menu of options to increase her reach to students. Recently, she taught the citation management tool NoodleTools to social studies students researching historical events that took place on their birthdays. She ended up conducting eight live presentations on Zoom, creating a video screencast recording with WeVideo, and uploading slide deck screenshots.

“We can’t assume that every kid is going to be there, and we also can’t assume that a kid is going to get it after that first try,” she says. “I’ve learned that you have to offer it in so many different ways. Meet kids where they’re at—some of them aren’t getting it the first time; some of them need one-on-one.”

|

“I’ve really tried to reframe the idea of a challenge as an opportunity this year,” says Andrea Trudeau of the Alan B. Shepard Middle School in Lake Zurich, IL.Photo by Tracy Layne and Linda Vaananen |

Virtual field trips

Inspired by public libraries, Trudeau plans to roll out an adaptation of the Human Library, where students can “check out” a member of the community, hear about their lives and experiences, and have open conversations. In her virtual version, “Kids can hear stories and interact with someone that maybe is different from [them],” she says, envisioning that she may show a recorded presentation by the community member and hold a virtual Q&A. “It’s a way to open their eyes to the world, because we live in a very sheltered community,” she says.

While field trips are on hold, librarian Amanda Jones at Live Oak Middle School in Watson, LA, has been taking students and families around the world—virtually. When the school announced its switch to remote learning last spring, Jones immediately began to develop online activities. Inspired by an article she read about virtual tours, she created her own, called “Journey with Jones.” She taught herself to use Google Slides, Google Earth, and a variety of VR websites. Since March 17, she has hosted more than 20 live virtual tours.

“I didn’t want to just drop the link for the kids” and leave it at that, she says. Like Ms. Frizzle from “The Magic School Bus,” she’ll whisk students to virtual destinations matched with course curriculum. She has explored the Library of Congress, the Smithsonian, Mesopotamia, and ancient Egypt with social studies classes. She partnered with a fellow librarian in Georgia to go on a safari in different ecosystems with science classes. Jones plans to continue hosting the virtual tours and adapt them for in-person instruction in the library. Already, students who have returned to campus under the school’s hybrid reopening plan are stopping Jones in the hallway to suggest places to go next. “They all know who I am now because of this,” she says.

The tours help encourage at-home discussions, too. “Families watch them together,” Jones says. “It’s kind of like an escapism.”

In the first week of school at Jefferson Middle School Academy in Washington, DC, library media specialist K.C. Boyd helped support an icebreaker activity in a social justice class. Participating virtually, the class played GeoGuessr, a geography game where users guess locations based on images and 360-degree-views from around the world. The challenges were conversation starters among kids about different places and social issues, giving them “an understanding of the world they live in, not just in DC, but abroad and how sometimes there are issues that are very, very similar to what we’re experiencing,” Boyd says.

|

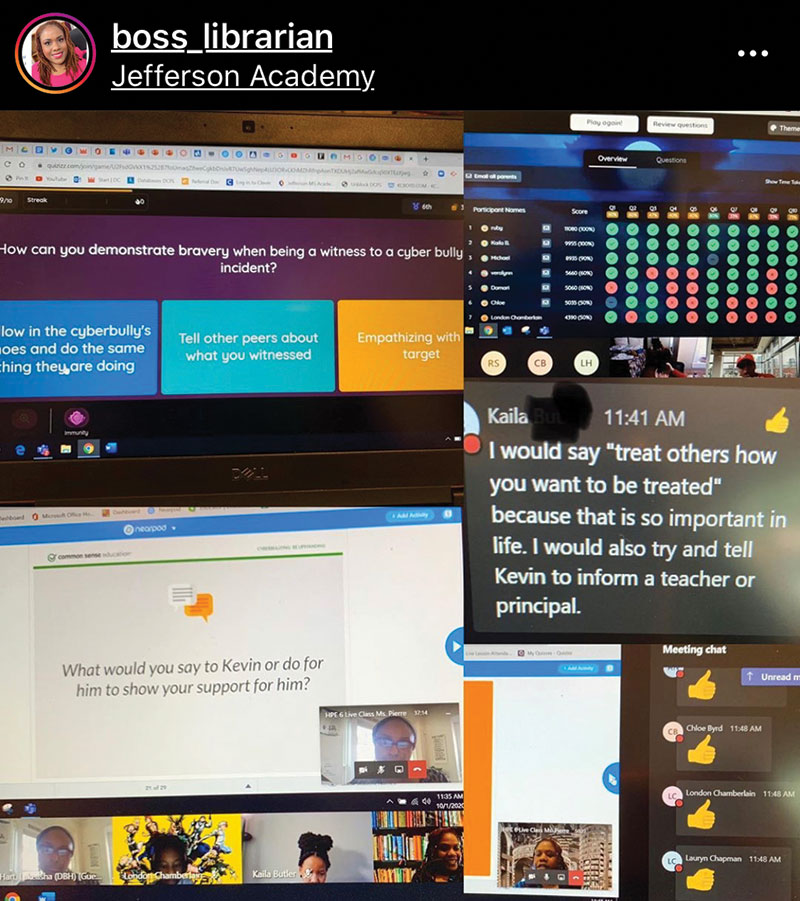

Images from a virtual anti-bullying activity co-led by K.C. Boyd of DC’s Jefferson Middle School Academy.Image courtesy of Torri Pierre, LaKeasha Hart-Tribue, and K.C. Boyd |

Being digitally literate, not just online

Incorporating current events and real-world problems into the learning process is an effective strategy to ensure that lessons resonate with students, Cassinelli says. “That’s what’s going to make it feel more authentic for the kids, especially with remote learning. They can totally tell when an assignment is just busywork to meet some kind of learning target.”

Last year during remote learning, Cassinelli and teachers at Sunset High School participated in a number of activities by the Learning Network from the New York Times. The editors publish contests, forums, writing prompts, crosswords, and other lessons based on stories and news in the paper. “The kids loved it, because they could take what was happening in current events in the world and incorporate it into their writing,” she says.

Cassinelli also discovered the News Literacy Project’s Checkology, a skill-building platform that provides lessons and resources on how to fact-check the media. She had all her freshmen students at Sunset High School sign up to investigate coronavirus information and misinformation in their newsfeeds. They completed the COVID-19 misinformation modules and a reading from NLP’s The Sift newsletter (bit.ly/2GMDBWB). Now that Checkology is free through fall 2020, she’ll expand on her use of the tool.

In October for National Bullying Prevention Month, Boyd partnered with clinical social worker LaKeasha Hart-Tribue and health physical education teacher Torri Pierre on a grant-funded, virtually taught makerspace project for sixth graders on the impacts of violence and bullying.

Combining Common Sense Media, Nearpod, and Microsoft Teams, lessons had students think about cyberbullying, online safety, and the bystander effect. They couched the lessons in current events, for example, discussing youth climate activist Greta Thunberg and the bullying she has experienced on social media.

To unpack and define the concepts, Boyd and the team coupled the word cloud–generating tool worditout.com with a bead-making activity to help them remember antibullying terminology.

“We want them to walk away with these valuable skills that will help them get good grades and be stronger digital citizens,” she says.

In line with this objective, Boyd is teaching an online seventh grade media class where she’s introducing students to various apps and tech platforms. The class will learn how to curate stories and media on Wakelet, navigate Microsoft Teams, design visuals on Canva, and verify information on Checkology.

“A lot of people think that kids are very techie because they’re always online, but that’s just not necessarily so,” Boyd says. “Yeah, they’re reading online, but can they read and comprehend? Can they use digital applications properly, rather than just quickly clicking through? These lessons that we’re creating in a digital world are going to have such an impact on the kids for years to come.”

Remote education has been a learning curve for everyone. Trudeau anticipates more innovation and change when the school transitions into hybrid in-person instruction mid-fall. It’s vital for librarians to [remain] flexible and keep an open mind to stay connected with kids, she says.

“What is going on is so difficult to everybody mentally, emotionally,” she says. “At first, I was focusing on all the things I was losing. But now, I’ve learned to let that go and focus on how I can take what I’m already doing, change it, and see it differently. I’ve really tried to reframe the idea of a challenge as an opportunity this year.”

Lauren J. Young is a science journalist based in New York City.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!