2018 School Spending Survey Report

An Inside Look at Librarians, Schools, and the Political Climate

Librarians around the country share how their workday has changed post-election.

After we asked librarians to describe the political climate in their schools and communities, this much became abundantly clear: They're all trying really hard to be fair and supportive to all, but that isn't so easy in this unprecedented, continually changing landscape. So what are the new rules, if any, for how librarians express their opinions—whether through what they say, wear, or post online—at a time when emotions are running high among colleagues, parents, and students? It’s worth nothing that nearly half the professionals we reached out to did not reply to our invitation to comment, even off the record. Several others would only refer us to district memorandums, which typically offered broad directives, such as “staff should not engage in political discussions during class” or “students should feel safe on campus.” Here’s a snapshot of what librarians around the country were willing to share, describing what the mood is, what they’re doing and saying—and what they’re not.

After we asked librarians to describe the political climate in their schools and communities, this much became abundantly clear: They're all trying really hard to be fair and supportive to all, but that isn't so easy in this unprecedented, continually changing landscape. So what are the new rules, if any, for how librarians express their opinions—whether through what they say, wear, or post online—at a time when emotions are running high among colleagues, parents, and students? It’s worth nothing that nearly half the professionals we reached out to did not reply to our invitation to comment, even off the record. Several others would only refer us to district memorandums, which typically offered broad directives, such as “staff should not engage in political discussions during class” or “students should feel safe on campus.” Here’s a snapshot of what librarians around the country were willing to share, describing what the mood is, what they’re doing and saying—and what they’re not. Montville, NJ

Robert R. Lazar Middle School is in a diverse community, says librarian Suzanne Metz, one comprised of Jews, Christians, Muslims, and Hindus, as well as both Republicans and Democrats. Yet Metz reports that staff hasn’t received any formal rules for political discussion. While students and faculty are, for the most part, discussing politics with discretion, there was one teacher “who freely posted anti-gay and anti-immigrant screeds on social media,” Metz says. “Another teacher complained to our principal. The teacher met with a union rep and the administration; she is no longer employed here.”Austin, TX

At Westlake High School, librarian Carolyn Foote started a lunchtime civil discourse club last fall. In moderating discussions with up to 30 students, Foote worked with a retired teacher of U.S. government to set up lists of questions and expectations for civil discourse. “No name-calling, no ridiculing,” Foote explains. “And try to offer reasons for why you’re saying what you’re saying.” She adds that the group has been especially valuable to students who are Trump supporters in a school where Hillary Clinton won the mock election last November. “I realized that for some students who were adamant Trump supporters, this was an outlet because they weren’t discussing this in class. They didn’t have a format [for these dialogues].” While school policy has prohibited teachers from wearing political paraphernalia long before the 2016 election, administrators did recently remind staff to be "respectful" of colleagues. Foote is careful not to advocate for a particular political stance. “It’s important that students feel you’re trusted to be a moderator,” she explains.St. Louis, IL

East St. Louis Senior High School library media specialist K.C. Boyd says that while she hasn’t received formal guidelines, “Our administration encourages us to have conversations with the students and integrate today's news into our lessons to make them more meaningful.” Of the student body—which is 99 percent African American and one percent Hispanic—Boyd says, “Many echo the feelings of their parents: that some of the changes we have in store may affect their family unit heavily.” So how does she answer those kids’ questions? “Honestly!” says Boyd, pointing fellow librarians to resources. “One source that is helpful is Gale Opposing Viewpoints in Context [a subscription database], which is helpful when students are writing research papers or participating in a class discussion. Another one is Newsela [free], which breaks down today's news so that pre-teens and teens will have a good understanding of headlines.”Leesburg, va

Last November, the Loudon County (VA) Public School District (LCPS), 30 miles outside of Washington DC, issued a reminder that teachers and principals “should not support political candidates or causes during work hours.” However, that does not stop students from asking questions about current events. At one LCPS campus, Tuscarora High School, the student body is about 25 percent Hispanic. “Many of them have expressed fear of being deported,” says librarian Mary Pellicano. “While we are not allowed to ask about a student’s immigration status directly, we do try to offer solace and reassure them of our support.” Tuscarora’s school library collection includes Spanish language books and the bilingual magazine, Motivos. “We were not given explicit instruction about library books, displays, and the like, as our principal is very supportive of the school library and defers to us for best practices and generally trusts our judgment,” says Pellicano.Brooklyn, NY

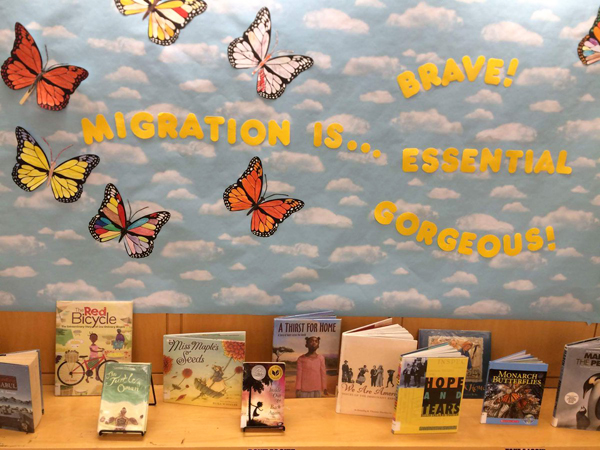

A Brooklyn Public Library display about migration adorned with butterflies and featuring picture books about butterfly or human migration has been shared widely on Twitter. It was created by children’s librarian Katya Shapiro, who works at the Bay Ridge branch, a neighborhood with a large Muslim community, including many Middle Eastern and Arab American families. Shapiro, who describes herself as an “outspoken person,” was inspired by signs at recent marches in reaction to President Trump’s executive orders. She writes messages of welcome and inclusion on a chalkboard, and children have begun spontaneously adding their own messages. “My branch is doubling down on what we believe are basic public library values: welcoming and including all people, providing thoughtful programming, and access to accurate information. I'm very lucky and proud that BPL has been fully supportive at both the local and institutional levels, with communications, programs, and events that promote civil discourse and literacy.”

A Brooklyn Public Library display about migration adorned with butterflies and featuring picture books about butterfly or human migration has been shared widely on Twitter. It was created by children’s librarian Katya Shapiro, who works at the Bay Ridge branch, a neighborhood with a large Muslim community, including many Middle Eastern and Arab American families. Shapiro, who describes herself as an “outspoken person,” was inspired by signs at recent marches in reaction to President Trump’s executive orders. She writes messages of welcome and inclusion on a chalkboard, and children have begun spontaneously adding their own messages. “My branch is doubling down on what we believe are basic public library values: welcoming and including all people, providing thoughtful programming, and access to accurate information. I'm very lucky and proud that BPL has been fully supportive at both the local and institutional levels, with communications, programs, and events that promote civil discourse and literacy.” Lake Villa, IL

While many librarians are creating displays or programming around diversity and tolerance, some are concerned that all political viewpoints are not being discussed fairly. Kellie Piekutowski, information and learning center director at Lakes Community High School, does not have displays or signage around current events. “If I did, I would adhere to ALA's own code of ethics to offer resources on all sides of an argument,” says Piekutowski. “I am seeing posts from my colleagues across the nation in which they are showcasing displays and signage that clearly lean one way on the political spectrum. Even the #librariesresist movement and resource lists are one-sided, providing links to predominately leftist issues, such as Black Lives Matter and the Women's March. Regardless of whether or not I agree on a personal level, my public school library is not the appropriate place to demonstrate. Rather, we need to step away and make room for the students to come to their own conclusions with the help of the fair and balanced resources we offer to them.”Seattle, WA

The week after President Trump signed the executive order banning travel from seven predominantly Muslim countries, Seattle Public Schools issued an email reminding teachers and staff what they can do to help students who are worried or confused by the anti-immigrant, anti-Muslim rhetoric. The advice included check-ins and restorative circles, lessons on separation of power, free speech, and understanding diverse perspectives. However, even in heavily Democratic Seattle, there is a range of political opinions. "I do hear of a variety of voters among our families,” says teacher librarian Craig Seasholes. “So there is a respectful awareness not to scorn other people’s opinions or to overexert one’s political leanings, while encouraging open discussion and tolerance.” Seasholes works at Dearborn Park International Elementary School, which has a large immigrant population and high poverty rate. “As the challenging repercussions of the presidential election reverberates through our community, our school library and information technology program has an ability and responsibility to teach the principles and documents on which our nation is founded,” he says. “As activist-teachers, the need to teach critical, yet respectful, thinking and effective action will serve our better collective selves to ensure all students feel welcome and supported at school.”RELATED

RECOMMENDED

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Deah

My school, located inside the DC Beltway, is an alternative high school designed for students whose educational lives have been disrupted (most often by immigration or parenthood). Two days after the election we held a Town Hall meeting during lunch, where students shared their fears of deportation, of not finishing high school, of not being able to apply for college, of being separated from their American-born children. We did what we could to calm the fears and convince our students of the need to stay in school. Yesterday over half our student body missed the school day due to the "Day With No Immigrants". We try to support our students individually and as a whole with whatever questions or special needs they might have. This past week all staff in our district received a memo from the Superintendent about social media and the appropriate way to label your opinions as your own and not the district's.Posted : Feb 17, 2017 06:04

Susan Paggi

Thank you for articulating in print what I have been trying to sort out in my head and heart.Posted : Feb 17, 2017 05:23