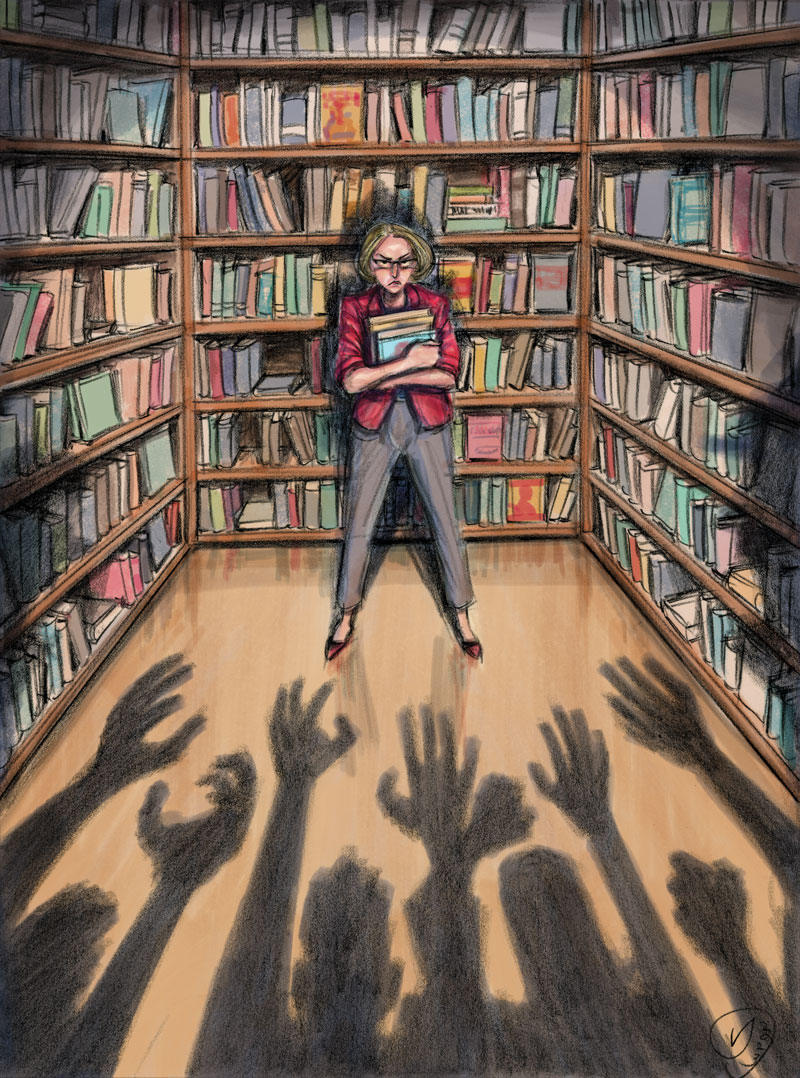

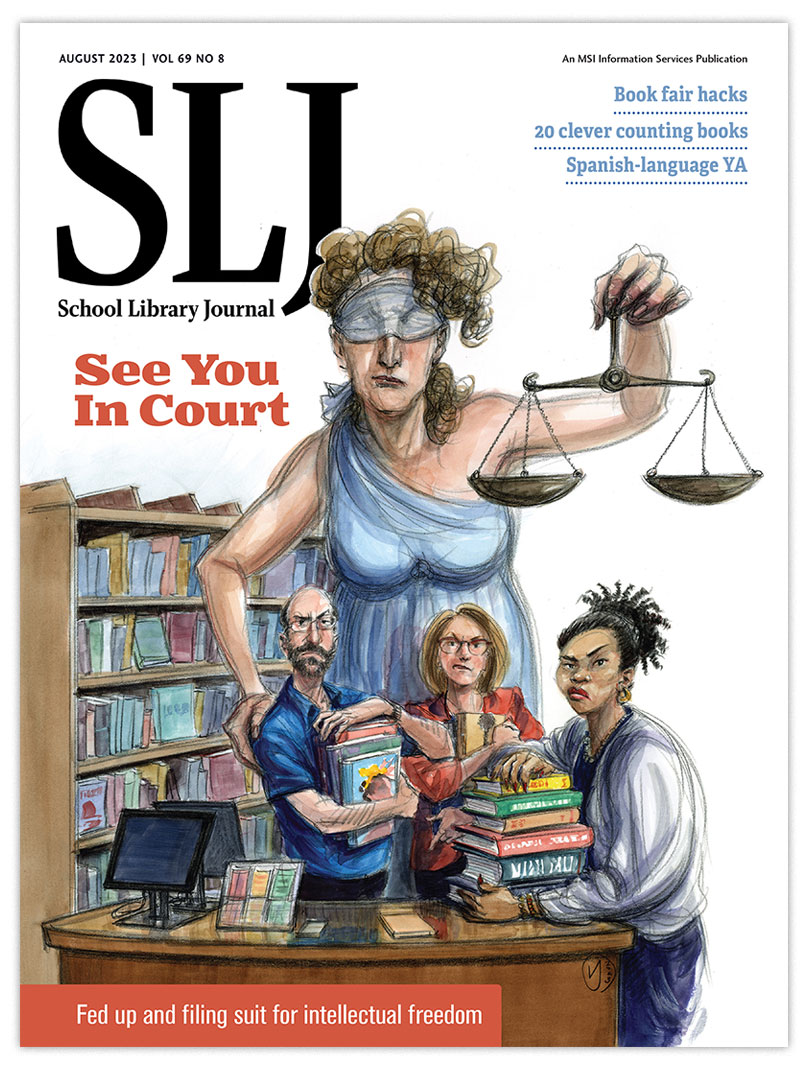

Fed Up and Filing Suit for Intellectual Freedom

Lawsuits are becoming an important tool to fight back against censorship. SLJ spoke with plaintiffs in four cases about what led them here, why they pursued this path, and the goal of the legal action.

|

Illustration and SLJ August cover by Victor Juhasz |

Book bans in the United States are nothing new. From the very first ban in 1637 over a book that critiqued Puritans, to outlawing antislavery books in the 1850s, to blocking books allegedly encouraging Communism or socialism during the McCarthy era, American history is littered with examples of literary censorship.

Current book ban attempts are focused on materials by and about BIPOC and LGBTQIA+ individuals, and those responsible for library collections and classroom curriculum are being personally targeted as well. Civil rights organizations, authors, librarians, parents, and students are increasingly turning to the court to determine whether today’s bans are unconstitutional, as well as to fight back against personal and professional attacks connected to censorship attempts. These cases will not only determine what’s on library shelves, but whether students around the country will have access to a diversity of viewpoints and ideas, and whether librarians and fellow educators will be protected from harassment.

“In the broadest sense, the First Amendment makes clear the U.S. government can’t ban books or censor them based on what they contain,” says Nadine Farid Johnson, counsel and managing director of PEN America Washington and Free Expression Programs. “The books targeted discuss race, racism, and LGBTQ issues, and that’s discrimination by the government and unconstitutional.”

“In the broadest sense, the First Amendment makes clear the U.S. government can’t ban books or censor them based on what they contain,” says Nadine Farid Johnson, counsel and managing director of PEN America Washington and Free Expression Programs. “The books targeted discuss race, racism, and LGBTQ issues, and that’s discrimination by the government and unconstitutional.”

The latest wave of book banning attempts has been marked by vitriolic language and personal attacks. Librarians and authors have been accused of being groomers and pedophiles. Taking legal action is one way to fight back.

Last year, Amanda Jones, 2021 School Librarian of the Year, filed a civil suit against community members who publicly harassed her for speaking up for her local public library. Now, librarian Roxana Caivano is suing residents of her school’s New Jersey town for their attacks on her character and work.

Similar accusations are being flung at children’s book creators.

“You can’t hurt people’s reputations and their livelihoods and arbitrarily decide that what you want your child to read, every other child has to abide by,” says All Boys Aren’t Blue author George M. Johnson, who joined a suit with PEN America, Penguin Random House, and a group of fellow authors. “I think a movement has happened and we’re going to see more and more lawsuits. It will clog up the courts, and eventually someone is going to have to make that ruling that says this violates the Constitution.”

Going to court comes at a cost. SLJ spoke with plaintiffs in four different censorship related lawsuits about what led them here, why they pursued this path, and the goal of the legal action.

|

From the left: George M. Johnson, photo by Vincent Marc; Ashley Hope Pérez, photo courtesy of Ashley Hope Pérez |

PEN AMERICA ET AL v. ESCAMBIA COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD

Plaintiffs: YA authors Ashley Hope Pérez and George M. Johnson

Having a Top 10 book on an end-of-year list is an honor for any author, but when your book is named one of the American Library Association’s Top 13 Most Challenged Books of 2022, there’s far less cause for celebration.

It’s the second year in a row authors Ashley Hope Pérez and George M. Johnson have earned the dubious distinction for having their respective books, Out of Darkness and All Boys Aren’t Blue, banned in at least 29 school districts this year.

In May, Pérez and Johnson and fellow authors Kyle Lukoff, David Leviathan, and Sarah Brannen joined PEN America and Penguin Random House, along with area parents to file a lawsuit against a Florida county they say violated constitutional rights.

“For me, it was an easy choice,” Johnson says. “None of this makes sense, and they’re stepping on First and Fourteenth Amendments. It’s just illegal, and we’re tired of this.”

The suit originally challenged the Escambia County School District and School Board for removing and restricting books from public school libraries “based on an ideologically driven campaign to push certain ideas out of school,” according to the complaint. An amended filing removed the district as a defendant.

The restrictions have largely been driven by a single individual, Vicki Baggett, a language arts teacher in Escambia, who is responsible for challenging more than 100 titles. The suit claims that Baggett admitted she never read the first title she challenged, The Perks of Being a Wallflower by Stephen Chbosky.

“The folks seeking to remove these books are seeking to remove books they won’t even bother to read,” Pérez says. “That they are nonreaders is something that saddens me for them as people, but to let a nonreader decide what other people can and cannot read is quite preposterous.”

The Escambia school board has already voted to remove 10 books, each of which had previously been reviewed and recommended to remain in place by a district-level committee of educators, librarians, and community members. Most of the challenged titles are written by LGBTQIA+ and BIPOC authors and deal with LGBTQIA+ themes and issues of race.

To Pérez, that highlights what’s even more concerning about these challenges, which she says are about more than just banning books—they are also about the “disapproval of certain identities.”

“It has grown into something even scarier, which is restricting literary imagination and the impression that imagining possibilities, imagining different worlds, is dangerous or problematic,” she says.

These suits come at a cost to the districts that may make them think twice.

“If the ruling gets the books back and the school board is paying attorney fees, it sends the message that these actions aren’t cost free,” says Pérez. “Let’s use community resources well, have a process, and find other ways of responding.”

While getting books back on the shelves will be a victory, ensuring that students have access to a wide range of literature that reflects diverse viewpoints and experiences is ultimately what’s at stake in this case.

“Books just deserve to be available for those students who need them,” says Johnson. “That’s what a win looks like.”

|

Nate CoulterPhoto courtesy of Central Arkansas Library System |

FAYETTEVILLE PUBLIC LIBRARY ET AL v. CRAWFORD COUNTY ET AL

Plaintiff: Central Arkansas Library System executive director Nate Coulter

As the largest public library in the state, the Central Arkansas Library System (CALS) serves a population of over 400,000 across three counties, including Little Rock, the state’s capital city. Since taking over as CALS executive director in 2016, Nate Coulter has transformed the system’s 15 branches into spaces offering much more than just books, including free meals for kids and teens, tutoring, and other programs. By any measure, CALS librarians have gone above and beyond to support their community. But a new state law could send them to prison.

Before the judge's temporary block, Act 372 was to go into effect on August 1, 2023. The new law requires that any book considered “harmful” to minors must be shelved in a restricted section. The law also makes it a misdemeanor if a librarian provides a minor access to those materials, a crime punishable by up to a year in prison.

In an opinion piece for The Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, the bill’s sponsor, State Senator Dan Sullivan, compares librarians who provide such materials to pharmacists who illegally sell opioids or doctors who sexually assault patients.

“People who know librarians are outraged at this notion that is so hostile to reality,” Coulter says. “The idea that people in our public library are predators or grooming is obviously very, very hurtful, and insulting, and painful. And if you add to that the threat of going to jail, it’s a horrible scenario.”

The idea that librarians have somehow been exempt from criminal behavior is a myth, he says.

“If librarians were doing things that were harmful to minors, they would be prosecuted,” he says.

Like many librarians around the country, Coulter and his staff have been accused of providing pornography and handing out obscene materials to children.

“Nobody is circulating obscenity in their libraries,” says Coulter. “The bulk of the books targeted have to do with LGBTQ topics or materials, or they are written by LGBTQ authors, and those materials are never going to satisfy the definition of obscenity or pornography.”

Coulter would know. Before he became library director, he spent more than 25 years as a trial lawyer. That experience gave him a head start as soon as Act 372 passed the Arkansas state legislature in February. Coulter knew it wouldn’t take long for it to be signed into law by the governor, and it was clear he needed a judicial strategy.

“We knew there had been parties that were involved in a case 20 years ago that struck down similar language that exposed librarians to jail time,” Coulter says. “We went back to some of those parties and figured out what resources we could harness that would make it affordable for us to take on the state.”

On May 25, the CALS board of directors authorized a federal lawsuit to challenge Act 372. By May 26, they were joined by 17 plaintiffs, including the Association of American Publishers, the American Booksellers Association, the Arkansas Library Association, two area independent bookstores, and a 17-year-old CALS patron.

“It comes down to content they don’t like,” Coulter says. “The idea that libraries are a threat to children is turning reality on its head.”

|

Roxana CaivanoPhoto by Anthony Caivano |

ROXANA M. RUSSO CAIVANO v. THOMAS SERETIS, CHRISTINA SCARBROUGH BALESTRIERE, KRISTIN COBO, and KATRINA ALBO and/or JOHN DOE 1-5, JANE DOE 1-5

Plaintiff: School librarian Roxana Caivano

Roxana Caivano has been the librarian at Roxbury High School for the last 13 years. She came to the profession from the business world, working in consulting and project management, before leaving to raise her kids. While volunteering at their schools, she discovered her love for the library.

Being a school librarian, Caivano says “has been the best job I’ve ever had.” But that feeling has been put to the test this year.

Last August, Caivano received an email from a parent expressing concern over a book in the library’s catalogue, Let’s Talk About It: The Teen’s Guide to Sex, Relationships, and Being a Human.

“I responded that the books are for everyone and where she might not like this particular book, it might be of interest to someone else,” Caivano says. “We went back and forth a few times and she decided to put a challenge in.”

The school formed a committee and determined that the title was appropriate for the collection, but decided to restrict access—moving the book to behind the desk and requiring parental permission for a student to check it out.

That first email was just the beginning. From August 2022 through January 2023, Caivano received more complaints over books in her library, culminating in another formal challenge, this time over Gender Queer by Maia Kobabe.

Once again, a school committee reviewed and approved the book’s return to the shelf, this time without restriction. Unhappy parents turned to the school board. They also turned their ire on Caivano—calling for her to be fired, accusing her of luring children, being a child predator, and putting pornography on the shelves of the Roxbury High library.

Now, Caivano is fighting back through a civil lawsuit against those parents, claiming defamation and libel, according to her husband, Tony Caivano, who is acting as her lawyer. He said these labels are not just smears against her character but accusations amounting to a criminal offense.

“You have to address that in court,” Tony Caivano says. “Part of a librarian’s life is dealing with book challenges. Getting attacked personally, being called these names, that’s not part of the job. That’s the reason why the lawsuit was filed.”

Since March, Roxana Caivano says she has received hate mail and faced personal attacks on social media and continued vitriol during school board meetings. But she’s also received a lot of positive support—a former student emailed to ask if she could help; strangers from around the country have sent cards and letters thanking her for her bravery.

Caivano isn’t backing down. She says if a parent disagrees with a book in her collection, that’s their prerogative, “but there’s no reason another child can’t have it. Plenty of parents are supportive and want these books in the library. I just wish it would come down to that—that parents would parent their own children and not everyone else’s.”

|

From the left: Reba Kruse, photo by Grilliot Photography; Shelia D. Crawford, photo courtesy of Sheila D. Crawford |

PICKENS COUNTY BRANCH of the NAACP ET AL v. SCHOOL DISTRICT OF PICKENS COUNTY

Plaintiffs: Parent Reba Kruse and Pickens County NAACP president Shelia D. Crawford

In September 2022, the Pickens County (SC) School Board held a vote on whether to remove Jason Reynolds and Ibram X. Kendi’s Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You from every classroom, library, and media center in the district.

The book had already been challenged by a parent from D.W. Daniel High School and gone through a formal review process. Both school- and

district-level review committees concluded Stamped was an age-appropriate resource for high school students and aligned with South Carolina Department of Education’s English Language Arts standards.

So it came as a surprise when the seven-member Pickens School Board ignored those findings and voted unanimously to ban Stamped from being accessed by any of the more than 16,000 students throughout the district’s 24 schools.

Now, Reba Kruse, a Pickens County resident and parent, and her partner, along with four other parents whose children attend schools in the district, have joined with the Pickens County Branch of the NAACP to sue the district.

“No legitimate government or pedagogical interest is furthered by removing Stamped, and no such interest was even invoked by the Board,” the suit reads. “Rather, the vote was a calculated decision by seven white Board members to suppress ideas that they personally and politically oppose, in hopes that fewer students would be exposed to them.”

“That’s what’s so egregious in this case, the clear censorship of the ideas in this book,” says Pickens County NAACP President Shelia D. Crawford.

This isn’t the first time the Pickens School Board has acted with such impunity. Last year, the board also ignored school and district committee recommendations and voted to restrict access to Nic Stone’s Dear Martin . Community outrage was so loud the board retreated from an outright ban, but still required parent or guardian approval to check out the book.

“The school board hadn’t been challenged before like that,” Crawford says of the Dear Martin incident. She believes the lawsuit came as an even bigger surprise, one she hopes will be a reminder to the board to “listen more to the whole community instead of just one or two people.”

For Kruse, a military veteran and nurse, joining the suit wasn’t a decision she made lightly.

Having regularly attended school board meetings, she had personally observed “members of our community speak out against this book, and the language and the rhetoric was very violent and threatening,” she says. “I accepted that and made a conscious decision knowing the risk of what I was entering into.”

A white woman who grew up in the deep south, Kruse says she has seen many of the issues wrestled with in Stamped and knows the influence a book can have exposing a young person to other perspectives. As a teen, Kruse says The Autobiography of Malcolm X gave her “ideas and tools about how to fight back” against racism.

“Books and ideas are very powerful, and they can be an amazing tool for positive change,” Kruse says.

Today, she and her fellow plaintiffs want to ensure that teens have the same opportunity to read books that challenge preconceived notions.

“It’s all or nothing,” Crawford says. “We don’t want [Stamped] in one place. We want it replaced in all areas it was removed.”

Andrew Bauld is a freelance writer covering education.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!