Lessons from Building a Brand New School Library

Theresa Bruce created a new school library from scratch—and learned some things along the way that can help any librarian wanting to improve their space, collection, and programming.

|

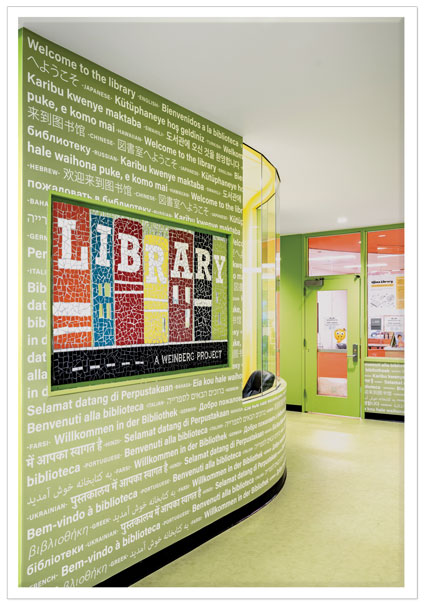

Theresa Bruce’s collection reflects the school community and its interests.Photos by Alan Gilbert |

Imagine having a full year to research, explore, and design a brand-new school library. Theresa Bruce had exactly that, as she was set to become the first library media specialist at KIPP Harmony in the Baltimore City Public Schools district. And she wasn’t just creating one library space—she was going to open two brand new libraries in a building that didn’t have one before.

Starting a school library from scratch is a daunting task, but Bruce took it on with excitement and an open mind as she set to move from the classroom to becoming the librarian of an elementary and middle school library in the preK–8 school.

The former middle school social studies teacher had started a successful independent reading initiative in her eighth grade classroom. When the school sought its first library media specialist, she knew she needed to apply.

“I thought, man, if I could do this with eighth graders—many of them who claim they don’t like reading—why can’t I do it for the whole school?”

The lessons she learned as she built her collection and space en route to opening the libraries last February are valuable to those seeking to improve an existing library and library program as well.

The lessons she learned as she built her collection and space en route to opening the libraries last February are valuable to those seeking to improve an existing library and library program as well.

“If [you] have the time, you have to go out and explore,” says Bruce, who visited public libraries and other schools, checking out programming, makerspaces, collections, classification systems, and physical setups.

“I traveled to different schools—public, private, independent, in state, out of state,” she says. “I interned at different levels of libraries. I went to public library story times. I did all of this research trying to figure out what are the best elements of all these different programs so we could build our program.”

She also sought the knowledge of her peers. If school librarians can get to a conference, go, she says.

“It will change your perspective; it makes all the difference.”

That was the first year. In year two, she put the knowledge into practice.

Bruce created a VIP team of faculty, students, and parents, seeking out faculty members from each grade and reaching out to those she felt would be most passionate about collaborating. She solicited recommendations from staff for students who would be committed to the task, which involved one after-school meeting a month. It was a group that was vital for decision-making about the libraries’ creation, and she still relies on it to help promote the library and engage students and staff.

“The library VIP Team was the best thing that I invested in,” says Bruce. “I call them my brand ambassadors, because all you have got to do is get a few good teachers on your side, and then they start championing the library.”

As part of the VIP team, faculty members commit to collaborating with Bruce. Once other teachers see the results of those efforts, they want to know how they can help, too. She also worked with administrators to get on the schedule to speak during teacher professional development days and makes sure to attend content meetings.

“The social studies team is meeting today, and I know what their curriculum is? Boom. Here I am with a plan,” she says. “‘Let me show you how I can help you and what this will mean.’”

When it comes to the collection, it starts with understanding the needs of your community, she says.

“If you’re revamping your collection, what is it that your kids want? You have to make sure the kids want to read it. Then once that joy spreads, it takes off like wildfire.”

Bruce also created relationships and partnerships outside of the school, collaborating with the public library for things like the Battle of the Books and Library at Lunch, where the public library comes into the school and shares titles from their collection. She also partnered with the Birthday Book Project, so every student gets a free book from the book vending machine on their birthday.

But Bruce’s libraries go beyond books.

With the help of several grants that Bruce received, the library funded a robotics team and hydroponics setup that is currently growing lettuce to share with the school community. Soon the hydroponics program will expand to tabletops in classrooms.

“That’s tying into the science curriculum,” she says. “It also indirectly ties into this idea of food scarcity and insecurity, and how do we help our communities?...

“We want our young people to know that the library is full of knowledge, and that knowledge, while it is in books, is way bigger.”

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!