Adam Gidwitz's Illuminating Medieval Adventure | Under the Covers

Gidwitz, author of the popular "Tale Dark and Grimm" series, discusses his latest work, an ambitious and well-crafted historical adventure set in medieval France.

discover the stories of three children: an oblate on a mission, a Jewish boy fleeing his village, and a young girl who see visions. Add to that a resurrected dog and a farting dragon, and you have a heady mix of history, theology, adventure, and laugh-out-loud humor. Gidwitz was a recent special guest at the Penguin Young Readers fall preview event at their offices in New York City. Before talking to the gathered crowd of eager librarians and educators, Gidwitz sat down with SLJ to discuss this remarkable and charming work. Several weeks later, Gidwitz and his wife Lauren Mancia, a noted medieval scholar and assistant professor of history at Brooklyn College, led a special tour of the Cloisters in upper Manhattan. Mancia described the various artifacts and architectural details of the unique museum while Gidwitz pointed out connections to his Middle Ages–set story. Photos from the event are included below. Why set this new novel in medieval France in 1242? What inspired this setting and what kind of research did you do? My wife is a professor of medieval history. When we met as undergraduates, the first gift I ever gave to her was a surprise trip to York, England. We went to the cathedral in York and to churches to find missing stained glass—it was part of a research project she was doing for her thesis. So, exploring medieval Europe has essentially been my other job for the past decade. We go every summer; I’ve spent about half of my life researching medieval France. I’ve been picking up stories and histories that I think are amazing, settings that blew my mind, and collecting them. About six years ago, I started very seriously organizing them so that they could become a book. On one of these trips, we went to the Jewish History Museum in Paris. We were walking around, looking at the exhibits, and we came to a tiny little plaque—very unassuming, associated with no artifacts. It describes that in 1242 in Paris, King Louis IX—now known as Saint Louis, the most beloved king in the history of France—collected all of the Talmuds of the Jewish people in France and brought them to the center of Paris. And burned them all in front of the Jews. That story shocked me. I couldn’t get it out of my head. Over 20,000 volumes were destroyed. And books back then, before the invention of the printing press, were all handmade. It must have been devastating. That event began catalyzing all of the other stories I had been collecting over the years and it became central to The Inquisitor’s Tale.

discover the stories of three children: an oblate on a mission, a Jewish boy fleeing his village, and a young girl who see visions. Add to that a resurrected dog and a farting dragon, and you have a heady mix of history, theology, adventure, and laugh-out-loud humor. Gidwitz was a recent special guest at the Penguin Young Readers fall preview event at their offices in New York City. Before talking to the gathered crowd of eager librarians and educators, Gidwitz sat down with SLJ to discuss this remarkable and charming work. Several weeks later, Gidwitz and his wife Lauren Mancia, a noted medieval scholar and assistant professor of history at Brooklyn College, led a special tour of the Cloisters in upper Manhattan. Mancia described the various artifacts and architectural details of the unique museum while Gidwitz pointed out connections to his Middle Ages–set story. Photos from the event are included below. Why set this new novel in medieval France in 1242? What inspired this setting and what kind of research did you do? My wife is a professor of medieval history. When we met as undergraduates, the first gift I ever gave to her was a surprise trip to York, England. We went to the cathedral in York and to churches to find missing stained glass—it was part of a research project she was doing for her thesis. So, exploring medieval Europe has essentially been my other job for the past decade. We go every summer; I’ve spent about half of my life researching medieval France. I’ve been picking up stories and histories that I think are amazing, settings that blew my mind, and collecting them. About six years ago, I started very seriously organizing them so that they could become a book. On one of these trips, we went to the Jewish History Museum in Paris. We were walking around, looking at the exhibits, and we came to a tiny little plaque—very unassuming, associated with no artifacts. It describes that in 1242 in Paris, King Louis IX—now known as Saint Louis, the most beloved king in the history of France—collected all of the Talmuds of the Jewish people in France and brought them to the center of Paris. And burned them all in front of the Jews. That story shocked me. I couldn’t get it out of my head. Over 20,000 volumes were destroyed. And books back then, before the invention of the printing press, were all handmade. It must have been devastating. That event began catalyzing all of the other stories I had been collecting over the years and it became central to The Inquisitor’s Tale.

Professor Lauren Mancia (standing) leads the Cloisters tour. This is the Pontaut Chapter House, a room off the main cloister edged with stone benches that served as the inspiration for an early scene in The Inquisitor's Tale.

This work is not just illustrated, but illuminated by artist Hatem Aly. Did you always know that your story would have illuminations? How did the visuals come together? One of the amazing things about the Middle Ages is that readers were much more okay with multiple voices and contradictory voices. You would regularly have a text with illuminations or marginalia or notes that would contradict what the text was saying. One of the most obvious examples of this is the Talmud itself. It has a central block of text and then all these commentators all around it arguing with each other. Rashi, the 11th century Jewish scholar, invented this technique, taking it from a form of Christian exegesis that he learned from an abbot he was working with. So it was very medieval to have these multiple voices interrupting your story. And it was natural for me. In A Tale Dark and Grimm, I’m constantly interrupting the story. We went through a lot of iterations on how we could do that. Early drafts had my own marginalia and notes all around it. But it became impossible to read—there were just too many things going on at once. Then we invited Hatem Aly to illuminate the manuscript. What’s cool is that it’s a different voice, not mine. He’s Egyptian and he lives in Canada, he has a very different perspective on this history than I do. So to get that perspective, to get that voice and diversity of viewpoints on the page, is so exciting. I begged Julie Strauss Grabel, my editor, to let it happen. And she was on-board. What about this book scares you?

An illuminated manuscript from the Cloisters collection. Marginalia can be seen on the lower right side of the text.

To be frank, a lot of things scare me. I am, first and foremost, representing a lot of different people. And a lot of different kinds of people. You have a peasant girl, you have a Jewish boy (I’m Jewish and I was a boy, but I didn’t live in 1242 in France). We have William, a young monk whose mother was of African descent and Muslim, and he is living as a brown-skinned boy in a world where there were no other brown-skinned people that he would have known. So those three in particular, but other characters as well. The multiplicity of perspectives, the diversity of perspectives, is exciting to me but it’s scary. It’s scary to write about because you want to get it right. Now, it’s hard to know what is “right” because these kids lived 800 years ago in France, so, as I say in the afterword, the experience of a brown-skinned person today is very different from back then because they didn’t have our particular and peculiar and awful history. They had a different history. The experience of a Jew then and today would be very different. So I had some freedom, because no one can really call me wrong on these things. Historically, I’m not so worried. Not only is my wife a historian, but she’s part of a wonderful community of professors and scholars, and I sent this book around to many of them and they gave me their notes on their specialty. I feel like I haven’t made glaring errors in history. But really, to represent these diverse characters respectfully and movingly, to give them the voice that they deserve—it’s scary. It’s hard. The main characters in The Inquisitor's Tale are children, but the narration is through adult voices. How did that choice come about? In a very roundabout way. When I was first conceiving the novel, I had this idea—this is a bit of a spoiler— SPOILER ALERT! Yes, this is a spoiler! It was this idea that maybe the kids were being hunted, and the reveal at the end would be that they were being hunted by the narrator. When I had this idea, I was like, “That’s awesome!” But I very quickly abandoned that idea. I thought: I can’t do it. I don’t know how to do it. It’s too hard. I didn’t know how to get into the kids’ heads if I have the person who is chasing them narrate it. He’s too far away—by virtue of chasing them, he can never be with them. And so I abandoned it and wrote the novel in a very “floating close to the shoulder” third person. It was a big novel. Then my editor, Julie, told me the book was not working. It was a hard thing to take. We had some pretty intense conversations. And she said something to me: “You’re running away from storytelling.” I’d had this success with the “Grimm” books, as a storyteller. She said, “Just because you’re a good storyteller doesn’t mean you’re a bad writer.” It kind of shook me. I understood after a while that maybe I wanted to prove that I could write a novel in the third person. So I decided to go back to the storytelling idea and as I was sifting around through my notes I found the idea about the narrator being the bad guy. I wondered: Could I do it? With the intervention of other adult characters who have seen the children along the way—and the one mysterious nun who seems able to peer into their minds—I feel like I was able to pull off the cool reveal and also depict the children wholly. Sounds like you have a really close relationship with your editor. It’s a tough thing to hear that your book isn’t working. We have a very wonderful and contentious relationship. When I get an editorial letter from Julie, the first day is always horrible. She’s just wrong. Then the next day, she’s right. I’m a horrible writer. The third day, I see she’s right but I can’t fix it. By the fourth day, though, I get passed it and get to work. So at least I now understand what my mourning process is like after getting an editorial letter. Though, it wouldn’t hurt her to be a bit nicer. Like the sandwich method? Say something positive, followed by the criticism, ending with something positive again. Yeah, that would be great. She doesn’t do that—it’s just a big piece of meat. In some of your previous novels, you’ve had these iconic figures: Luke Skywalker, Hansel and Gretel. But here you have your own original characters who you’ve built from the ground up. Was that process of creation very different?

A portion of the famous Unicorn Tapestries on display at the Cloisters, here depicting a hound on the hunt. This dog partly inspired Gidwitz's Gwenforte the Greyhound, the holy dog.

It was very different. These characters are original and also much richer characters because of it. There are two kinds of characters in fiction: empty characters and full characters. And I don’t mean that judgmentally. Empty characters are characters that exist for readers to put him or herself inside of. Fairy tales are the classic domain of empty characters. We don’t know anything about Cinderella. We don’t know what food she likes or her opinion on literature. All we know is that she’s a girl and people are mean to her. Therefore, we can pretty much all identify with Cinderella. Luke Skywalker is that way; Hansel and Gretel are that way. To some degree, Harry Potter is that way. A Tale Dark and Grim is, in some ways, about working out our emotions about our parents and our childhoods. It’s a retelling of fairy tales suited to empty characters. A rich historical novel/adventure story is not. It’s suited to full characters. I needed to build these characters in a very different way. What I tried to do is assemble the facts of each child’s life very clearly for myself. Then, I tried to inhabit each child myself. It’s funny that a lot of authors have careers in acting. I’ve spoken to a lot of authors who, in high school or college, were really into acting. I did a lot of acting. Part of the reason is that we enjoy inhabiting characters. When I was writing Jeanne’s scenes, I thought of her situation, what her life was like, and I put myself inside of that and tried to walk around as her. I did the same with William and Jacob. In fact, one of Julie’s criticisms of an earlier draft was that I’d done it too much with Jacob—that he was hard for the reader to see because I was so lost in him. He became me. So I had to pull back and give readers more perspective on Jacob. That reminds me of what Richard Peck said at SLJ’s recent Day of Dialog. He spoke about his journey to becoming a writer. At one point, he spoke about his students and how they, as he put it, “kicked the autobiography out of” him. That’s so right. They demand the stories and you have to just tell them.

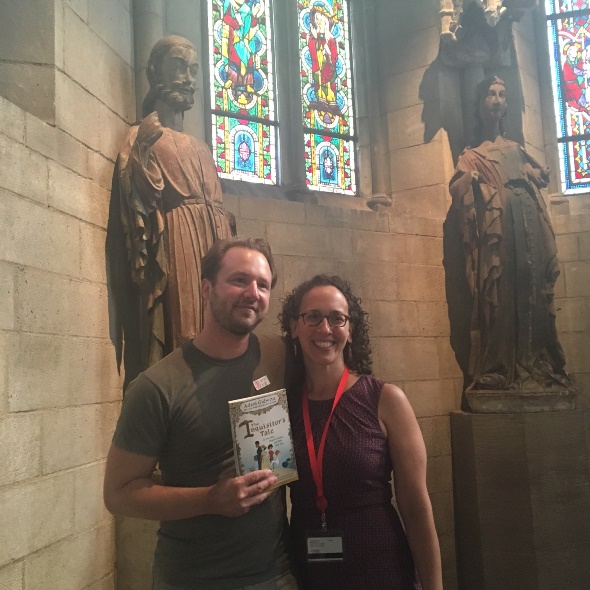

Author Adam Gidwitz and his wife, Professor Lauren Mancia, at the Cloisters.

The settings in this book are so incredibly vivid. You’ve got the castle, the Inn, the village. Do you have a favorite? No competition: it’s Mont Saint-Michel. One of the greatest things my wife and I did on our travels to Europe was a trip to Mont Saint-Michel. It’s a monastery fortress built on a sharp outcropping of rock that comes up from the middle of a bay. Before they built a permanent causeway a few years ago, you could only get there during certain hours of the day. The waters would surround it and it would become an island. Then the waters would recede and the sands would be revealed again. What’s crazy is that because the tides were constantly shifting the sands, a system of quicksand developed around it. There is, literally to this day, shifting beds of quicksand all around Mont Saint-Michel. When we were there, we hired a French guide who lived there his entire life, so he knew exactly where the sands shifted each day. He and his dog took us out into the bay and we walked. He took us to a bed of quicksand and we sank up to our thighs. And he then showed us how to get out of quicksand. The trick is to lie down on your belly and drag yourself out. Well, at least that’s how you do it in the type of quicksand around Mont Saint-Michel. We got out and the sun was setting behind the building. It was among one of the most vivid experiences of my entire life. I got to write about it in the book, which was pretty special. This book works for a variety of readers. There’s tons of action and humor. There’s also a meditation on goodness and the nature of miracles. Your books always hit this sweet spot. No matter how insane or bloody things get, there’s always this exploration of what constitutes a good person. Your books get attention for the blood and the guts, sometimes, but they are extremely valuable in showing kids that questions of morality are universal. Do you intentionally try to strike that balance, or is it a natural outgrowth of your own personality? I really, really love kids a lot. I was a teacher for eight years. Being with them is the most fun thing at any point in my week, in my day. I love to watch kids grow and help them grow. As a teacher, I told my students stories constantly. It was really all they wanted me to do—my lessons were fine, but my stories were good! I never set out to write a story with a lesson. As soon as you try to do that, you’re doomed. But by the end of any story I tell, if there can be an example of children becoming better and stronger and wiser than they were before, then I think that story will be the most powerful, moving, and long-lasting for all the kids I love. Paula Willey is a librarian and blogger at unadulterated.us; Kiera Parrot is the reviews director for SLJ and LJ and the editor of SLJ's Be Tween newsletter.RELATED

RECOMMENDED

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!