Anatomy of a Challenge: A Book Ban in Leander, Texas Presaged a Pattern of Challenges Nationwide

It started with Leander parents who were concerned about curriculum. What happened next epitomizes the wave of other book challenges sweeping the country.

|

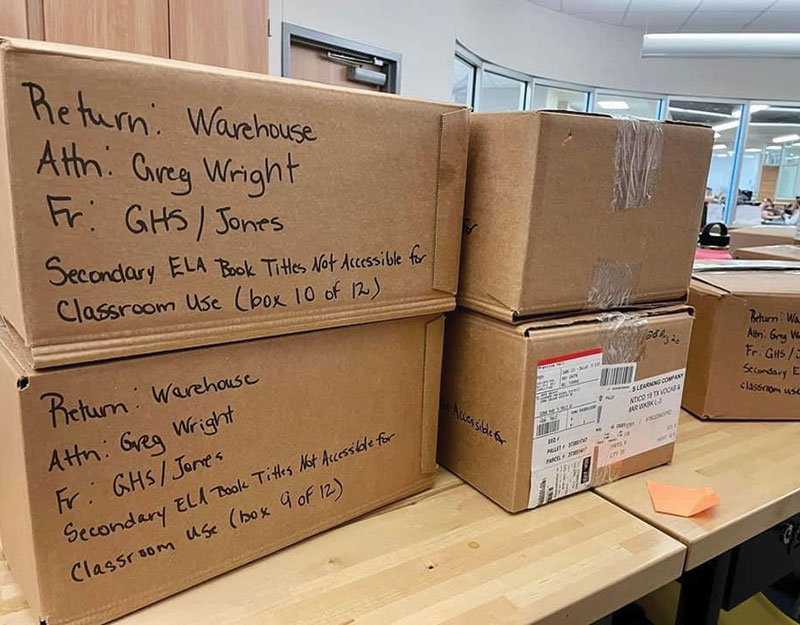

A Leander ISD teacher photographed boxed-up books removed from classrooms.Photo courtesy of Mothers Against Greg Abbott |

In fall 2020, as students began a tentative return to in-person schooling after months of virtual learning and uncertainty, Leander ISD in central Texas sat on the precipice of a new controversy.

To comply with new state standards, the district was rolling out student choice book clubs for high schoolers with a selection of books in English language arts classrooms intended to provide a more diverse range of views and learning experiences. The books were not required reading, but they raised concerns for some parents who thought some titles were inappropriate for their children.

Over the following months, parents began showing up at school board meetings demanding that these books be pulled from classroom shelves and reviewed. But what began as a hyper-local issue in one district soon became national news.

At a school board meeting in February 2021, a parent read a passage from Carmen Maria Machado’s In the Dream House, brandishing a sex toy that was referenced in the book. A video of her speech went viral.

In December, Leander announced its final decision to ban 11 books from classrooms.

While that doesn’t directly impact the school libraries, librarians describe the decision as chilling and unsettling. They say it sheds light on the lack of public awareness of how they do their jobs and why it’s important for libraries to have a wide array of books with different viewpoints.

By the time the decision in Leander was made, book challenges in schools had swept through Texas and other parts of the country. Jonathan Friedman, the director of free expression and education at PEN America, which has been involved in the Leander book challenge battle since early 2021, says what happened there epitomizes book challenges happening across the country.

“You can’t say that it caused everything else, but on some level, a lot of the patterns and trends that we see now spread across Texas and other states did have very strong origins in things that we saw in Leander in the past year,” Friedman says.

Though the issue has now become a political lightning rod, it started with Leander parents who were concerned about curriculum. In a November 2020 school board meeting, about a dozen parents and students spoke to the board about school reading materials as well as a proposed change to the district’s discrimination policy. Many mentioned both issues. Nobody asked for books to be banned, but rather for the curriculum to be reviewed.

“Some of the things that I’ve seen in books that my kids are being exposed to are things that I would think would be rated PG, R—if not X,” one parent said. “As a parent, that’s not what I want for my children.”

Another criticized what he viewed as a Marxist critical framework being taught in his child’s AP English class to the exclusion of other viewpoints. What these parents had in common was summarized in another’s comment: “What gives Leander ISD the impression that they know how to parent our children better than we do? A lot of the topics pushed in the curriculum right now are stuff that I would not allow my children to look at at home.”

Only one parent directly addressed the student choice book club material, and she read a collective statement signed by 15 parents in favor of the books on the list. “These books offer our young readers a wide variety of viewpoints and experiences in life,” she read aloud before the board. “We believe every human experience to be unique and valuable. Through the process of sharing those experiences we all grow. We support the right for students to choose the books they read.”

The final 11

In response to the outcry, the district created a Community Curriculum Advisory Committee, composed of more than 70 parents, teachers, librarians, and other school staff and administrators. The committee reviewed all 140 books on the book club reading lists, asking members to rate them on diversity, student appeal, literary merit, alignment to curricular goals, and age appropriateness and sensitivity. They then voted on whether to keep each book as is, require additional review, or consider removing it from classrooms.

The process for deciding which books to remove, however, was not completely clear. For Red at the Bone by Jacqueline Woodson, for example, 88 percent of committee members voted to keep it, while only four percent voted to consider it for removal due to discussion of sex and graphic descriptions of a few sexual encounters, teen pregnancy, profanity, and drug use. Machado’s In the Dream House was similarly rated, with 80 percent voting to keep the book and 16 percent voting to remove it. Despite the high approval rating, both books were removed, while other books with lower approval ratings were kept on classroom shelves.

The other nine books that were eventually pulled areBrave Face: A Memoir by Shaun David Hutchinson, The Handmaid’s Tale: The Graphic Novel by Margaret Atwood and Renee Nault, None of the Above by I.W. Gregorio, The Nowhere Girls by Amy Lynn Reed, Out of Darkness by Ashley Hope Perez, Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery”: The Authorized Graphic Adaptation by Myles Hyman, Shout by Laurie Halse Anderson,V for Vendetta by Alan Moore, and Y: The Last Man Book One by Brian K. Vaughan. Objections raised about these books range from descriptions of sexual assault and rape to “a negative portrayal of men.”

Friedman was concerned about the criteria the committee used to ultimately decide the fate of the 11 books. “There’s a very particular viewpoint that is being discriminated against in the removal of these books, and that is that the books have a great deal to do with racism, sex, with totalitarianism, with visions of dystopia,” he says.

More organizations across began to speak out. The National Coalition Against Censorship (NCAC) sent a letter to the Leander Board of Trustees in March 2021 offering to help them navigate the book challenges in a way that respects the First Amendment and the freedom to read. The organization also expressed concern that some of the challenged books had LGBTQ themes.

While NCAC doesn’t take a position on individual books, it opposes censorship in all forms. Christine Emeran, NCAC Youth Free Expression Program director, said NCAC advocates for parents’ choice to opt out of certain required reading for their children if they feel it doesn’t align with their values, but the books should still be available for families who want access to them.

“Having more books, more choices, more ideas is always a good idea,” Emeran says. “Whether or not a particular school should teach X book or X author is not our place to say, but they shouldn’t ban it.”

A larger agenda

As school board controversies heated up nationwide ahead of the November elections, some politicians seized on book challenges like the one in Leander to push a bigger agenda. In October, Texas state Rep. Matt Krause (R-Fort Worth) sent a letter to the Texas Education Agency targeting 850 books, asking districts to share whether they have these titles and how much money they have spent on them. North East ISD in the San Antonio area was the first to respond, saying it will review more than 400 books.

In response to Krause’s letter, Leander ISD library coordinator Becky Calzada and three other current and former Texas librarians—Carolyn Foote, Nancy Jo Lambert, and one who wishes to remain anonymous—met to discuss a plan of action. They reached out to their networks and asked people to flood the #txlege hashtag on Twitter with stories about books that had changed their lives for the better. They added another hashtag to their messages, too: #FReadom.

Twitter exploded, and the campaign made national news. Mired in the Leander controversy, Calzada and her librarian colleagues had been inundated with negative messages and accusations. But the Twitter takeover gave them something to unite over.

“Watching it unfold on that day was very powerful, very uplifting, and we noticed how excited it made us feel,” Calzada said. “It didn’t make everything go away, but it gave so many readers hope. It gave librarians hope.”

Since Krause’s letter, school libraries across Texas have faced an increase in book challenges, according to Shirley Robinson, executive director of the Texas Library Association. Librarians are being questioned about their book collection process and the resources they use to make their decisions.

Robinson’s biggest concern is that the people challenging books don’t respect the professionalism of librarians and aren’t aware of the processes in place to deal with book challenges and guide librarians in making informed decisions, including reading professional reviews and making decisions that benefit the entire community and age range of students in the school.

Will the district have my back?

Calzada has been Leander district library coordinator since 2013. Every year, the district has faced a few challenges, but previously parents would raise the issue directly with the librarian and a formal review process would begin if necessary. Now, some parents are bypassing the librarian and the school altogether and bringing their complaints straight to politicians. Gov. Greg Abbott recently called for removing books with “pornography” from school libraries—an accusation that Calzada and other librarians say was never true. “The power of words has a huge impact, and that leaves people feeling afraid for their jobs, wondering, are they going to be supported? Is my district going to have my back? Is my principal going to have my back?” Calzada says.

Local librarians are feeling the pressure. April Stone, a Leander school librarian at Four Points Middle School in Austin, said watching the controversy unfold at the high school level has been unsettling. She hasn’t faced more book challenges than usual—challenges are rare at her school—but she said the situation has created a lot of stress.

Stone continues to use the same process she always has for choosing books: reading professional reviews and selecting appropriate books for middle schoolers—which itself is a challenge, due to the broad 10- to 15-year-old age range. She trusts her experience but wonders more often now if someone will have a problem with one of her book choices.

“I don’t necessarily want to take a risk as much anymore, and I second-guess myself even though I’m a professional who has been in education for 26 years,” Stone says.

Colleen Connolly is a Minneapolis-based freelance journalist who writes about children and education, among other subjects.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!