Getting Schooled: Nonfiction authors tell all about class visits

Nonfiction may not be seen as cool or trendy, but it has traditionally been the meat and potatoes of most library collections. And for many young readers, it’s always in high demand. Recently, with the adoption of Common Core standards, this is even more the case as nonfiction has taken a central role in the Language Arts: reading, literature, writing. Young readers come pre-packaged with questions: what and how, when, where and who, the ever-popular how come, and is it true? That’s a question librarians and teachers get most of all. Hand a third grader a book about space travel: is it true? Give a six-year-old a primer on elephants: is it true? Suggest a biography of a World War II hero to a seventh grader: is this nonfiction? Offer a high school student a book about the Supreme Court: is this real or is it just politics? To help those readers find answers, introduce them to the ways authors of nonfiction seek the truth. Here, three veteran authors describe their experiences visiting with students in classrooms and libraries, where it becomes clear that young people are as interested in the work of writing nonfiction as they are in various fiction genres. Kids genuinely want to understand the world, and that understanding often begins in the histories, biographies, and science books they read. Join Sue Macy, Wendell Minor, and David Adler as they describe their visits and show how exciting it can be for students to peek behind the scenes and learn about the creation of nonfiction books.

Sue Macy

The Magic of “Why?”

Sue Macy

Remember those toddlers who asked “Why?’ hundreds of times a day as soon as they learned to talk? Well, they grew up to be the perfect audience for school visits by nonfiction authors. Writing nonfiction books is all about asking questions and tracking down the answers. Kids who have had the urge to know “Why?” are our kind of people. That said, my most successful visits have been those where the adults were as excited as the students, like Harbor Day School in Corona del Mar, CA, a few years ago.

I knew it was going to be special when the librarian said that because of me, the phys ed teacher was helping a dozen eighth graders learn to ride unicycles. They would perform at the assembly where I spoke about my book, Wheels of

Change (National Geographic, 2011), which looks at how the bicycle changed the lives of women in the 1890s. The librarian also put up an impressive bulletin board with Susan B. Anthony’s famous quote about the bicycle: “Bicycling…has done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world.” Notes went home to parents about my visit, and books were ordered (and arrived!) ahead of time. The agenda was set for three talks about writing nonfiction, the K–8 Wheels of Change assembly, and lunch with social studies faculty. Every detail was planned to perfection and the results were fantastic.

Alas, not every school visit can be perfect. A recent daylong visit found me eating lunch alone, off-campus, and shooting baskets in an empty gym as I awaited several classes that were coming for my afternoon program. It was a day of missed opportunities. The PTA had arranged the visit, but I got the feeling the teachers never bought into the plan and didn’t have the time or motivation to invest in it. I still think my four assemblies were successful. The kids were engaged and asked great questions, and I left teachers with a reproducible summarizing my tips for doing research. But the visit could have had a greater impact if the adults been more involved.

Alas, not every school visit can be perfect. A recent daylong visit found me eating lunch alone, off-campus, and shooting baskets in an empty gym as I awaited several classes that were coming for my afternoon program. It was a day of missed opportunities. The PTA had arranged the visit, but I got the feeling the teachers never bought into the plan and didn’t have the time or motivation to invest in it. I still think my four assemblies were successful. The kids were engaged and asked great questions, and I left teachers with a reproducible summarizing my tips for doing research. But the visit could have had a greater impact if the adults been more involved.

School visits are a great way for kids to meet the people behind the books they read, and for authors to meet their audience.

I love to share my enthusiasm for my subject matter (mostly sports and women’s history) and for writing in general, and I love to answer kids’ questions. And boy, do they ask questions. Some highlights:

Most Frequent Questions: Where do you get your ideas? Did you always like to write? Do you have children? Siblings? Pets? Will you sign my book? loose-leaf paper? dirty napkin from lunch?

Most Surprising Question: (from a third grade girl): Since rifles have a greater range than shotguns, why did Annie Oakley choose to use shotguns in her performances?

Most Memorable Question: Aren’t you too old to like sports? (I was 43 at the time.)

WENDELL MINOR

Picturing Nonfiction As a kid dealing with dyslexia, I was all about pictures: mental snapshots, if you will, of the world around me. To me, reading was about the illustrations that gave me clues to the words that accompanied them. Throughout grade school, reading specialists helped me make that vital connection between the visual and verbal. As my struggles continued, I decided that reading nonfiction was a way of doing double duty: attempting to master reading and satisfy my curiosity about my favorite subjects—nature, science, and history.

As a kid dealing with dyslexia, I was all about pictures: mental snapshots, if you will, of the world around me. To me, reading was about the illustrations that gave me clues to the words that accompanied them. Throughout grade school, reading specialists helped me make that vital connection between the visual and verbal. As my struggles continued, I decided that reading nonfiction was a way of doing double duty: attempting to master reading and satisfy my curiosity about my favorite subjects—nature, science, and history.

It’s no accident that my picture books reflect my passions: Daylight, Starlight, Wildlife (Penguin, 2015) and Galapagos George (HarperCollins, 2014)are perfect examples. Over the past several years, I’ve made it a point to share my struggle with dyslexia and reading comprehension with students. My school visits have been a rewarding experience of also sharing my love of nonfiction subjects. My PowerPoint presentations are specifically geared to each grade level. I bring examples of my sketches, reference photos, original art, and other related material to emphasize the “hidden” work it takes to create a successful nonfiction picture book. I like to say that the book they hold in their hands represents only the top 10 percent of the iceberg, while the research behind it is the essential 90 percent never seen. Children become fascinated by the creative process which starts a dialogue of “how and why.”

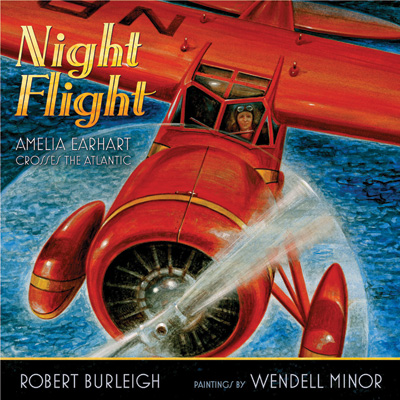

Clockwise from top left: Model shoot in an actual circa 1932 Lockheed Vega (Tom Reid, photographer);

black and white sketch; one of several schematic drawings used for accuracy; A scale

model of Amelia's Vega that she called her "Little Red Bus." Below: The final painting.

To further demonstrate the point, I enhance the connection of the verbal and visual narrative with a read-aloud that brings out the drama of the subject. Robert Burleigh’s Night Flight: Amelia Earhart Crosses the Atlantic (S. & S., 2011) is a good example. Burleigh’s text puts readers in the moment: “She shifts in her seat. She cranes her neck. She squints. She carries on, flying blind. 1:00 a.m. The friendly night becomes a graph of fear: a jagged line between where-I-am and not-quite-sure.” As I read the text and display the images, the “you are there experience” engages children in a great moment in history. Night Flight highlights a historic figure dealing with the advancement of flight science in nature’s harshest elements. I believe that sharing the backstory and reading aloud nonfiction books inspires children to open the door of discovery to that great sense of wonder.

To further demonstrate the point, I enhance the connection of the verbal and visual narrative with a read-aloud that brings out the drama of the subject. Robert Burleigh’s Night Flight: Amelia Earhart Crosses the Atlantic (S. & S., 2011) is a good example. Burleigh’s text puts readers in the moment: “She shifts in her seat. She cranes her neck. She squints. She carries on, flying blind. 1:00 a.m. The friendly night becomes a graph of fear: a jagged line between where-I-am and not-quite-sure.” As I read the text and display the images, the “you are there experience” engages children in a great moment in history. Night Flight highlights a historic figure dealing with the advancement of flight science in nature’s harshest elements. I believe that sharing the backstory and reading aloud nonfiction books inspires children to open the door of discovery to that great sense of wonder.

DAVID ADLER

Investigative Fun

AS A SLAVE FREDERICK DOUGLASS WAS “COMPLETELY WRECKED, CHANGED, AND BEWILDERED.” HE WAS “GOADED ALMOST TO MADNESS.” HOW DO I KNOW? DOUGLASS TOLD ME ALL THAT IN ONE OF HIS AUTOBIOGRAPHIES.

I love to write. I also love talking about the writing process. On school and library visits, as I begin my talk, I look across the audience. One child distracts me. I look at the child a bit too long. At last I start again, and the same child distracts me again. When this happens a third time, all but one child in the audience is laughing. The distracting child is blushing. I ask the child to join me in the front of the room. I point out what caught my attention. It’s always something innocuous.

David Adler in the classroom.

Perhaps the child is wearing pants with a camouflage design or a cardboard birthday crown. The child wearing the camouflage pants would give me the idea to write the story “Invisible in the Third Grade.” The girl wearing the cardboard crown would give me the idea to write “Princess in Kindergarten.” What’s my point? Ideas are everywhere, even for nonfiction. I show them a Sacagawea dollar. Who is this woman on the dollar coin? The coin and my curiosity gave me the idea to write A Picture Book of Sacagawea (Holiday House, 2001).

I tell children about the time I dropped a chocolate chip in a bowl of milk, and it sank. Why did it sink? Then I dropped a chocolate chip cookie in the same bowl and it didn’t sink. That gave me the idea to write Things That Float and Things That Don’t (Holiday House, 2014). Of course, the idea is only the beginning of the writing process. For nonfiction, research is the crucial next step. I tell children that when they research, they need to be resourceful and creative. I’ve written many biographies. As a slave, Frederick Douglass was “completely wrecked, changed, and bewildered.” He was “goaded almost to madness.” How do I know? Douglass told me all that in one of his autobiographies.

Autobiographies are a wonderful source not only of information but also of the subject’s voice. I use lots of quotes in my biographies and I encourage young writers to use them, too. In 1906, Golda Meir and her family moved from Pinsk, Belarus, to Milwaukee, WI. What was Jewish Milwaukee like in 1906? I found out by checking a 1905 Jewish encyclopedia. Tommy Duncan’s mother in Don’t Talk to Me about the War (Puffin, 2009) has multiple sclerosis. How would it be diagnosed and treated in 1940? I found out by consulting a 1940s medical textbook. I used pizza slices to explain fractions in my books Fraction Fun and Working with Fractions (Holiday House, 2007). Researching with pizza was fun. Researching should be fun. Writing should be fun.

Nonfiction ideas begin with questions. Research leads to answers and to more questions. If the subject of a young writer’s nonfiction is something she or he is curious about, both the research and the writing will be fun.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!