2018 School Spending Survey Report

"I'm Nobody! Who Are You?" | Emily Dickinson Plays Sleuth

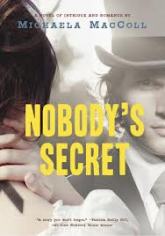

Michaela MacColl is a history scholar drawn to strong female characters, both historical and literary. Her latest novel, Nobody's Secret, features the poet Emily Dickinson, on the trail of a murderer.

In Nobody's Secret (Chronicle, April, 2013), Michaela MacColl imagines the poet Emily Dickinson as a 15-year-old who sets out to discover the identity of a stranger who turns up facedown in her family's pond. MacColl has gravitated toward strong women in her novels: Princess Victoria (Prisoners in the Palace, 2010) and Beryl Markham (Promise the Night 2011, both Chronicle), and she's currently working on a book in which the Brontë Sisters engage in some detective work. "Literary women give writers an opportunity to play with heroines in a way that feels modern but is true to their eras," the author says. MacColl talks about what attracted her to Emily Dickinson, and how the poet became a character in her most recent book. Tell us about your discovery of Emily Dickinson in your girlhood. I remember coming across "Because I could not stop for Death,/He kindly stopped for me;” a poem about being in a carriage with Immortality. What I like about Emily Dickinson is that her work is so accessible. The first four lines of her poems are always visceral, something you see or experience for yourself. To discover that she was writing in the 1850s and 1860s fascinated me. My daughters gravitated to her work, too, without my prodding. When did you begin your quest to learn more about Emily Dickinson? I'd been to Emily's home with my mom. She'd also taken me to see [William Luce’s] The Belle of Amherst, the one-woman show with Ellen Burstyn. In third grade my daughter had to pick someone to put on a Wheaties box, and she chose Emily Dickinson. Since we couldn’t locate a biography of Dickinson that was appropriate for her, I talked to her teacher and asked if I could take her to the poet’s home. So, when I was looking for a new character, Dickinson was in my head. The stories of her, as a recluse, started when she was in her 20s, which is also when she began to write. I was imagining the influences that might cause Dickinson to write later. Do the details drive the story? The person comes first. I was looking for a new project, so I pitched the idea of a series with Dickinson at the center as a detective. Emily's a born observer, and she writes a lot about death. There's a sense of her trying to put things right in the world with her poetry. (It’s not a bad way for a detective to be!) We don't know a lot about Dickinson as a teenager, and that's an opening. Your fictional piece has to be credible. There's an ease with which you include facts about the character of Horace Goodman as a freedman, class distinctions among the residents of Amherst, and Emily’s herbarium. Do those kinds of details find their way in organically? That's the best way. Emily Dickinson's herbarium has been reproduced. With Goodman, I went down a path of freed slaves, and Emily's father represented a family that was trying to repatriate people who had been enslaved. I liked the idea of reminding readers that in the 1840s there were individuals that were not that far from having been owned. "Unsure of the depths of her own faith, she knew she felt it more deeply and with more clarity when she was out of doors." The fact that Dickinson feels God more keenly in nature than in the church is in line with the Transcendentalists, who were writing nearby at the time, isn't it? Dickinson met a number of the Transcendentalists—they'd come to Amherst as guest lecturers. I think they had an impact on her. Her parents had a hard time getting her to go to church. Both were religionists; there must have been so much pressure on her to attend. One of my favorite poems by Dickinson is about worshiping in an orchard ["Some keep the Sabbath going to church—...."] You're a history scholar. What led to your interest in writing historical fiction? When my kids were 4 and 6, we were in Italy, and I was trying to get them interested in what we were seeing. I wanted to create stories where the setting was as important as the characters. I've been writing a story about Michelangelo, up on the hills, looking down at Florence; 600 years later, the center of Florence looks the same. Kensington Palace is a huge part of the novel Prisoners in the Palace; it's its own living, breathing character. For Emily, it's Amherst. I love to write stories about places kids can still go and see.

In Nobody's Secret (Chronicle, April, 2013), Michaela MacColl imagines the poet Emily Dickinson as a 15-year-old who sets out to discover the identity of a stranger who turns up facedown in her family's pond. MacColl has gravitated toward strong women in her novels: Princess Victoria (Prisoners in the Palace, 2010) and Beryl Markham (Promise the Night 2011, both Chronicle), and she's currently working on a book in which the Brontë Sisters engage in some detective work. "Literary women give writers an opportunity to play with heroines in a way that feels modern but is true to their eras," the author says. MacColl talks about what attracted her to Emily Dickinson, and how the poet became a character in her most recent book. Tell us about your discovery of Emily Dickinson in your girlhood. I remember coming across "Because I could not stop for Death,/He kindly stopped for me;” a poem about being in a carriage with Immortality. What I like about Emily Dickinson is that her work is so accessible. The first four lines of her poems are always visceral, something you see or experience for yourself. To discover that she was writing in the 1850s and 1860s fascinated me. My daughters gravitated to her work, too, without my prodding. When did you begin your quest to learn more about Emily Dickinson? I'd been to Emily's home with my mom. She'd also taken me to see [William Luce’s] The Belle of Amherst, the one-woman show with Ellen Burstyn. In third grade my daughter had to pick someone to put on a Wheaties box, and she chose Emily Dickinson. Since we couldn’t locate a biography of Dickinson that was appropriate for her, I talked to her teacher and asked if I could take her to the poet’s home. So, when I was looking for a new character, Dickinson was in my head. The stories of her, as a recluse, started when she was in her 20s, which is also when she began to write. I was imagining the influences that might cause Dickinson to write later. Do the details drive the story? The person comes first. I was looking for a new project, so I pitched the idea of a series with Dickinson at the center as a detective. Emily's a born observer, and she writes a lot about death. There's a sense of her trying to put things right in the world with her poetry. (It’s not a bad way for a detective to be!) We don't know a lot about Dickinson as a teenager, and that's an opening. Your fictional piece has to be credible. There's an ease with which you include facts about the character of Horace Goodman as a freedman, class distinctions among the residents of Amherst, and Emily’s herbarium. Do those kinds of details find their way in organically? That's the best way. Emily Dickinson's herbarium has been reproduced. With Goodman, I went down a path of freed slaves, and Emily's father represented a family that was trying to repatriate people who had been enslaved. I liked the idea of reminding readers that in the 1840s there were individuals that were not that far from having been owned. "Unsure of the depths of her own faith, she knew she felt it more deeply and with more clarity when she was out of doors." The fact that Dickinson feels God more keenly in nature than in the church is in line with the Transcendentalists, who were writing nearby at the time, isn't it? Dickinson met a number of the Transcendentalists—they'd come to Amherst as guest lecturers. I think they had an impact on her. Her parents had a hard time getting her to go to church. Both were religionists; there must have been so much pressure on her to attend. One of my favorite poems by Dickinson is about worshiping in an orchard ["Some keep the Sabbath going to church—...."] You're a history scholar. What led to your interest in writing historical fiction? When my kids were 4 and 6, we were in Italy, and I was trying to get them interested in what we were seeing. I wanted to create stories where the setting was as important as the characters. I've been writing a story about Michelangelo, up on the hills, looking down at Florence; 600 years later, the center of Florence looks the same. Kensington Palace is a huge part of the novel Prisoners in the Palace; it's its own living, breathing character. For Emily, it's Amherst. I love to write stories about places kids can still go and see.  Listen to Michaela MacColl introduce and read from Nobody’s Secret. A discussion guide to Michaela MacColl's Nobody's Secret and suggestions for Common Core aligned activities for grades 7-10 is available from Chronicle Books, along with a trailer.

Listen to Michaela MacColl introduce and read from Nobody’s Secret. A discussion guide to Michaela MacColl's Nobody's Secret and suggestions for Common Core aligned activities for grades 7-10 is available from Chronicle Books, along with a trailer. RELATED

RECOMMENDED

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!