Jacqueline Woodson on weaving memory, crafting poetry, and writing for young adults

Photos by Beowulf Sheehan/Courtesy of National Book Foundation

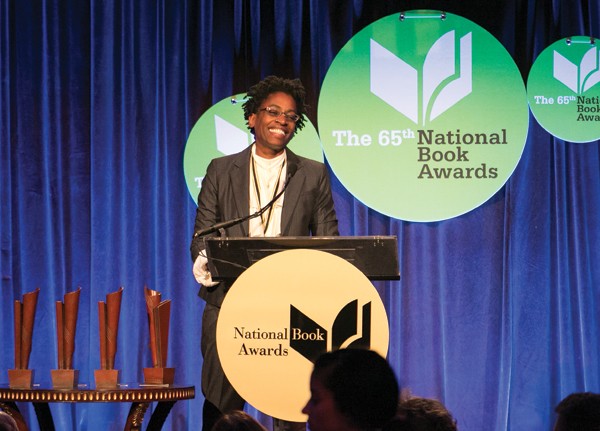

On November 19, in the posh Cipriani Wall Street ballroom in lower Manhattan, writers, publishers, editors, and media gathered to announce and celebrate the winners of the 2014 National Book Awards. Jacqueline Woodson, who’d been an NBA finalist twice before [for Hush (2002) and Locomotion (2003, both Penguin)], rose amid exuberant applause to make her way to the stage, where Sharon Draper handed her the gleaming award. The joy in the room was palpable—even for those watching the livestream online—as Woodson’s megawatt smile beamed over the crowd, eyes shining, hands fiddling with the medal hanging around her neck. She thanked her fellow finalists, the committee, the world of young adult and children’s literature at large, her editor, and her family.

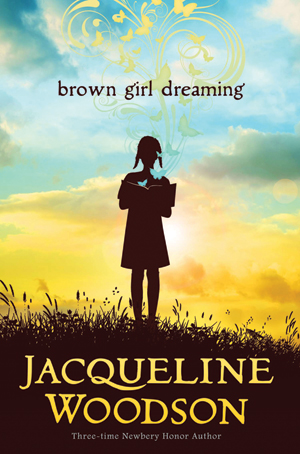

In the moments and then weeks that followed the ceremony, attention would shift away from that buoyant scene to comments made by MC Daniel Handler, including the now-infamous “watermelon joke,” and finally to a broader discussion about respect, understanding, and diversity. Two months later, Brown Girl Dreaming is number four on the New York Times children’s best-sellers list and President Obama was recently spotted purchasing a copy at Washington, DC’s Politics and Prose bookstore.

Heartfelt congratulations on your National Book Award win. You’re no stranger to big-time awards. Was this one different? More exciting or meaningful for you? How did it feel when your name was called?

Heartfelt congratulations on your National Book Award win. You’re no stranger to big-time awards. Was this one different? More exciting or meaningful for you? How did it feel when your name was called? Well, I guess the major difference is the other two times I was a finalist, I didn’t win. This time I did. That doesn’t mean it was more exciting or meaningful—just to be honored feels amazing. I think because I have such a deep respect for the people on the committee, it was deeply felt—to see the love pouring out of the committee and to hear Sharon [Draper] speak about my book, that’s when I teared up. When my name was called, I was a bit stunned and then I thought “I wish my mom could hear this.” It was a mix of emotions. I had so much family in the audience and they were all cheering for me. I exist in a community of amazing people and it was so awesome to have them there being a part of that moment with me.

More than just about any of your other work, this book is extremely personal and revelatory. How long did you work on it? How did you decide that now was the time to write a memoir? Did you worry about the reactions of family members and getting the details just right? Did you always envision it as middle grade?I worked on Brown Girl Dreaming for close to three years I think. I started writing it when my mom died suddenly, but I didn’t know what it was going to be. I just knew that I wanted to deeply understand my past and my mom’s past. And I wanted to understand the world that made me a writer. I started this book as a means of getting answers to questions I had not had a chance to ask my mom and ended it knowing that even though I hadn’t asked those questions, they had always been getting answered. All of my life, my family has been giving me the gifts of books and story and experiences that helped me write not only Brown Girl Dreaming but everything I’ve ever written. So the book feels like an ode to family—to the people who showed me how the ordinary is quite extraordinary and that our history is what buoys us and keeps us moving forward.

The narrative flow is so seamless and organic. Did you write the individual poems in a linear fashion or did you just try to capture various moments and worry about segues and transitions afterward? How did you tap into events and emotions from so long ago and make them so immediate and approachable for today’s readers? How did you decide how much history and backstory to include?There is so much about my childhood I’ve never forgotten. I wrote down these memories and the memories began to weave together the small moments of my childhood. These moments, connected, formed Jacqueline Woodson. Just as I write about discovering how letters make words and words make sentences, the same was true of the book in that each moment became a part of my whole self. To give meaning and immediacy to the text is what I know how to do—hopefully! I mean, I can’t imagine just blowing off my family’s story. They loved me too much for me to do that. Also, in the writing and rewriting of the moments, I was able to spend time with them, go deeper into their journeys.

In your acceptance speech, you spoke about how grateful you were for the deep love of young adult and children’s literature and the fact that the world wouldn’t be complete without all of these many different stories. Given the great momentum of the We Need Diverse Books campaign, do you think that the industry is making strides to put more stories that serve as mirrors and windows into the hands of young readers? Has the face of children’s publishing gotten better since you were a young reader?

In your acceptance speech, you spoke about how grateful you were for the deep love of young adult and children’s literature and the fact that the world wouldn’t be complete without all of these many different stories. Given the great momentum of the We Need Diverse Books campaign, do you think that the industry is making strides to put more stories that serve as mirrors and windows into the hands of young readers? Has the face of children’s publishing gotten better since you were a young reader? I think more than there being more books out there—which there definitely are—there are more people who know about and care about getting these books into readers’ hands. That’s the big change. I believe people are trying. My partner would call that the optimist in me. But there is so much work to do. WNDB has an amazing momentum and is making all kinds of plans and strides so I’m very excited about the future. Last night, Chris Myers was over having dinner with us and we were talking about the situation and he had all of these great ideas. It’s so amazing to be living in this time of great change. It’s hard. It’s complicated. It’s not always pretty—I’m thinking about this week when there are so many protests going on because of Eric Garner and Ferguson and Treyvon Martin—the lists go on—but people are angry and done!—and with anger and done-ness comes change. So it may not always look the way we want it to look or sound the way we want it to sound but it’s change nevertheless. We have to be like water, ready to move with it.

In the wake of Handler’s comments, many bloggers, editors, writers, librarians, and others in the kidlit community responded almost immediately on Twitter and other social media platforms. It seemed that you took a slower, more thoughtful approach to articulate your own reaction. First, in your gracious Guardian response and then more firmly in your New York Times op-ed. I was always taught to “think before you speak.” In the Times piece, you mention that “[Handler’s] historical context, unlike my own, came from a place of ignorance.” It often seems like the burden to educate the ignorant and the uninformed falls upon those who are most victimized by that ignorance. Do you feel a responsibility to help educate your colleagues in the industry? Or do you have more complicated feelings about this? We should first clarify that I wasn’t “victimized” by what Daniel said. You’re giving him an awful lot of power there. I definitely feel a responsibility to share the knowledge I have with whoever wants to hear it. This is what I’ve been taught is the right thing to do. My grandmother would always say, “In all you’re getting, get understanding.” And I believe this. In order to spread respect and understanding, you must first have it. Daniel’s remarks sparked a much-needed conversation. When you received the Margaret Edwards Award in 2006, you told Deborah Taylor in an interview with SLJ that you felt that you were just beginning and that you “still had a lot of work to do and a lot of stories to tell.” Where do you see your work going from here? Do you see yourself writing more YA as your children come of age and become young adults themselves?My work was happening long before my children came along (they’re 12 and 6 now). They definitely showed me the more humorous side of things. I love them like crazy even when they are driving me crazy. I’m not sure what’s next. Brown Girl Dreaming exhausted me—in a good way. I am thinking these days about how important it is to be in the moment and live and love fully—and do what you dream of doing! Even before I had kids, my dream was to spend time with them, love them up, watch them grow, and guide them. Last night my son was at the dinner table telling us about something another classmate said. “I told her that was racist and she didn’t even know what that word meant!” I love listening to their lives. I’ve always believed young people to be a lot deeper than they get credit for being. When my son saw us all leaning in to ask what the girl said, he clammed up. But I know when I’m reading to him tonight, he’ll tell me the whole story. (He doesn’t like an audience!) And I’m glad that this is who I can be and what I can do. I want to do it for my children and for all children—lean in and listen to their Here and Now.

So you’ve written poetry and prose, picture books for the very young, as well as middle grade and young adult novels. When a story comes, whether it’s fictional or a tale from your own family, how/when do you know what form it will take? Which comes first: the story or the form?The character usually comes first, and pretty soon after I start writing. I have a sense of the age of that character. That’s pretty much what determines whether or not it will be for younger or older readers. Then I begin shaping it. My picture books are long poems really—I decide where the lines break and the flow of the story. Sometimes, like with Show Way, there is a lot of internal rhyme. With The Other Side, each line has to lead you to the next with an image. I “see” my picture books in a way I don’t with the older works. With those, I “feel” them more than see them. For example, with If You Come Softly, the light was very much a part of the story and I could feel the effect of the light on different scenes—snow light versus sunlight versus the watery gray light before or right after it rains. There was the light in Jeremiah’s mother’s kitchen that filled him with a sadness and the brightness in Central Park just before… well, you probably know the story.

You knew you wanted to be a writer from a very early age. So, ok, you haven’t won a Pulitzer Prize (yet), but you are at the very top of your game. Have you realized your dream? I’m happy and I feel very, very humbled and grateful for being able to spend my days doing what I’ve always wanted to do. Any advice for young aspiring writers out there? Write. There’s no reason in the world that someone who loves writing shouldn’t be writing.RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!