Leaving China | James McMullan's Peripatetic Childhood

"What the taste of the Madeleine was for Proust the color purple was for me, a dreamlike atmosphere of late afternoon light that encased so many of the scenes that still reverberated in my mind." James McMullan on his art for 'Leaving China.'

On arriving in Cheefoo, China in 1888, James McMullan’s grandparents found a town devastated by floods and a starving population.They founded a nursery for abandoned infants, then a school. Later, family businesses opened, some of which supported a hospital. McMullan was born in 1934 and spent his early childhood in Cheefoo, surrounded by family, and a comfortable expat community supported in part by “the booming economy in that part of China during the prewar years.” In 1937, when the Japanese invaded, it was evident that the life they knew was drawing to an end. Initially the Japanese, allowed “neutral” occupants to remain, but as McMullan notes, “it was clear we were virtual prisoners....” Thus began years of wandering around the globe by McMullan and his mother, followed by the shadow of war, as his father remained behind. In Leaving China, through a series of brilliantly illustrated vignettes, children’s book illustrator McMullan remembers these anxious years and his awakening as an artist. Your life’s work is primarily illustrative–theater posters and children’s book art. Was there an event that inspired you to write this memoir? Finding a box of letters that my mother and father had written to each other during World War ll triggered so many memories of my early life in China, and traveling with my mother to her relatives in Canada and then to India, that I was motivated to write out the story of those years in as coherent way as I could. I realized I had avoided thinking about that period but that I needed, finally, to confront the tensions of my early life. You characterize yourself as a nervous child, but given your childhood in China under Japanese occupation, and the peripatetic years that followed during World War II without your father, nervousness seems such a natural reaction. I suppose nervousness was my natural disposition and that another boy under the same circumstances would have had a “pluckier” reaction to the events. However, the story in the book and the paintings are also a celebration of my endurance and my discovery within myself enough mental strength not to be beaten down by the circumstances of those unstable years and to develop my talent as an artist.

On arriving in Cheefoo, China in 1888, James McMullan’s grandparents found a town devastated by floods and a starving population.They founded a nursery for abandoned infants, then a school. Later, family businesses opened, some of which supported a hospital. McMullan was born in 1934 and spent his early childhood in Cheefoo, surrounded by family, and a comfortable expat community supported in part by “the booming economy in that part of China during the prewar years.” In 1937, when the Japanese invaded, it was evident that the life they knew was drawing to an end. Initially the Japanese, allowed “neutral” occupants to remain, but as McMullan notes, “it was clear we were virtual prisoners....” Thus began years of wandering around the globe by McMullan and his mother, followed by the shadow of war, as his father remained behind. In Leaving China, through a series of brilliantly illustrated vignettes, children’s book illustrator McMullan remembers these anxious years and his awakening as an artist. Your life’s work is primarily illustrative–theater posters and children’s book art. Was there an event that inspired you to write this memoir? Finding a box of letters that my mother and father had written to each other during World War ll triggered so many memories of my early life in China, and traveling with my mother to her relatives in Canada and then to India, that I was motivated to write out the story of those years in as coherent way as I could. I realized I had avoided thinking about that period but that I needed, finally, to confront the tensions of my early life. You characterize yourself as a nervous child, but given your childhood in China under Japanese occupation, and the peripatetic years that followed during World War II without your father, nervousness seems such a natural reaction. I suppose nervousness was my natural disposition and that another boy under the same circumstances would have had a “pluckier” reaction to the events. However, the story in the book and the paintings are also a celebration of my endurance and my discovery within myself enough mental strength not to be beaten down by the circumstances of those unstable years and to develop my talent as an artist.

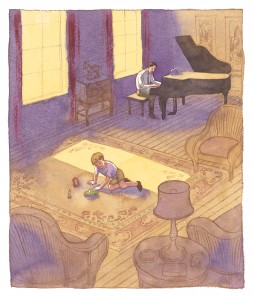

Interior art from 'Leaving China' (Algonquin) McMullan."These memories of late afternoon...as my father sat at the baby grand...happened at that moment when the sun coming through the tall windows would be carved into clear rectangles on the carpet into which I could steer my trucks and cars as they were entering a city of light."

Your childhood sense memories are particularly vivid–the smell of your aunt’s house, the way the light appeared in the room when you were playing, the tone of your mother’s voice during a phone conversation. Did the writing or the painting for the book conjure up the strongest memories? Writing the story and immersing myself in the letters, in the photos from the family album, and letting my mind sink into my own memories of emotional moments, stimulated even more memories of a dog bite, the routine of the house in Cheefoo, my father's singing, the light in the living room. It’s hard to separate what was most powerful in bringing up the past, the writing or painting the illustrations, but since the text preceded the images, I suppose it was the words that first unlocked the memories. But, because using color and physically making the strokes of the painting are, in themselves, such intuitive and emotional actions, the art found other layers of feelings from my childhood that went beyond the simple facts of the incidents in the book. What the taste of the Madeleine was for Proust the color purple was for me, a dreamlike atmosphere of late afternoon light that encased so many of the scenes that still reverberated in my mind. There are many poignant moments in this book, but especially moving was the vignette about boxing coach who took you aside, after your mother enrolled you in his class to toughen you up, who acknowledged that life had something else in store for you aside from sports. His kindness to me was a watershed moment in my life. I think I really became an artist in my own mind because he had released me to say it out loud. My mother had surrounded our life together with the kind of macho men she preferred and many of them, in one way or another, let me know how far I fell short of being the kind of boy they thought I should be. Because Mr. Riley came from the manly world of athletic success his sympathetic understanding of my nature meant all the more to me.

xxx

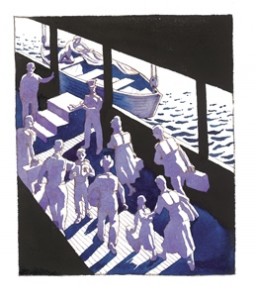

The softness of the art suggests to me that the scenes were painted from memory, rather than photos. Is that so? Because the scenes were so vivid in my mind I was able to draw and paint most of the images from imagination and without reference photos. I say imagination, rather than memory, because my impulse was to summon up the central idea of the memory rather than to re-create it as a journalistic fact. The piano in our living room, for instance, may not have been near the window in exactly the way I portray it, but it was much more important to me to get to the mood of light and time of day than to try to show exactly what the interior of our house looked like. Photographs of our furniture certainly helped me to fill certain images with enough specificity, but I only used that kind of documentation if it served the emotional purpose of the picture. The first picture I completed was the cover image and it established the style of the images in the book. The perspective would be from a high point of view so the figures and elements in the composition would be seen arranged on the plane top to bottom like the subjects in a Chinese scroll. Some of the figures would be painted in a more three dimensional way and some would be described in line drawings. Color, particularly various shades of purple and violet, would be used to establish a dreamlike sense of light and mood. These fundamental choices gave me the freedom in the painting to create esthetically and emotionally and not to have to hew to a stricter kind of realism. Purple and violets infuse the book’s artwork; can you talk about their significance? Some of the color in the book reflects the actual color of Old China, the red tile roofs and the temple columns, but most of my color choices, the purple and sienna, for instance, are based on an intuitive sense of color mood. As the story moves to Canada, the color changes somewhat, including more cool greens, grays, and blues. When I illustrate the story of the bombing scare aboard ship the color becomes almost monochromatic. Have you been back to Cheefoo? I have not. China changed very radically in the years since the war and it seemed that if I went back it would be simply as a tourist and not as somebody able to find the markers of the past. Listen to James McMullan reveal the story behind Leaving China, courtesy of TeachingBooks.net

Listen to James McMullan reveal the story behind Leaving China, courtesy of TeachingBooks.net RELATED

RECOMMENDED

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!