2018 School Spending Survey Report

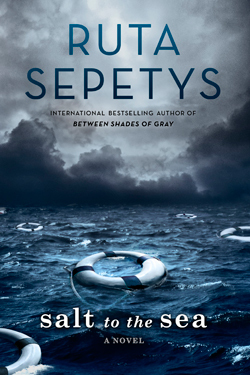

Ruta Sepetys on Unearthing an Untold Story of World War II in "Salt to the Sea"

SLJ caught up with the acclaimed YA author of Between Shades of Gray to discuss her latest historical fiction novel about the world’s worst maritime disaster, Salt to the Sea.

Photo courtesy of Philomel/Penguin.

You mentioned characters, and what I love about this book is that it has four very distinct characters, and some of them are not even that likable. Were you inspired by specific people to write these particular characters? The ship was a German ship, but there were Lithuanians, Latvians, Estonians, and quite a large Croatian crew onboard. There were also some Polish and Czech people. I am very interested in how history is viewed and evaluated when it's viewed through a different historical lens. For example, people from different cultures have experienced the same tragedy, but when I would speak to them, their perceptions, their recollections, were completely different depending on the cultural lens that they were looking through…. Poland and Lithuania [are perspectives] that I'm familiar with—they came very easily. Most difficult probably was the East Prussian narrative…. The people of East Prussian ancestry told me, "Ruta, it's like we didn't even exist. Forty million people prior to the end of World War II, and now, what is East Prussia?" Two of the survivors who I had done a lot of research on were nurses from Lithuania. Their stories were so heroic—how they were separated from their families. They were young and alone. Joanna is the cousin mentioned in Between Shades of Gray. Now, we’re picking up her story in Salt to the Sea, and so that was natural because in Between Shades of Gray, I mentioned that she wanted to be a doctor and pursue medicine. There was a Lithuanian nurse who survived, who very much inspired the story of Joanna. The story of Emilia is more representative of the overall sacrifice of Poland and how Poland is so misunderstood. So many of the Polish people, when I interviewed them, they said, "Ruta, Americans do not understand Poles." They said, "Outside of America, other countries might understand us a little better. They don't understand what we've been through, the sacrifice. They make jokes or Polish joke books about us." And I really wanted to convey that heroic sense through a young girl. Can you tell me a little more about your research process? My first step [was] to find all of the nonfiction and survivor testimonies in print available. And I read those first to really familiarize myself with the geography, with the history, with the facts, and then the next step is to talk to people who either know about this— academics, historians, but, most importantly, survivors. My first stop was in Poland, because the ship sank off the coast of Poland. My Polish publisher found me people [to speak to]. The first was a diver who had been down on the wreck and was so transformed by the experience, because he did not realize that the loss of life had been so large. The Baltic Sea is so clear and so cold, everything was perfectly preserved…. Tragically, I received the same story from several people. They said that when people spoke about the Titanic, “my mom and dad" said, "I was on a ship that sunk." It was so unbelievable, and people doubted them, so they just stopped speaking of it. And then other people told me that their parents didn't talk about it because it was their way of coping…. Food is something that really is a very grounding and defining property of someone's culture. Everything from studying the food and eating the food. I probably don't have to go to those lengths, but for me, it's such a joy…. There's something miraculous that happens when you start to research. I don't know if this happens for all others, but it absolutely happens for me. I go searching for a story in research and the humorous response, and story comes searching for me. One of the most thrilling parts of the research process was, I was maybe even six months into it, and I had been posting some things on Facebook…. I started to receive letters and emails, and some of them had PDF attachments—"Oh, you know, I heard you were writing about this. My mother sailed on the Gustloff before the war just when it was a cruise ship, and here are some photographs." All of these things started coming to me. Then, after I went to Poland, and to England, and to Denmark, and was really doing “boots on the ground” research, I started getting these emails from people saying, "I have an item from the wreck of the Gustloff, and I want you to have it." So I say to the students, “Is this artifact or fiction?” I have items now from refugees themselves, which I cherish…. I have uniforms from crew members from the Gustloff. It's absolutely amazing, I said last night at the USBBY talk that 9,343 people perished when the Gustloff sank. Each one had a story. Imagine if we can honor the victims by learning about their stories, who they were and where they were going and what they were dreaming of and honor their families…. The research leads us to something I hope [is] much bigger—that when struggle is recognized, human dignity can be restored or we can take a step toward restoring human dignity. It's not going to be me who does it, and it's not going to be the book; it will be the conversations that the book inspires, I hope. What was the hardest scene for you to write? There were so many difficult scenes to write, but the hardest scene for me—and again I think this is because I really love this character of Emilia—is when Emilia confesses to Joanna [her secret]. And I don't know; I don't want to give a spoiler to readers, but Emilia's confession to Joanna. Wow, I just—as a writer, like I said, I start with a loose framework and things come together. I try to allow room for an organic process to happen, but inevitably, I become so attached to the characters, and sometimes I feel that the characters are flowing through me. I know this probably sounds ridiculous, but they're flowing through me, and I'm realizing what's happening as I'm writing. I'm writing and I'm writing, and it is happening. With Emilia, as I was writing that part, I was sobbing. I just thought, "Should I do that? That's so awful." And I think other than the fact that your dad and your family are refugees, there was another family connection to this book. Yes. After I wrote Between Shades of Gray, my father's cousins were visiting from Belgium, and they were the ones who told me. They said, "Ruta, there's a secret, a disaster of World War II that no one has written about really in fiction. You've got to cover this." My father fled from Lithuania and made it into refugee camps. My father's cousin, Erica, she also fled from Lithuania but became caught in this area of East Prussia that I focus on the book. And the only way to escape was over water and the family lined up at the port, and Erica was granted passage on the Wilhelm Gustloff…. Erica made me realize that sometimes it's not where you are; it's where you aren't. How many situations have we had where we hear of something that happened and we're like, "Wait. What? I was there five minutes ago," or "I was supposed to be there." But Erica, she did something about it. She begged me to write this book. It also made me realize that even if we weren't part of it, we can still effect change, and we didn't have to be part of it to give voice to it. So speaking of years and years and years, is there anything that you are working on now? I am writing about another underrepresented part of history. In Spain during the Franco regime, over 300,000 of children were stolen from families that did not align with the Fascist regime. And they were given, sold, or bartered to Fascist families, and the world does not know this story…. Last June, I was in Madrid, and I was sitting in a room with 40 people who were stolen babies and now are trying to find their real parents and how terrifying and shocking this whole part of history was. I was there at the meeting when a woman said that her twin brother had been stolen, which was very common among twins. They had told her mother that her brother died. Finally, her mother passed away and her mother had said, "Let it lie. Let it lie," but she decided she was going to exhume that coffin…. In the child's coffin, where her baby brother were supposedly buried—and she never believed the twin brother died—was an adult arm. I'm here in the meeting, and just as an observer. These people are pleading. They're saying, "Look, 300,000 people. This has affected 300,000 people. Argentina has already dealt with their similar situation. Where is Spain? Where is Spain? Where is my brother? This is our national identity. Who are we as people?" That sounds heartbreaking. It is heartbreaking, but there is beauty amid the wreckage. There were people there who also said, "I love my parents. I am terrified. What if I am a stolen baby?" What does it do to a country's identity if there is this option? Maybe you're not who you think you are. So yeah, that's what I'm working on next.

What was the hardest scene for you to write? There were so many difficult scenes to write, but the hardest scene for me—and again I think this is because I really love this character of Emilia—is when Emilia confesses to Joanna [her secret]. And I don't know; I don't want to give a spoiler to readers, but Emilia's confession to Joanna. Wow, I just—as a writer, like I said, I start with a loose framework and things come together. I try to allow room for an organic process to happen, but inevitably, I become so attached to the characters, and sometimes I feel that the characters are flowing through me. I know this probably sounds ridiculous, but they're flowing through me, and I'm realizing what's happening as I'm writing. I'm writing and I'm writing, and it is happening. With Emilia, as I was writing that part, I was sobbing. I just thought, "Should I do that? That's so awful." And I think other than the fact that your dad and your family are refugees, there was another family connection to this book. Yes. After I wrote Between Shades of Gray, my father's cousins were visiting from Belgium, and they were the ones who told me. They said, "Ruta, there's a secret, a disaster of World War II that no one has written about really in fiction. You've got to cover this." My father fled from Lithuania and made it into refugee camps. My father's cousin, Erica, she also fled from Lithuania but became caught in this area of East Prussia that I focus on the book. And the only way to escape was over water and the family lined up at the port, and Erica was granted passage on the Wilhelm Gustloff…. Erica made me realize that sometimes it's not where you are; it's where you aren't. How many situations have we had where we hear of something that happened and we're like, "Wait. What? I was there five minutes ago," or "I was supposed to be there." But Erica, she did something about it. She begged me to write this book. It also made me realize that even if we weren't part of it, we can still effect change, and we didn't have to be part of it to give voice to it. So speaking of years and years and years, is there anything that you are working on now? I am writing about another underrepresented part of history. In Spain during the Franco regime, over 300,000 of children were stolen from families that did not align with the Fascist regime. And they were given, sold, or bartered to Fascist families, and the world does not know this story…. Last June, I was in Madrid, and I was sitting in a room with 40 people who were stolen babies and now are trying to find their real parents and how terrifying and shocking this whole part of history was. I was there at the meeting when a woman said that her twin brother had been stolen, which was very common among twins. They had told her mother that her brother died. Finally, her mother passed away and her mother had said, "Let it lie. Let it lie," but she decided she was going to exhume that coffin…. In the child's coffin, where her baby brother were supposedly buried—and she never believed the twin brother died—was an adult arm. I'm here in the meeting, and just as an observer. These people are pleading. They're saying, "Look, 300,000 people. This has affected 300,000 people. Argentina has already dealt with their similar situation. Where is Spain? Where is Spain? Where is my brother? This is our national identity. Who are we as people?" That sounds heartbreaking. It is heartbreaking, but there is beauty amid the wreckage. There were people there who also said, "I love my parents. I am terrified. What if I am a stolen baby?" What does it do to a country's identity if there is this option? Maybe you're not who you think you are. So yeah, that's what I'm working on next. RELATED

RECOMMENDED

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!