2018 School Spending Survey Report

One Story That Should Change How We Teach History | Consider the Source

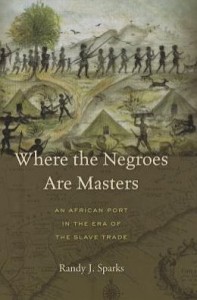

A lively conversation with a "sparkling" group of seventh grade students and their teachers, and Randy J. Sparks's latest book has led the author to a radical conclusion.

Last week I had the chance to visit the beautiful Burgundy Farm Country Day School in Alexandria, Virginia–a school founded in 1946 to create a diverse and interracial environment as an alternative to the entirely segregated public and private schools in the area. I spoke with the 7th graders about race, slavery, and history, and several teachers and administrators came to listen and join in on the conversation. We had a lively discussion and that sparkling class, along with several discussions I had after it, and Randy J. Sparks’s Where the Negroes Are Masters (Harvard University Press, 2013), led me to this conclusion: we need to entirely rethink and reconfigure how we teach race, slavery, the American Revolution, and indeed, U.S. and World History from the 18th century through the 20th century. One teacher at the school recounted to me that as one of a group of undergraduates who studied in Ghana, she and the other African American students were taken aback when they were constantly referred to as “white.” Moreover, many in Ghana viewed those who had made the Middle Passage as weak–as a conquered people. When I told this story to a neighbor who is of Nigerian and European heritage, he described a similar experience-of being referred to as white when he and his Nigerian mother spent time in her homeland. White was not a matter or color–it was related to being foreign, different, shaped (or tainted) by other peoples. We so often recount the pageant of people who came to our shores (voluntarily or involuntarily) as a saga of those who made the most of new conditions, succeeding even in great adversity, that we rarely look at how that story is told by those who remained in their homelands. Once we tell that story–as it actually took place with an eye on both those who left (or were enslaved) and those who stayed (or enslaved)–we have the beginning of a new world history. I found an excellent entry into that history in Sparks’s carefully researched, completely engaging academic book. Sparks recounts a story that is so telling, and so profound in its implications, that it should be explored in every school in the land–and used as a touchstone for a new way of describing the birth of America. Sparks focuses on the West African city of Annamboe (now in Ghana), a crucial port in the Atlantic slave trade. In the mid-1700s the key man in Annamboe was an African named John Corrantee. Corrrantee controlled the slave trade–bringing enslaved Africans to be sold to Europeans–and, in turn, the trade of European goods into the African interior. The French and the English recognized his importance and vied for his favor–while he played them against one another. In the early 1740s, eager to undermine the more dominant English, the French offered to take one of Corrantee’s sons to France. His son Bassi did indeed arrive in Paris where he learned French and King Louis XV acted as his godfather. Not to be outdone, the British offered to host another son–this one considered of higher status. Bassi’s mother was a woman enslaved to Corrantee; William, who sailed off toward England in 1747, was the son of a free woman. This is where the story twists. The captain of the ship died, and when it reached Barbados, William’s status changed. He was no longer the son of a key ally and trading partner of the British, he was potential property. William was kidnapped and enslaved. On learning of William's fate, the elder Corrantee used all of his power to free his son. Once free, William sailed to England where he was the toast of London. Indeed, in 1749 he attended a popular play of the time, Oroonoko, which was a fictional tale of “an African slave-trading prince who was captured and sold into slavery.” William left the theater in tears–and all London retold the story. Indeed the anguish of this African prince helped establish the image of noble Africans and fed a strand of (sometimes patronizing) abolitionism in England. What this story shows: 1) Africans were deeply involved in the African slave trade–leaving the heritage that returning African Americans experience to this day. Indeed Sparks explores in some detail the “country marriages” between Europeans and Africans that resemble, in ways, the tangled family/power/emotional connections that Annette Gordon-Reed explored in The Hemingses of Monticello (Norton, 2009). 2) The idea of slavery as linked to race was both beginning to take hold—William’s kidnapping— and was also capable of being trumped by other narratives—as when William's nobility and royalty mattered most in London. 3) The power of the ideas of hierarchy and nobility in England, as well as the appeal of an image of foreign peoples as subservient and humble. 4) Linking all of these relationships was a world economy in which individual Africans, Europeans, and North and South Americans were traveling far and wide seeking their own individual advantages. Think of how differently we usually tell the next beat in U.S. history: as a two-sided conflict between freedom-loving Americans and rigid British, or as a conflict solely within America between ideas of liberty that favored property owners and views that favored all human beings. The episode recounted by Professor Sparks shows all of these ideas in motion and shape-shifting in different locations–as they would continue to be for the next 200 years. William’s story is a window into a period of great tectonic clashes and shifts in ideas throughout the planet. At the price of millions of lives, people began to recognize a new truth, one whose implications we still debate to this day: no matter how different someone may be from us–in origin, appearance, faith, gender, sexuality, behavior–we never have the right to own, to master, that person. That sterling view, that diamond of human development, was not solely created by John Corrantee’s tactical skill, nor the greed of the Bajan slavers, nor the sentiments of the English, nor the restive North Americans resistant to English dominance. Rather it was forged as the intense ideas, economic aims, and political goals in all of these locations crashed together in enslavement, revolution, capitalism, emancipation, and ever-expanding ideas of human freedom. What a crucial epic for all students to explore.* I suggest that every teacher who covers American history from middle grade up read Sparks’s book and think about how to weave his scholarship, and the story of John Corrantee and his sons, into our national story. Perhaps the good folks at Burgundy Farms can take the lead. * Dr. Thomas Bender, who has been a leader in developing a view of U.S. history as World history, suggested that teachers and librarians interested in this global view should also read Dr. Ira Berlin’s "From Creole to African: Atlantic Creoles and the Origins of African American Society in Mainland North America," William and Mary Quarterly, 53 (1996), 251-88.

Last week I had the chance to visit the beautiful Burgundy Farm Country Day School in Alexandria, Virginia–a school founded in 1946 to create a diverse and interracial environment as an alternative to the entirely segregated public and private schools in the area. I spoke with the 7th graders about race, slavery, and history, and several teachers and administrators came to listen and join in on the conversation. We had a lively discussion and that sparkling class, along with several discussions I had after it, and Randy J. Sparks’s Where the Negroes Are Masters (Harvard University Press, 2013), led me to this conclusion: we need to entirely rethink and reconfigure how we teach race, slavery, the American Revolution, and indeed, U.S. and World History from the 18th century through the 20th century. One teacher at the school recounted to me that as one of a group of undergraduates who studied in Ghana, she and the other African American students were taken aback when they were constantly referred to as “white.” Moreover, many in Ghana viewed those who had made the Middle Passage as weak–as a conquered people. When I told this story to a neighbor who is of Nigerian and European heritage, he described a similar experience-of being referred to as white when he and his Nigerian mother spent time in her homeland. White was not a matter or color–it was related to being foreign, different, shaped (or tainted) by other peoples. We so often recount the pageant of people who came to our shores (voluntarily or involuntarily) as a saga of those who made the most of new conditions, succeeding even in great adversity, that we rarely look at how that story is told by those who remained in their homelands. Once we tell that story–as it actually took place with an eye on both those who left (or were enslaved) and those who stayed (or enslaved)–we have the beginning of a new world history. I found an excellent entry into that history in Sparks’s carefully researched, completely engaging academic book. Sparks recounts a story that is so telling, and so profound in its implications, that it should be explored in every school in the land–and used as a touchstone for a new way of describing the birth of America. Sparks focuses on the West African city of Annamboe (now in Ghana), a crucial port in the Atlantic slave trade. In the mid-1700s the key man in Annamboe was an African named John Corrantee. Corrrantee controlled the slave trade–bringing enslaved Africans to be sold to Europeans–and, in turn, the trade of European goods into the African interior. The French and the English recognized his importance and vied for his favor–while he played them against one another. In the early 1740s, eager to undermine the more dominant English, the French offered to take one of Corrantee’s sons to France. His son Bassi did indeed arrive in Paris where he learned French and King Louis XV acted as his godfather. Not to be outdone, the British offered to host another son–this one considered of higher status. Bassi’s mother was a woman enslaved to Corrantee; William, who sailed off toward England in 1747, was the son of a free woman. This is where the story twists. The captain of the ship died, and when it reached Barbados, William’s status changed. He was no longer the son of a key ally and trading partner of the British, he was potential property. William was kidnapped and enslaved. On learning of William's fate, the elder Corrantee used all of his power to free his son. Once free, William sailed to England where he was the toast of London. Indeed, in 1749 he attended a popular play of the time, Oroonoko, which was a fictional tale of “an African slave-trading prince who was captured and sold into slavery.” William left the theater in tears–and all London retold the story. Indeed the anguish of this African prince helped establish the image of noble Africans and fed a strand of (sometimes patronizing) abolitionism in England. What this story shows: 1) Africans were deeply involved in the African slave trade–leaving the heritage that returning African Americans experience to this day. Indeed Sparks explores in some detail the “country marriages” between Europeans and Africans that resemble, in ways, the tangled family/power/emotional connections that Annette Gordon-Reed explored in The Hemingses of Monticello (Norton, 2009). 2) The idea of slavery as linked to race was both beginning to take hold—William’s kidnapping— and was also capable of being trumped by other narratives—as when William's nobility and royalty mattered most in London. 3) The power of the ideas of hierarchy and nobility in England, as well as the appeal of an image of foreign peoples as subservient and humble. 4) Linking all of these relationships was a world economy in which individual Africans, Europeans, and North and South Americans were traveling far and wide seeking their own individual advantages. Think of how differently we usually tell the next beat in U.S. history: as a two-sided conflict between freedom-loving Americans and rigid British, or as a conflict solely within America between ideas of liberty that favored property owners and views that favored all human beings. The episode recounted by Professor Sparks shows all of these ideas in motion and shape-shifting in different locations–as they would continue to be for the next 200 years. William’s story is a window into a period of great tectonic clashes and shifts in ideas throughout the planet. At the price of millions of lives, people began to recognize a new truth, one whose implications we still debate to this day: no matter how different someone may be from us–in origin, appearance, faith, gender, sexuality, behavior–we never have the right to own, to master, that person. That sterling view, that diamond of human development, was not solely created by John Corrantee’s tactical skill, nor the greed of the Bajan slavers, nor the sentiments of the English, nor the restive North Americans resistant to English dominance. Rather it was forged as the intense ideas, economic aims, and political goals in all of these locations crashed together in enslavement, revolution, capitalism, emancipation, and ever-expanding ideas of human freedom. What a crucial epic for all students to explore.* I suggest that every teacher who covers American history from middle grade up read Sparks’s book and think about how to weave his scholarship, and the story of John Corrantee and his sons, into our national story. Perhaps the good folks at Burgundy Farms can take the lead. * Dr. Thomas Bender, who has been a leader in developing a view of U.S. history as World history, suggested that teachers and librarians interested in this global view should also read Dr. Ira Berlin’s "From Creole to African: Atlantic Creoles and the Origins of African American Society in Mainland North America," William and Mary Quarterly, 53 (1996), 251-88. RELATED

RECOMMENDED

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Monica Edinger

Thanks for this book recommendation. I too would like to us in the US to provide students with a more nuanced look at what was happening in Africa at the time of the Transatlantic Slave Trade. I've got on the back burner a book on Bunce Island, a slave fort in Sierra Leone, most of it focused on what was happening there rather than in the US. What has struck me in working on it is how to both acknowledge the absolute horror of chattel slavery and Europe's complicity while also recognizing that Africans were not just simple folk ripe for manipulation, but strong and political players too. While mostly on things that happened in this country, I appreciate Albert Marrin's presentation of this in his new book on John Brown, A Volcano Beneath the Snow.Posted : May 18, 2014 04:26

Tina Sanders

I remember as a student in Texas being told that in Mexico, the fall of the Alamo was not told as a heroic tale where many Mexican soldiers died by the hands of a few brave whites who fought to the death, but where only a few Mexican soldiers were killed in the taking of the Alamo. Then in church, I was told that in Egyptian history of the pharaohs, there probably isn't much mention of Moses because they only reported successful events in their histories. My eyes were TRULY open to the differing views of historical events when I traveled to Israel in 2001. When visiting the Holocaust museum, there is very little mention of American contribution to the war. As you walk in to the entry gardens, there is a huge monolith in memory of the people who died in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. When talking to our pastor, she said that the older people of Israel blame the Americans for the many deaths during the Holocaust because the U.S. didn't join the war effort soon enough. It definitely makes a person learn that there is two sides to every historical story.Posted : May 09, 2014 07:05