Authors Tackle Complex Topics in Children’s Nonfiction

Betsy Bird looks at the state of children's nonfiction. In many ways, with nuanced and interesting topics, it is the "golden age of informational books for kids," she says. But it's also a time of unprecedented book banning—and that includes many nonfiction titles.

Is nonfiction for children better now than ever? That’s a difficult question to answer. The genre has existed for years, but often occupying that gray area where fictional elements meld seamlessly with informational texts. The first Newbery and Caldecott winners (The Story of Mankind in 1922, by Hendrik Willem van Loon, and Animals of the Bible, in 1938, text by Helen Dean Fish, illustrated by Dorothy P. Lathrop) are classified as nonfiction titles. As such, nonfiction has been deeply rooted in American children’s books from the very start.

In the last 25 years, even more emphasis has been placed on what constitutes great nonfiction for young readers. In 2001 the ALA established the Robert F. Sibert Informational Book Medal for the year’s “most distinguished informational book,” and ever since, the number of nonfiction books has grown, their subject matter increasingly addressing topics once thought too difficult for children.

Biographies now tackle the lives of people who weren’t always laudatory, or who led complicated, even problematic, lives. And sophisticated topics like sex, death, environmental anxiety, or the history of race relations and bias are now addressed, though handled with care. Books for kids also often attempt to show two sides to a subject in an informed, balanced way. With more nuanced and interesting topics available to young readers, in many ways we are living in a golden age of informational books for kids.

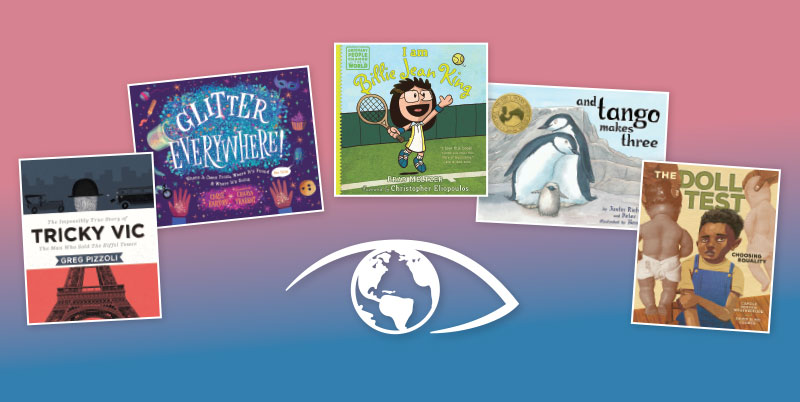

We are also living in a time when books, including nonfiction, are being banned in unprecedented numbers. PEN America’s “23 Most Banned Picture Books of the 2023–2024 School Year” included And Tango Makes Three by Peter Parnell and Justin Richardson and illustrated by Henry Cole, a picture book based on a true story about two male zoo penguins who raise a penguin chick together, and the biography I Am Billie Jean King by Brad Meltzer, illustrated by Christopher Eliopoulos, about the tennis legend who is married to a woman. Book banners may seek to limit children’s books based their definition of what is “good” or “bad” for children. But with subject matter tackled in a developmentally appropriate way, many topics that parents and teachers have historically struggled to explain to children are now being addressed deftly by some of the best storytellers in the field.

Remarkable, fallible people

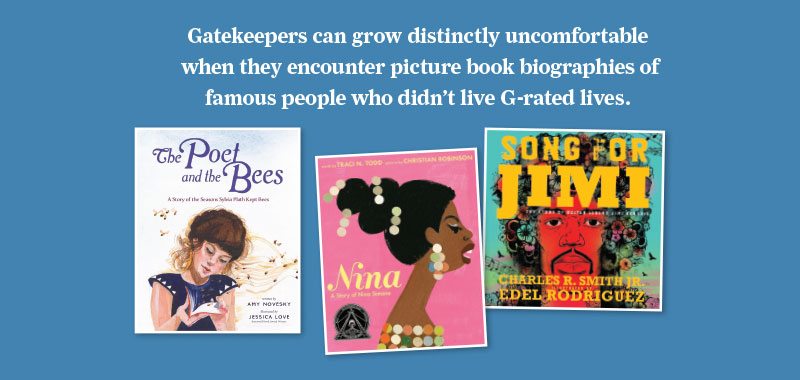

Gatekeepers can grow distinctly uncomfortable when they encounter picture book biographies of famous people who didn’t live G-rated lives, like Traci N. Todd’s Nina: A Story of Nina Simone or Amy Novesky’s The Poet and the Bees: A Story of the Seasons Sylvia Plath Kept Bees. Iconic figures are so much more than their addiction, their mental illness, or their tragic deaths. Children’s book creators are now exploring the multifaceted nature of talented, complicated people, rather than a singular censored story that was the norm and most have come to expect.

In describing his book on Jimi Hendrix (Song for Jimi), Charles R. Smith Jr. says, “People would mostly talk about how he died, so I wanted to show his life from [the time he was] a young boy and how he became such a force in music. I didn’t end with his death because I wanted it to end when he became a star, when he was ‘born.’ So even though each book is different, it’s true to the subject matter.”

Greg Pizzoli’s aim as a children’s book author is simple: “There’s that theory that children’s books must be educational or instructional, and must teach children all the many ways that virtuous children must behave, in way that makes them easier to control by adults. As a creator, that is not my goal. My goal is to make books that kids will love to read.” But when Pizzoli wrote the biographical picture book Tricky Vic—about Victor Lustig, the con man who “sold” the Eiffel Tower (twice!)—one vice principal accused him of encouraging children to become con artists.

The idea of writing a book about a person who was less than virtuous is anathema to adults who may have grown up reading laudatory bios like the “Childhood of Famous Americans” series. But as Candace Fleming (author of books on sometimes unscrupulous men like The Great and Only Barnum and Presenting Buffalo Bill) is quick to point out, “History isn’t written simply to elevate the lives of those we admire. It’s also written to tell us what happened—honestly and fully—and how people from the past fit into our times. By choosing not to write—or read—about the unconscionable and unjustifiable, we are forever bound to the mistakes and misfortunes of previous generations.”

The idea of writing a book about a person who was less than virtuous is anathema to adults who may have grown up reading laudatory bios like the “Childhood of Famous Americans” series. But as Candace Fleming (author of books on sometimes unscrupulous men like The Great and Only Barnum and Presenting Buffalo Bill) is quick to point out, “History isn’t written simply to elevate the lives of those we admire. It’s also written to tell us what happened—honestly and fully—and how people from the past fit into our times. By choosing not to write—or read—about the unconscionable and unjustifiable, we are forever bound to the mistakes and misfortunes of previous generations.”

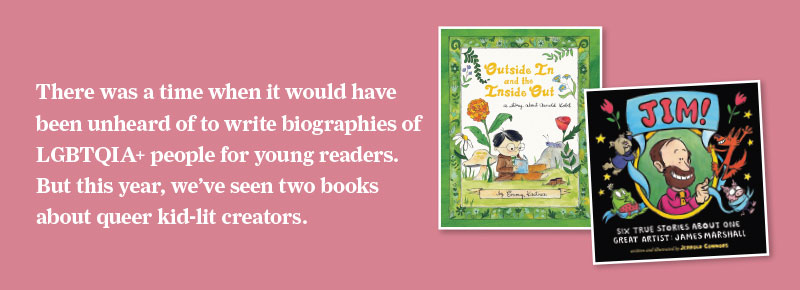

Social mores also change. There was a time it would have been unheard of to write biographies of LGBTQIA+ people for young readers. But this year, we’ve seen two books about queer kid-lit creators: JIM! by Jerrold Connors , about picture book artist James Marshall and Outside In and the Inside Out by Emmy Kastner, about Frog and Toad creator Arnold Lobel. Both books make clear their subjects were gay men in a way that the creators could not in their lifetimes, at least in public. They also open the door for other queer biographical subjects, like children’s book illustrator Trina Schart Hyman.

Not too tender for tough topics

When Carole Boston Weatherford was asked if there was any subject that has ever stumped her as an author of children’s books, she replies: “I have written about the doll test, the psychological study that proved segregation hurt Black children’s self-worth. I have written about the Tulsa Race Massacre, the worst incident of racially motivated hate violence in U.S. history. I have also written verse novels of Billie Holiday and Marilyn Monroe, both of whom were teenage victims of sexual assault.”

In other words, she has not been afraid to tackle tough topics.

In other words, she has not been afraid to tackle tough topics.

It can be difficult for the authors of adult books to do so, but it’s even tougher when writing for a young audience, from small children on up. Teens in particular have their reading choices heavily scrutinized.

“Teens are awash in information,” Fleming says, “but they have little context. My role, then, is to guide these young people through the bewildering sea of facts and contradictions to a place of clarity and understanding. Getting to that place may mean we’ll be sailing through ugly or unsavory historical moments. But that’s okay; I’m with them as their reliable guide. It is, in my opinion, preferable to leaving young readers to navigate the often disturbing waters of the internet on their own.”

For some, though, it’s a question of what is age appropriate. Is a young child ready to learn about the Tulsa Race Massacre? How much should an author say? What if an author leaves out pertinent information offering context and clarity?

“The last thing that I would want to do is have one of my nonfiction books spark a reader’s interest in a subject, only to have that reader’s pursuit of more information about the topic result in them feeling I had left out something that might fundamentally change their view on that topic,” says Chris Barton, who penned Glitter Everywhere, a book that considers both the good and the bad of everyone’s most beloved (or least favorite) craft supply. “I especially wouldn’t want readers thinking that I had left out that information deliberately, either because I couldn’t trust them to handle it or wasn’t skilled enough to figure out how to convey it to that audience.”

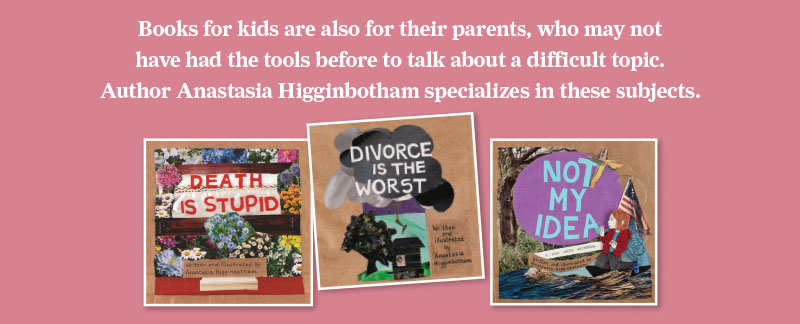

Books for kids are also for their parents, who may not have had the tools to talk about a particular subject. Anastasia Higginbotham specializes in these topics with titles like Death Is Stupid, Divorce Is the Worst, and Not My Idea: A Book About Whiteness. She says she has heard from readers who need her books the most. “A mother wrote to me on Instagram to say she shared Death Is Stupid with her son after his grandfather died. After they read it and talked, she said he went to sleep holding the book the way kids hold a stuffy or baby blanket, against his chest. And I felt 100 percent total fulfillment in life. There is no place on earth I want to be [except] in that boy’s experience of being consoled while he is missing his person. I have succeeded as a human to have made something that he can hold that close to his body.”

As Weatherford says, “Kids themselves are nuanced and complicated. They deserve and will demand the truth. We owe it to them to be honest and inclusive in chronicling history. Children are not too tender for tough topics!”

Laudable truths

Our children are growing up in a world in which basic truths can be distorted with ease. Avoiding difficult subject matter, including the lives of people who weren’t always saints, doesn’t help. It can delay knowledge until another source, possibly an inaccurate one, provides the information instead. Better that we take advantage of the wealth of great children’s book authors and researchers, and let them tell these stories in the best possible way.

“I think it’s truly possible to write about anything for kids if you have the right angle for them, keep their knowledge base in mind, always, and write from the heart,” says Deborah Heiligman, author of Torpedoed, about the sinking of the SS City of Benares, which evacuated children from England during World War II. “Topics have stumped me because I couldn’t find the story, not because I didn’t think I could write about them for kids.”

Children are not empty vessels. Many have already experienced the hurt, hate, and difficulties. Our natural desire to maintain a their innocence can be misplaced. As Marc Tyler Nobleman, author of another World War II nonfiction title, Thirty Minutes Over Oregon, says, “Learning [in developmentally appropriate ways] that bad things happen and people are flawed will not shatter their innocence. Rather, it will better prepare them for the realities of the world. In life, parents and other adults have to field questions from kids about matters from the unethical to the reprehensible. In literature, authors must find ways to do the same.”

There’s no better time to field those questions than now, with the best nonfiction books possible.

Betsy Bird blogs at “A Fuse #8 Production” (slj.com/fuse8).

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!