Silence Is Not an Option For These Student Advocates

Young people are speaking out and organizing to fight censorship and support issues important to them, making an impact in their schools, local communities, and at the state and national level.

|

|

Photo courtesy of Julia Garnett |

Julia Garnett never wanted to get involved. The high school junior disliked public speaking, and, as a competitive athlete, didn’t want to skip soccer practice.

But the 17-year-old couldn’t sit by silently while her school district, just outside Nashville, TN, considered a ban on A Place Inside of Me by Zetta Elliott—a picture book that deals with a young Black boy’s emotions after a police shooting.

“I went online and read it and was so confused about why it was going to be banned,” Garnett remembers. That night, in the fall of 2022, she wrote a speech defending the book. The next day, Garnett, accompanied by her dad, attended her first school board meeting.

When she arrived at the board meeting, Garnett didn’t even know where to sit. The room was so packed, people spilled onto the floor. A board member warned the crowd that police would remove unruly audience members, and before the night was over, a sheriff would escort out a woman behind Garnett.

“I saw so much division,” Garnett says. When it came time for her to speak, Garnett was terrified, but she knew what was at stake. This wasn’t about defending just one book from being banned.

“I fear that soon it will be extremely difficulty for marginalized communities in all levels of education to access books with diverse and inclusive themes and values,” Garnett told the board. “It starts with this book, but I ask you: What’s next?”

The board voted to keep A Place Inside of Meon the shelves thanks to the efforts of Garnett and other like-minded community members. And for the young advocate who never wanted to have to speak out, it was just the beginning.

|

SEAT’s Cameron Samuels (far left) and Ayaan Moledina (far right) joined fellow advocates King Ricky Rosè and Phillip Alexander Downie at the Supreme Court for the Rally for Inclusive Education in April.Photo courtesy of SEAT |

She is not alone. As books, curricula, and diverse voices are being censored, excised, and, in some states, even outlawed, Garnett and other young advocates like her are making themselves heard through walkouts and other protests, appearing in front of school boards and local legislatures demanding change, and turning to national groups for guidance and support. Their voices have come together to form a powerful chorus of resistance and movement to effect change across the country.

Garnett went on to become the first student member of her district’s review committee of challenged books. She discovered groups beyond her hometown and state, groups like the National Coalition Against Censorship (NCAC), that connected her with other youth advocates around the country and helped her develop the skills to speak to larger and larger audiences.

She is now an undergrad at Smith College in Northampton, MA, studying government and considering law school and a possible career in politics.

Finding their voice

In 2021, high school senior Cameron Samuels chose to speak up in front of their ISD school board in Katy, TX. The district had removed Jerry Craft’s New Kid from school library shelves and installed internet filters blocking students from accessing LGBTQIA+-related websites like the Trevor Project, a suicide prevention resource for young LGBTQIA+ people.

At the school board meeting, Samuels listened as adults spoke, reading parts of books out of context.

“It was fear-mongering and political rhetoric and I knew I needed to reflect that student voice,” says Samuels, who was the only student at the meeting. “It was really challenging to speak up at first because I was not a public speaker. I didn’t have confidence in myself and being in the public light.”

After they spoke, they returned to their seat while the audience sat in uncomfortable silence.

But Samuels was not alone for long. With the support of outside organizations like the ACLU and the NCAC, Samuels says, school board meetings filled with supporters, many wearing rainbow flags or holding up banned books.

That support inspired Samuels to found Students Engaged in Advancing Texas (SEAT), a peer mentor network that helps young people connect, learn advocacy skills, and take an active role in policymaking.

“Students are the experts of their lived experiences, and no one can tell us that our voices aren’t valid,” Samuels says. “We’re the ones in the classrooms every day experiencing the policies that adults make without us at the table.”

For many students, the first step is learning where that table even is. One of the most effective ways SEAT accomplishes this is by bringing students to the Texas State Capitol in Austin. That means arranging carpools and buying bus or even plane tickets for students coming from as far away as El Paso, an hour and a half flight from Austin.

Samuels has inspired many young people in Texas, including Ayaan Moledina, a 16-year-old high school sophomore who is now SEAT’s federal policy director. Moledina was only 10 when he decided he wanted to do something about the injustices that impact children and their lack of say in the matters.

“It’s all a blur to me,” he says when asked how a 10-year-old comes to that conclusion and sets off into advocacy work. “I do the best recalling what I can, but I say this all the time—this space chooses you. You don’t necessarily choose it.”

He never set out to be an activist, Moledina says, just to advocate and the work “spoke to me.” He is now working with and learning from Samuels.

“It’s an incredible honor to be able to work with Cameron,” Moledina says. “I’ve worked with a lot of leaders in my six years that I’ve been doing this—adults, young people, college students, high school students, everybody—and Cameron is by far the best.”

Moledina praises Samuels’s organizational skills, willingness to share the spotlight, and understanding the need to keep the organization from becoming a bureaucracy. Most importantly to Moledina, though, is Samuels’s willingness to try to find common ground with those who disagree with their opinions, to stand on their values and principles while also working to get things done, not just rail against an opponent.

With all of those leadership skills, and with the team built around them, Samuels heads a movement in Texas that makes an impact with unyielding efforts each day, focusing on the vital details, as well as large events. They expect around 250 students to join SEAT’s “advocacy day” this year at the Capitol. And Samuels and Moledina were part of an Inclusive Education rally outside of the Supreme Court on the day of the oral arguments for Mahmoud v. Taylor, a case about books with LGBTQIA+ characters and themes in public schools.

These are powerful moments, especially for Samuels, who has gone from standing in front of their school board alone to leading a student movement. Having just graduated from Brandeis University in Waltham, MA, Samuels is thinking about their next chapter, which will include studying public policy in graduate school.

As for SEAT, Samuels says the organization is ready for the next chapter of advocacy work as well. “We are ready for the challenge, and we’re equipped because of so many organizations which gave me that strength and support,” says Samuels, adding that they hope SEAT can do for younger students what other organizations did for them.

|

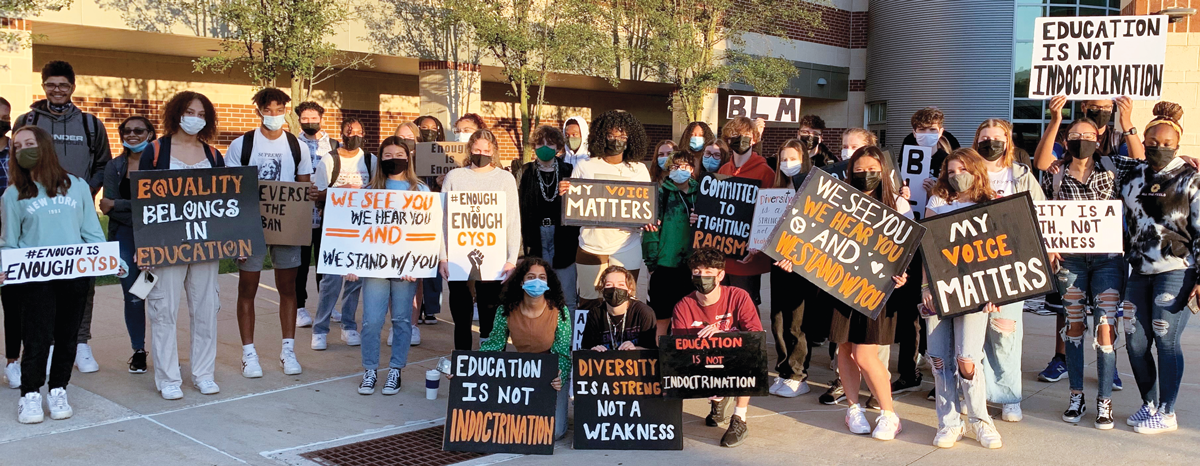

Students from PARU gather outside the Central York High School in August 2021 to protest the first book ban, which removed more than 400 resources by diverse authors.Photo Patricia A. Jackson |

Finding support

For students interested in taking on advocacy work in their school and community, there’s no shortage of resources available.

South Carolina’s Diversity Awareness Youth Literacy Organization (DAYLO) began in 2021 as a student-led book club in Beaufort, SC, in collaboration with the Pat Conroy Literary Center. In 2022, DAYLO student leaders responded when two community members challenged 97 books in school libraries, getting 91 books returned to the shelves.

Today, DAYLO has grown to roughly 150 members with 10 active chapters around the state, leading book clubs, community literacy initiatives, and anti-censorship advocacy. Most recently, 20 DAYLO students helped create a guide to youth advocacy toolkit that’s free for students around the country.

“Students spent a year building content based on our success and made it adaptable for students and communities,” says Jonathan Haupt, executive director of the Conroy Center and co-leader of the South Carolina chapter of Authors Against Book Bans. “We’re trying to share what’s worked well for DAYLO as a book club and as anti-censorship advocates.”

DAYLO has worked closely with other groups to build youth advocates from across the country, including SEAT and Pennsylvania’s Panther Anti-Racist Union (PARU). Launched as a club at Central York High School in 2020, PARU is led by faculty advisers Ben Hodge and Patricia A. Jackson. The group has fought book bans and other efforts to censor curriculum and has become a go-to source for other schools looking for advice.

|

DAYLO members speak with Nickelodeon’s Nick News at the South Carolina State House.Photo courtesy of DAYLO |

“A lot of districts are coming to us for help. We say you need to go on the offensive,” Hodge says. “We want what happened in our district and PARU to not just be a moment in time but a movement for other people around the country.”

This fall, PARU will release Ban This!: How One School Fought Two Book Bans and Won (and How You Can Too) , a guide the group hopes will inspire others and provide examples of successful advocacy.

“This format is exactly what’s needed for folks who don’t know what to do,” Jackson says.

Garnett and Samuels were both supported by NCAC. Founded in 1974, NCAC brings together nonprofits from around the country to engage in advocacy and education. For the last 20 years, the NCAC’s Youth Free Expression Program (YFEP) has empowered young people.

YFEP works with students, teachers, librarians, authors, and community organizers to oppose book censorship. One of its newest projects, the Student Advocates for Speech Leadership Program (SAS), trains the next generation of leaders.

Launched in 2022 with a cohort of 11 student leaders, SAS has since doubled in size; the program lasts about nine months, including summer training with partner organizations. Students learn advocacy skills, including public speaking and effective ways to write essays in support of free speech.

“We’re excited because these students come from across the country,” says Christine Emeran, director of YFEP. “They come with various backgrounds, but most without advocacy work, and we show them how to be effective.”

SAS also provides student advocates with a supportive community. While Julia Garnett was attending school board meetings in Tennessee, she didn’t find many other students with whom to connect over her advocacy work. That changed when she discovered SAS. “It sounded perfect for what I needed at that time, the broader support from students like me from all over the country,” says Garnett, who was selected as an SAS fellow in 2023.

The fellowship proved life-altering. Garnett and her fellow students met with legal experts and authors, and she learned how to further raise her voice, whether by giving radio interviews, writing testimony to the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee, and even interviewing author Lois Lowry about censorship.

During her senior year in high school, Garnett’s advocacy work included starting a Student Advocates for Speech Club that had 15 to 20 students working to protect access to books.

That year, she also was among 15 young women selected by the White House Gender Policy Council and recognized by First Lady Jill Biden during the “Girls Leading Change” ceremony. Garnett is now continuing her advocacy work at Smith College. Despite the challenges facing another generation of students, she’s optimistic.

“I have a lot of hope, and I think there’s less fear, less ‘I’m the only one doing it.’ That’s the main message. And students are seeing that in this beautiful way because of organizations like the NCAC,” Garnett says. “We’re getting better organized, and when you have this structure, and people have done this before —[you] can put [your] own spin on it, but there’s a framework to follow—that provides a lot of help to students who don’t know where to start.”

|

Krishnamurti (third from left) co-moderated a Young People Running for Office forum at the Harvard Kennedy School.Photo courtesy of Anjali Krishnamurti |

Impacting legislation

But students don’t want to just be heard. They also want a say in the policies that directly impact them. Moledina wrote a bill that would allow the board of trustees in certain school districts to create a nonvoting student trustee position on the board. The proposed legislation went to the Texas House of Representatives the last two legislative sessions. Still, without a vote in elections, there’s only so much power people under 18 can wield.

Anjali Krishnamurti wanted to change that. Growing up in a conservative New Jersey town, Krishnamurti witnessed several bullying incidents in her middle and high school that she thought were mishandled by her school board. But when she showed up to board meetings, all she heard was an “echo chamber of the same adults, some who didn’t even have children in the schools, and the things they were saying disregarded the experiences of young people.”

Even when she and other students began making their opinions heard, the 15-year-old realized there was a deeper, structural issue at play.

In her freshman year of high school, Krishnamurti cofounded Vote16NJ, a movement aimed at lowering the voting age to 16 in local New Jersey elections. In 2024, her work resulted in the Newark City Council approving an ordinance allowing 16-year-olds the right to vote in school board elections.

This past April marked the first election for newly registered 16- and 17-year-olds. According to the New Jersey Institute for Social Justice, about a quarter of eligible young voters registered, with 3.8 percent turning out to vote—surpassing the overall turnout of about 3.2 percent.

“There’s an argument that lowering the voting age to 16 will revitalize democracy,” Krishnamurti says. “It will create a lifelong habit to vote.”

The success in Newark isn’t the end of their campaign. Today, Vote16NJ has more than 50 active members working in 25 municipalities around the state. Krishnamurti, now 20 and a sophomore at Harvard University, says her career trajectory has largely been shaped by her advocacy work, and she hopes to eventually go to law school. “I’ve been inspired by the attorneys I’ve had the privilege to work with,” she says. “I want to study to be a civil rights lawyer and do work at the grassroots level.”

While still young, Krishnamurti and other student advocates who are now in college or close to graduating from high school have a wealth of knowledge to pass on to students just getting started in their own advocacy work.

Krishnamurti , who started Vote16NJ as a 15-year-old along with Yenjay Hu, says it was daunting at first, with most people telling her she was crazy. Then she spoke with Micauri Vargas, a lawyer with the New Jersey Institute for Social Justice, who advised the teens on how best to focus their actions.

Krishnamurti learned two important lessons that have guided her advocacy work ever since. The first is the importance of working with adults and tapping into intergenerational knowledge. The second, she says, is to be patient.

“It’s very easy, especially in youth organizing spaces, to be daunted by ‘no’s,’ ” Krishnamurti says, but she advises students to push through. “We were patient and overcame the ‘no’s.’ We got one ‘yes,’ and that’s what sparked the movement.”

Some young people might feel overwhelmed by the idea of launching their own organization, let alone speaking up at a school board meeting, but advocates say students can have an impact in small ways, too.

“Students don’t have to make a big speech or do something huge,” says Garnett. “There are so many ways to get involved and make change: emailing or calling your legislature, going to club meetings. If you’re not comfortable with speaking, just showing up and saying, ‘We’re here and listening’ is enough.”

Freelance education reporter Andrew Bauld writes frequently for SLJ. Kara Yorio contributed to this article

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!