Historical Accuracy in Illustration: Shifting Standards or Stubborn Certainties?

There’s been a lot of talk about accuracy in children’s nonfiction recently (which is just a fancy way of saying that there’s been a lot of talk on this particular blog). Everything from invented dialogue to series that are nonfiction-ish. One element we haven’t discussed in any way, shape, or form though is the notion of accuracy in illustration. And not just in nonfiction works but historical fiction as well.

My thoughts on the matter only traipsed in this direction because of author Mara Rockliff, as it happens. Recently she wrote me the following query:

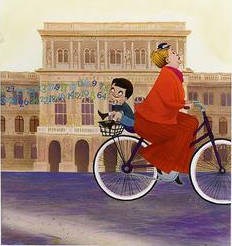

“One thing I wonder is why invented dialogue is so often the thing that bothers people most, while other issues don’t seem to come up. For instance, how do you feel about illustrations? It always seems to me that a historical picture book can never be strictly nonfiction, because no matter what the writer does, the illustrations will be fictional. I’ve got a couple of historical picture books on the way this winter. One has very fanciful, cartoony illustrations and the other has meticulously researched illustrations–but both are made up. If an illustrator says, ‘Well, this is the TYPE of thing Ben Franklin wore (but there’s no way to know what he wore on this particular day), and these are the gestures he MIGHT have made and the facial expressions he MIGHT have worn, and here is what his visitors MIGHT have looked like, and this is MORE OR LESS what they might have been doing at that moment, or possibly they never did anything like this at all, and this is a typical style for houses at that time…’ does that seem different to you from a writer saying similar things about invented dialogue?”

It is, you have to admit, an excellent point. Can illustration ever really and truly be factual, just shy of simply copying a photograph? Should we hold historical fiction and historical nonfiction to different standards from one another? She goes on to say in relation to made up text vs. made up art:

I’ve been struggling to formulate my thoughts on this, but I have a vague feeling that

(1) historical picture books should not invent IMPORTANT details (the main events of the story, for instance–what someone would say if asked to summarize the book), no matter how they’re categorized or what’s explained in the author’s note

and

(2) there should be clues to what’s made up in the story itself, both in the text and the art. Like, if the illustration style is cartoony and the dialogue is humorously anachronistic (“Your majesty, those colonists think they can beat your redcoats! Ha ha ha ha ha.”), an adult reader at least would assume the dialogue had been made up. I think.

There’s lots of time to chew on the notion of art in children’s nonfiction and historical fiction. Mara poses an excellent question about made up dialogue vs. illustrations. Why should one bother a person more than another? I think it comes down to the reality of a situation. Illustration is, by its very definition, going to be made up. The author might do more research than anyone else but you can never say for certain if an eyebrow was up at one moment or a person held a letter in that particular way another. So all illustration is supposition. Dialogue, however, when using quotation marks, is saying that a person definitely said one thing or another. If a books says, “This person may have said this or that” then they’re in the clear but when they use quotation marks without any caveats then they are saying a person definitely said one thing or another. Ex: “Put that peashooter down or I’ll kill you”, said Albert Einstein. When you read that you assume he actually said it. And, for whatever reason, that seems far worse than simply drawing him in one position or another. I think people will always assume that an illustration is coming out of the head of an artist, but wordsmiths are held to a different standard.

Now obviously even when we “know” that someone said something we can almost never “know” if they said that exact thing. But that’s where honesty comes in. Books that say right from the start that they don’t know one thing or another are being honest. Books that just lead you to assume that something happened the way they say it did are being dishonest.

Here in the library we always put “nonfictiony” books with fake elements in the picture book or fiction section. It’s a bummer but we don’t have much of a choice. I mean, compare a book like THE BOY WHO LOVED MATH which never ever includes any fake dialogue and makes a big deal about the fact that the illustration of the boy’s nanny is based on nothing because the artist couldn’t find a photograph of her (now THAT is honesty!) to a book which makes up fake people saying fake things for absolutely no good reason whatsoever. I really love books like HE HAS SHOT THE PRESIDENT that don’t rely on fiction to make the nonfiction parts good. Still, as long as there’s a caveat or explanation somewhere in there I’ll not raise any objections. But what about the art in HE HAS SHOT THE PRESIDENT? Why am I okay with illustrations that are suppositions and not text?

Here in the library we always put “nonfictiony” books with fake elements in the picture book or fiction section. It’s a bummer but we don’t have much of a choice. I mean, compare a book like THE BOY WHO LOVED MATH which never ever includes any fake dialogue and makes a big deal about the fact that the illustration of the boy’s nanny is based on nothing because the artist couldn’t find a photograph of her (now THAT is honesty!) to a book which makes up fake people saying fake things for absolutely no good reason whatsoever. I really love books like HE HAS SHOT THE PRESIDENT that don’t rely on fiction to make the nonfiction parts good. Still, as long as there’s a caveat or explanation somewhere in there I’ll not raise any objections. But what about the art in HE HAS SHOT THE PRESIDENT? Why am I okay with illustrations that are suppositions and not text?

Naturally I decided that this had to be a Children’s Literary Salon at NYPL. So as of right now we’ve a Lit Salon for March planned on this topic with Mara here as well as her HMH editor, Brian Floca, and Sophie Blackall. Let it never be said I go halfsies on these things. I’ll post a link to the event information a little closer to the date, no worries.

So what do you think? Is it ridiculous to your mind to distinguish between “reality” in art vs. text? Or could we go even further in the matter?

![]()

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!