2018 School Spending Survey Report

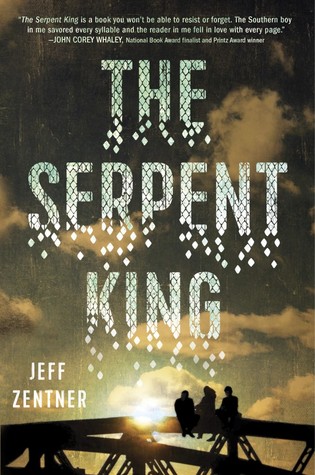

Snakes, Music, and Fashion Blogging: Jeff Zentner on “The Serpent King”

Nashville musician Jeff Zentner shares with SLJ what inspired him to write The Serpent King, a singular work about friendship, class, and having the strength to pursue your dreams and defy social impossibilities.

Photo by J. Hernandez

Nashville musician Jeff Zentner’s debut, The Serpent King (Crown, 2016; March 8), features elements that don’t often make it into a YA novel: a snake-handling preacher, a Tavi Gevinson–type fashion blogger, and class inequality. Here, the author shares with SLJ what inspired him to write this singular work about friendship, class, and having the strength to pursue your dreams and defy social impossibilities. What inspired you to write The Serpent King? A lot of things came together simultaneously to produce The Serpent King. First, my music career, in spite of what I thought were my best efforts, wasn’t progressing. Plus, I had crossed the age threshold for “making it” as a professional musician. So either I was going to have to settle for diminishing returns or try to change horses. Then I started volunteering with teens at Tennessee Teen Rock Camp and Southern Girls Rock Camp and got to experience firsthand how young people interact with the art they love. It made me want to create for that audience. But I didn’t think I could do it through music; I had to find another way. I’d always been an avid reader and loved writing, so I decided to try my hand at writing for young adults. I looked through my back catalog of songs I’d written, found two that I thought could be combined and expanded out into a novel-length story, dug up three character types I’d always been interested in writing about, and set to work. How did you come up with each of the characters and their individual story lines? Each character represents a certain type of person with whom I had become fascinated. From my time playing music in Murfreesboro, TN, I became intrigued by rural kids who used music to escape oppressive small towns. I was interested in Tavi Gevinson and the teen fashion blogger phenomenon, wherein very young people were joining national conversations on art and culture in a powerful way. I was interested in these fantasy-obsessed, blue-collar country boys you run into now and again in the South. I could have written a book about any of them, but I didn’t have the patience to wait for them to occupy three separate books. So I tossed them all in the same book and said, “y’all be friends, ‘kay?” A big part of the novel is focused on Dill’s family’s religious beliefs. Did you do a lot of research on Pentecostal religious practices? I was raised in a pretty strict religious home (not Pentecostal; certainly not snake-handler), so I understood from my own experience a lot of aspects of Dill’s upbringing. The rest I gleaned from reading and firsthand accounts from friends who had attended services at snake-handling churches. One nice thing about Dill’s religious sect is that his dad (and therefore I) invented it, so I had liberty that I otherwise wouldn’t have had if Dill were, say, Roman Catholic. What kind of research did you do on fashionista blogs (for Lydia), epic fantasy (for Travis), and incarcerated parents (Dill)? I used Twitter and Instagram to develop Lydia's sensibilities and voice. Those social media networks are a tremendous resource. I used Tavi Gevinson’s blog, Rookie, as the model for Lydia’s. For Travis, I’m a huge Game of Thrones fan, and I researched the series’ fandom. And, for incarcerated parents, I visited Nashville's Riverbend Prison several times. I didn’t really talk with anyone whose parents were incarcerated; I just sort of intuited that out, but I’ve since heard from people who have incarcerated parents that I got it right, so I’m glad. Much of the novel hinges on whether Dill decides to go to college or not. A lot of YA and media in general often takes for granted that college is an automatic next step after high school. Why did you choose to explore and zero in on that conflict? Because it was a natural outgrowth of Dill’s dire economic circumstances. There is an America where college is a given and always a choice for kids. There’s also an America where college isn’t just a financial impossibility but a social impossibility. There are pressures to quit school and help provide for the family. The latter America gets a lot less play in popular culture generally. I wanted to write a character for whom nothing about America’s promise is a promise. This work focuses on other topics that we often don’t see in YA: poverty and class. Why did you want to write about these facets of teen life? I was a teenager in a very different America from the America teens are growing up in today. There was far less awareness of increasing income inequality and the disappearance of the middle class. But these are issues our country is currently facing and that young people now will inherit. I wanted to write a story that reflected an America of haves and have nots. I believe that income inequality is one of the greatest dangers confronting [us]. I lived for years in Brazil, where income inequality is immense. People live like lords or paupers (at least in the area where I lived and during the time I lived there. Ironically, I believe Brazil’s middle class is now thriving and growing). It’s not healthy for a society to have such inequality of standard of living and opportunity. In The Serpent King, the rural Tennessee feels like its own character—from the train tracks to country music and Confederate flags. How did you decide what part of Southern culture to include? The South is a complex place with a difficult history that it’s forever wrestling with and atoning for its sins of the past. I incorporated as much about the South that I love as I possibly could (the landscape, the smells, warm people, the food, train tracks, and country music) while also making clear that the area still struggles with its legacy (Confederate flags and towns named after the founder of the KKK). Readers are presented in this book with all kinds of families—the kind that you’re born into and the kind that you make for yourself. Why is this an important topic to explore in YA? Sometimes even the best, most loving, most well-intentioned families can’t fill a young person’s needs. I grew up with wonderful, loving parents. However, there was only so much they could understand about me and relate to me, and so I needed a family network outside of them to get by. I think this is a common experience among young people. Under the best of circumstances—which not everyone has—your real family can only go so far and help so much to get you through the pain of adolescence. You have to find people who are going through what you’re going through. You’re a musician, like Dill. Is this work semiautobiographical? Sure, absolutely. Music is an important refuge for Dill as it was for me during dark times in my life. He writes songs on an acoustic guitar like I do. Yet Dill’s quest of using music to find new life as his old life is coming to an end is more similar to my writing journey than my musical journey. What are you working on next? I’m working on ideas for a third book. My second novel, which is done but doesn’t have an official, revealed title yet, will be due out in spring 2017. It’s not a sequel or a companion to The Serpent King, but it will feature a cameo from one of The Serpent King gang.

What kind of research did you do on fashionista blogs (for Lydia), epic fantasy (for Travis), and incarcerated parents (Dill)? I used Twitter and Instagram to develop Lydia's sensibilities and voice. Those social media networks are a tremendous resource. I used Tavi Gevinson’s blog, Rookie, as the model for Lydia’s. For Travis, I’m a huge Game of Thrones fan, and I researched the series’ fandom. And, for incarcerated parents, I visited Nashville's Riverbend Prison several times. I didn’t really talk with anyone whose parents were incarcerated; I just sort of intuited that out, but I’ve since heard from people who have incarcerated parents that I got it right, so I’m glad. Much of the novel hinges on whether Dill decides to go to college or not. A lot of YA and media in general often takes for granted that college is an automatic next step after high school. Why did you choose to explore and zero in on that conflict? Because it was a natural outgrowth of Dill’s dire economic circumstances. There is an America where college is a given and always a choice for kids. There’s also an America where college isn’t just a financial impossibility but a social impossibility. There are pressures to quit school and help provide for the family. The latter America gets a lot less play in popular culture generally. I wanted to write a character for whom nothing about America’s promise is a promise. This work focuses on other topics that we often don’t see in YA: poverty and class. Why did you want to write about these facets of teen life? I was a teenager in a very different America from the America teens are growing up in today. There was far less awareness of increasing income inequality and the disappearance of the middle class. But these are issues our country is currently facing and that young people now will inherit. I wanted to write a story that reflected an America of haves and have nots. I believe that income inequality is one of the greatest dangers confronting [us]. I lived for years in Brazil, where income inequality is immense. People live like lords or paupers (at least in the area where I lived and during the time I lived there. Ironically, I believe Brazil’s middle class is now thriving and growing). It’s not healthy for a society to have such inequality of standard of living and opportunity. In The Serpent King, the rural Tennessee feels like its own character—from the train tracks to country music and Confederate flags. How did you decide what part of Southern culture to include? The South is a complex place with a difficult history that it’s forever wrestling with and atoning for its sins of the past. I incorporated as much about the South that I love as I possibly could (the landscape, the smells, warm people, the food, train tracks, and country music) while also making clear that the area still struggles with its legacy (Confederate flags and towns named after the founder of the KKK). Readers are presented in this book with all kinds of families—the kind that you’re born into and the kind that you make for yourself. Why is this an important topic to explore in YA? Sometimes even the best, most loving, most well-intentioned families can’t fill a young person’s needs. I grew up with wonderful, loving parents. However, there was only so much they could understand about me and relate to me, and so I needed a family network outside of them to get by. I think this is a common experience among young people. Under the best of circumstances—which not everyone has—your real family can only go so far and help so much to get you through the pain of adolescence. You have to find people who are going through what you’re going through. You’re a musician, like Dill. Is this work semiautobiographical? Sure, absolutely. Music is an important refuge for Dill as it was for me during dark times in my life. He writes songs on an acoustic guitar like I do. Yet Dill’s quest of using music to find new life as his old life is coming to an end is more similar to my writing journey than my musical journey. What are you working on next? I’m working on ideas for a third book. My second novel, which is done but doesn’t have an official, revealed title yet, will be due out in spring 2017. It’s not a sequel or a companion to The Serpent King, but it will feature a cameo from one of The Serpent King gang. RELATED

RECOMMENDED

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!