2018 School Spending Survey Report

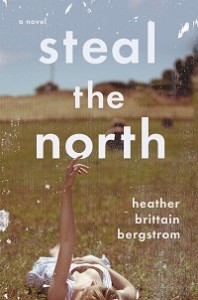

The Debut: SLJTeen Talks with Heather Brittain Bergstrom, Author of 'Steal the North'

Adult Books 4 Teens reviewer Diane Colson digs into Heather Brittain Bergstrom's debut novel, Steal the North, rich in imagery from eastern Washington, Indian reservations, and Baptist fundamentalism. It's a love story, not only for characters Reuben and Emmy but for anyone who finds themselves missing the place they once ran away from.

Thank you so much. I did indeed start with one story line: Emmy’s. I envisioned this novel as the story of a young girl on a journey to steal back her birthright—the North—from both her parents. It was to be above all a tale of reclamation. And believe it or not, when I first began, I planned to narrate the entire novel in just Emmy’s voice. That didn’t last long! Reuben was always going to be a character, of course, but I certainly didn’t plan to narrate in his voice. He jumped off the back steps of his sister’s trailer and insisted I let him tell his own story. As a narrator, Reuben brings a whole culture to his chapters and a richer, more complex look at eastern Washington. He also adds a story line of a son struggling to come to terms with his father’s life and death. There are other story lines that involve the adults, making Steal the North just as much a family saga as it is a love story. Two families merge, two cultures. But in the end, it is Emmy’s heroic act that closes the novel. She takes possession of her own life, and, by doing so, she steals the North (and, spoiler alert, she literally steals North with Reuben in his truck). This novel incorporates many of your own life experiences, doesn’t it? For example, you write with a deep appreciation of the Eastern Washington landscape. That appreciation took a long time to emerge. As a teenager, I couldn’t wait to get the heck out of eastern Washington—to escape the miles of sagebrush and basalt cliffs. And I did escape only days after graduating from high school. Before I tried my hand at a novel, I wrote short stories for years. In my stories, the characters are usually desperate to leave eastern Washington. It wasn’t until I had been away from my homeland for a decade or more that I began to miss it. I realized how much, like it or not, I had been shaped by the landscape of my childhood. I had left it, but it had not left me. Returning for visits, I began to see beauty where before I only saw ugliness. I had to accept the starkness of my homeland, and once I did, the place captivated me. I longed for the coulees, the wind, and even the sage. Emmy is my first fictional character to yearn for eastern Washington. Hers is the first migration north, rather than south. Reuben’s story tells much about feelings of Native Americans living on reservations in the 21st century. Perhaps most poignant is the pride and the shame he feels about his people and their traditions. Can you tell us how you were able to capture these feelings? Reuben’s chapters practically wrote themselves. They were the easiest in the book, when perhaps they should have been the most difficult. It really did feel as if he, not I, were telling his story. That being said, I grew up between the two largest Indian reservations in Washington State: the Colville and the Yakama. Grand Coulee Dam divides my home county from the Colville Reservation. I was born in Moses Lake, WA, a town named after Chief Moses, whose descendants live on the Colville. I went camping and fishing as a child on the rivers and lakes that border the reservation. People and place names such as Okanogan, Tonasket, Methow, Chewuch, Wanapum, Klickitat were easy for me to pronounce. Native Americans are very much part of the area where I grew up. As an adult, I have done intense research for a decade on Native Americans of the Pacific Northwest. I have also returned to the Pacific Northwest the last three summers to do research on various reservations in Oregon, Idaho, and, in particular, eastern Washington. The legends that explain the land originated in their languages. Their spirits continue to linger, as Chief Seattle warned whites, everywhere. I sensed these spirits as a child. You just had to listen. I’ve always been a listener. And I’ve always been an observer. Too often people think of Indians as relics from the past. My novel shows them as they are nowadays: kids in high school, struggling with algebra and playing football; health-care worker; dancers at powwows; riders at rodeos; teenagers cruising in trucks and eating gas station nachos; old people waiting at medical centers; all ages drumming at churches; elders wearing Nikes and praying beside creeks for the salmon to return. In the novel, Beth, Matt, and Kate express very different feelings about the teachings of the a fundamentalist church. Are these drawn from your own youthful encounter with Baptist fundamentalism?

Thank you so much. I did indeed start with one story line: Emmy’s. I envisioned this novel as the story of a young girl on a journey to steal back her birthright—the North—from both her parents. It was to be above all a tale of reclamation. And believe it or not, when I first began, I planned to narrate the entire novel in just Emmy’s voice. That didn’t last long! Reuben was always going to be a character, of course, but I certainly didn’t plan to narrate in his voice. He jumped off the back steps of his sister’s trailer and insisted I let him tell his own story. As a narrator, Reuben brings a whole culture to his chapters and a richer, more complex look at eastern Washington. He also adds a story line of a son struggling to come to terms with his father’s life and death. There are other story lines that involve the adults, making Steal the North just as much a family saga as it is a love story. Two families merge, two cultures. But in the end, it is Emmy’s heroic act that closes the novel. She takes possession of her own life, and, by doing so, she steals the North (and, spoiler alert, she literally steals North with Reuben in his truck). This novel incorporates many of your own life experiences, doesn’t it? For example, you write with a deep appreciation of the Eastern Washington landscape. That appreciation took a long time to emerge. As a teenager, I couldn’t wait to get the heck out of eastern Washington—to escape the miles of sagebrush and basalt cliffs. And I did escape only days after graduating from high school. Before I tried my hand at a novel, I wrote short stories for years. In my stories, the characters are usually desperate to leave eastern Washington. It wasn’t until I had been away from my homeland for a decade or more that I began to miss it. I realized how much, like it or not, I had been shaped by the landscape of my childhood. I had left it, but it had not left me. Returning for visits, I began to see beauty where before I only saw ugliness. I had to accept the starkness of my homeland, and once I did, the place captivated me. I longed for the coulees, the wind, and even the sage. Emmy is my first fictional character to yearn for eastern Washington. Hers is the first migration north, rather than south. Reuben’s story tells much about feelings of Native Americans living on reservations in the 21st century. Perhaps most poignant is the pride and the shame he feels about his people and their traditions. Can you tell us how you were able to capture these feelings? Reuben’s chapters practically wrote themselves. They were the easiest in the book, when perhaps they should have been the most difficult. It really did feel as if he, not I, were telling his story. That being said, I grew up between the two largest Indian reservations in Washington State: the Colville and the Yakama. Grand Coulee Dam divides my home county from the Colville Reservation. I was born in Moses Lake, WA, a town named after Chief Moses, whose descendants live on the Colville. I went camping and fishing as a child on the rivers and lakes that border the reservation. People and place names such as Okanogan, Tonasket, Methow, Chewuch, Wanapum, Klickitat were easy for me to pronounce. Native Americans are very much part of the area where I grew up. As an adult, I have done intense research for a decade on Native Americans of the Pacific Northwest. I have also returned to the Pacific Northwest the last three summers to do research on various reservations in Oregon, Idaho, and, in particular, eastern Washington. The legends that explain the land originated in their languages. Their spirits continue to linger, as Chief Seattle warned whites, everywhere. I sensed these spirits as a child. You just had to listen. I’ve always been a listener. And I’ve always been an observer. Too often people think of Indians as relics from the past. My novel shows them as they are nowadays: kids in high school, struggling with algebra and playing football; health-care worker; dancers at powwows; riders at rodeos; teenagers cruising in trucks and eating gas station nachos; old people waiting at medical centers; all ages drumming at churches; elders wearing Nikes and praying beside creeks for the salmon to return. In the novel, Beth, Matt, and Kate express very different feelings about the teachings of the a fundamentalist church. Are these drawn from your own youthful encounter with Baptist fundamentalism?

Credit: Michelle Chandler

Absolutely. I grew up in two different Baptist churches, the second one being far more fundamentalist. As a female, I couldn’t wear pants. We had no TV, secular books, or radio. Like Kate, I went to an unaccredited Baptist school, where many of the teachers, including my mother, hadn’t even finished high school themselves. Girls were taught sewing instead of science. It was a very repressive environment, particularly for females. In my novel, Kate gets the brunt end of this repressiveness. She is shamed and shunned. A segment of our church didn’t believe in going to the doctor for any reason. My parents, thank goodness, weren’t part of this segment, but I have some haunting memories of suffering women. However misguided, the church, in particular the less fundamentalist one, gave my family a needed sense of community. Eastern Washington is an isolated place. The overall population is small. On top of that, the landscape can seem empty, overwhelming, and even indifferent. In the church we had a large extended family. I still love some of those church members dearly, although I’m not in touch with any of them. My characters, Beth and Matt, are partly a reflection of that abiding love. I believe teen readers will be captivated by the love story of Emmy and Rueben. They both grow so much during their time together. Did you sense the potential for teen interest as you were writing? I wrote for an adult audience. However, there are a few scenes in which Reuben’s and Emmy’s adolescent tendencies seem to dominate so strongly that I found myself wondering if teenagers might be more interested in the angst and drama than adults. I fear if I would have written this novel with teenagers in mind, I may have become too didactic (which is never a good thing). I have a teenage son, and I never really wrote with him or his friends in mind. I have a daughter and a sister who are both in their 20s, and I certainly saw their age group as potential readers. I think as we get older, we get understandably more jaded and perhaps it is harder to believe in young love. But Emmy and Reuben’s romance is not an easy one. They both had to fight hard for it. They are both quite battered as they attempt to make their way back to each other. To wax didactic for a moment, I hope teen readers see the heroism in Emmy when, in the end, she takes possession of her life (not as a teenager, mind you, but as a young adult). Many kids nowadays have hovering parents. I am guilty. Kids struggle now more than ever to spread their wings. Before Emmy can begin her own life journey, she has to stand up to her mother. In the end, she does not throw herself at Reuben, but rather she picks him as a partner for this new journey toward self-possession and choice. Can you tell us what you are currently working on? I am currently working on a second novel. It is similar to Steal the North in that land is important and love is central. But the characters in my new novel are already misbehaving more than the characters do in Steal the North, so I think forgiveness will play a much larger role.Diane Colson is a Library Associate at Nashville Public Library

RELATED

RECOMMENDED

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Richard Moore

I keep noticing covers that draw from Wyeth's Christina's World. August Bank Holiday Lark is another.Posted : Jun 18, 2014 12:17