The Push for Police-Free Schools Continues Amid Debate

As schools look ahead to a return to "normal" this fall, advocates for police-free schools continue to push for community-driven strategies and restorative justice for student safety and overall well-being.

|

Students, educational organizers, and others at a learning exchange organized by the Communities for Just Schools Fund in Minneapolis.Photo by Tafari Melisizwe, courtesy of Communities for Just Schools Fund |

A few years after Branta Lockett became a teacher, an elementary student brought a $100 bill to school for the book fair.

“The student’s mother did not speak English, so I [sought assistance from] the school office to contact a parent at home to confirm that the child was supposed to have the money,” Lockett says.

As it turned out, the student was not supposed to have the money, so office staff informed the school’s dean, who spoke to the student and summoned security personnel to, as Lockett describes, “set the student straight.”

That was the moment when Lockett decided that police-free schools were a priority for her.

“I felt bad because that 8-year-old child had an encounter at school with a police officer for a matter that could have been handled differently,” says Lockett, now a program manager in Denver Public Schools.

Incidents like that one do not usually make the news. Instead, and understandably, television and social media are flooded with stark headlines about and horrific videos of school police inflicting violence on students.

However, numerous studies confirm that both violent and nonviolent encounters can have significant negative impacts on student well-being and future success.

“Research shows that young people who attend schools with police are less likely to graduate or enroll in college and are at increased risk of being ensnared in the criminal justice system,” says Meg Caven, senior research associate at the Education Development Center.

Caven, a sociologist who frequently examines social equity issues, also points out that “students of color are more likely than white students to attend schools with on-site police and are disproportionately impacted by police presence.”

Disproportionate punishment and related detrimental impacts, which stem from systemic racism and implicit biases, are key reasons why activists, educators, and advocates lend their voices and efforts to the movement for police-free schools.

The grassroots cause favors community-driven strategies to promote safety and the social, emotional, and educational welfare of students over policing. The movement is not new, but it gained national momentum after the murder of George Floyd in Minnesota last summer.

Since then and following numerous similar incidents where Black citizens died at the hands of white police officers, and subsequent nationwide protests, districts from Minneapolis to Los Angeles have voted to eliminate police from their schools.

But now, as educators grapple with students returning to school buildings amid the COVID-19 pandemic, communities are demanding social, racial, and educational justice. So questions abound as to whether police should return as well.

|

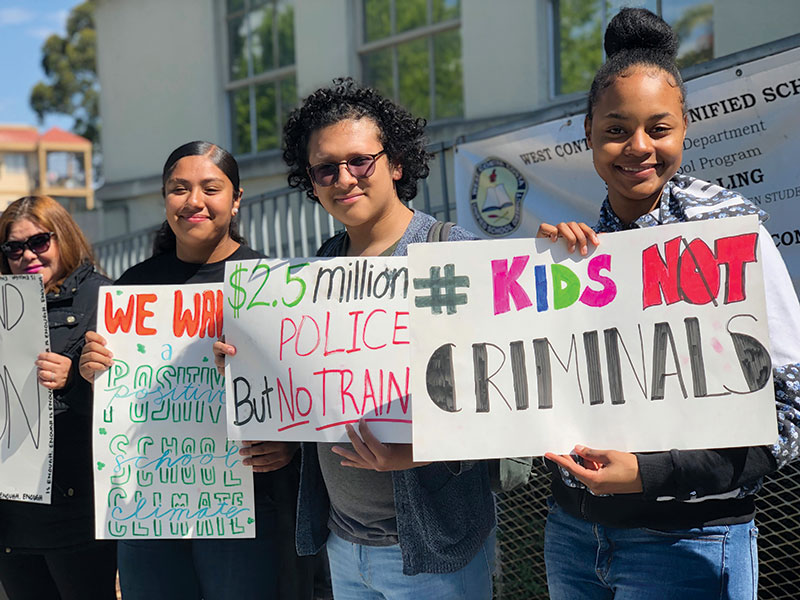

Students participating in an Our Turn Action Network protest (pre-pandemic).Photo courtesy of Our Turn Action Network |

Perspectives on safety

“The presence of police officers in schools is a threat to the safety of Black and brown youth,” says Jaime Koppel, codirector of the Communities for Just Schools Fund. The Fund is a donor collaborative that provides resources to grassroots organizers working for education justice.

Koppel points to physical, emotional, and psychological policing of people of color in the United States, which she says operates to maintain “centuries-old systems of injustice and oppression.”

Caven similarly notes that policing is tied to “artifacts of security and surveillance.” She spent time in schools where school resource officers (SROs) searched every student backpack and “ushered students through metal detectors every morning. Staff also routinely called the cops to search students who ‘seemed off’ in some way,” Caven says.

Caven believes that these and other “interactions with police and broader surveillance infrastructure instead tell students that they are suspects first.”

That is why, when the Communities for Just Schools Fund refers to “police-free schools, we not only mean getting rid of ‘the police’ the noun, but also ‘policing’ as a verb,” says Cierra Kaler-Jones, director of storytelling.

Whether the issue is police or policing, a common rationale for having sworn officers in schools is that they help keep schools safe. However, as Caven notes, “there is no research to support the idea that police make schools safer.”

This issue often arises in the context of school shootings. But research on the subject is mixed. Most studies have been hard-pressed to find an instance where a school police officer was able to intervene to bring an active school shooting to an end.

Similarly, while SROs establish a law enforcement presence, more children may be suspended or expelled or enter the criminal justice system, for relatively minor in-school offenses, according to a 2018 Congressional Research Service report.

Data from the Department of Education underscore that finding. Black students are reportedly almost four times more likely to be suspended from school and disproportionately more likely to be expelled than white students.

Additionally, the American Civil Liberties Union finds that in schools with police, it is nearly three times more likely that students of color will be pushed into the juvenile justice and criminal justice systems for minor school rule infractions.

“There is quite literally a pipeline that links schools to prisons, and it operates, at least in part, through school resource officers,” Caven explains.

|

Advocate and college student Salma Perez.Photos courtesy of Our Turn Action Network |

One way forward

Those stark impacts are part of the reason why, on June 24, 2020, Oakland (CA) Unified School District (OUSD) voted unanimously to eliminate its school police unit. The unit, which comprised sworn police officers and unarmed security personnel, had been in place for more than 20 years.

“There is no need for a school district to have their own police service,” says David Yusem, OUSD restorative justice coordinator.

Yusem says that police are often used as a de-escalation service when it is better for schools to rely on professionals who have expertise in mental health, such as social workers and therapists, who already have relationships with the students.

Going forward, OUSD will employ culture and climate ambassadors, who will welcome students and families, with a focus on positive community interaction. Ambassadors will also use positive behavioral approaches like mediation and conflict resolution.

In some cases, they may assist students who are returning to school from suspension or from the juvenile justice system. “Ambassadors will receive extensive training in de-escalation, trauma-informed practices, and restorative justice,” Yusem says.

OUSD began implementing restorative justice programs in its schools in 2007. Restorative justice focuses on building and maintaining strong community and relying on positive communication and roadmaps for accountability instead of unduly harsh punishment.

“When the community rose and demanded the police services be eliminated, many favored supporting restorative justice instead,” Yusem says. “Consequently, the restorative justice program at OUSD has been actively involved in rethinking how to keep the community strong, connected, and safe without police.”

Meaningful change?

Salma Perez, a college student, organizer, and activist, agrees that strong community connections and, in particular, student involvement are essential for achieving police-free schools. Perez works with Our Turn, a student-led organization that trains young people in organizing and advocacy.

“We students can bring about meaningful change by…recording experiences involving school police departments and calling forward student voice to help outline solutions,” Perez says.

Perez thinks that student voices are being heard in the current push for police-free schools but that more can be accomplished.

“If students remain engaged at every level of discussion—from the U.S. Department of Education to school boards in individual districts—we can create solutions that are specific to the needs of every community,” Perez says.

Teachers and educators can also play an integral role in bringing about positive change. Lockett finds that the teachers she interacts with seem to support removing police from schools. However, she has seen some pushback on social media.

“I think a lot of the resistance is a result of teachers lacking confidence in building relationships with their students,” Lockett says. “Some teachers fear the students or view them as adults and feel they need police to help de-escalate situations.”

Lockett is a member of Black Lives Matter 5280 in Denver. The group holds events around (and Lockett facilitates community workshops on) the “Counselors not Cops” campaign, which focuses on hiring more mental health providers for schools.

|

David Yusem, restorative justice coordinator for the Oakland Unified School District says that police are kali9/Getty Images |

“Counselors not Cops” stems from the fact that too many schools lack professional resources needed to support students. According to the ACLU, “14 million students in the United States attend schools with police but without a counselor, nurse, psychologist, or social worker.”

Denver Public Schools teacher Michael Diaz-Rivera agrees that “there is not enough funding for mental health and other resources to heal the harm that the community has experienced.”

He says that some of that harm was apparent to him when he “witnessed cops interrogating elementary students, harassing high school students, and refusing to come into the school without full armor.” However, he realizes that “[some] school leaders and staff…don’t want to let go of the friendly cop that they know.”

Caven offers a similar insight about students who have graduated and are reflecting on their high school experience. “There are folks who will tell you that their best relationship with an adult in high school was with the school resource officer,” she says.

Those connections to SROs and the belief that police in schools do some good may, in part, underlie a lack of understanding about the rationales for the police-free schools movement.

To help, Diaz-Rivera talks to community members and colleagues and participates in conversations with the SRO transition work group within Denver Public Schools. (Last summer, Denver schools voted to end its contract with the Denver Police Department.)

He believes that the most important thing educators can do in this moment “is challenge their personal ways of being and account for how that contributes to policing in the community.”

Though Lockett is hopeful that the current movement will bring about long-term change, Diaz-Rivera is not certain. Thena Robinson Mock, program officer for the Communities for Just Schools Fund, offers some perspective.

“History steadily reminds us that with great progress comes great backlash,” she says. Mock sees ongoing challenges for education justice organizers in terms of divesting schools from all aspects of policing and surveillance.

One of those challenges is that many districts have voted to keep police in their schools. Some have modified their contracts to provide additional protections for students, while others will not have resource officers wear uniforms or will consider having police remain outside school buildings.

In any case, as students return to school this fall, activists will continue to call for educational, social, and racial equity for all, which extends beyond individual district decisions.

“Organizations across the country remind us that policy changes do not guarantee the cultural transformation of schools the [police-free schools] movement is calling for,” Caven says. “That transformation requires careful planning and very intentional implementation of evidence-based approaches to cultivating positive school climate and safety.”

Kelley R. Taylor is a writer, journalist, and lawyer.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!