Tough Cookies Who Changed the Course of History | Nonfiction Booktalker

Here’s a recipe for stories with tough cookies: take one strong, intelligent woman, mix with adversity, add lack of opportunity and restrictions to education, pepper with patience and resolve, and the result is a flavorful story that will satisfy young readers. Tough cookies brought new perspectives to the table and changed history, and they make appetizing subjects for booktalks.

Here’s a recipe for stories with tough cookies: take one strong, intelligent woman, mix with adversity, add lack of opportunity and restrictions to education, pepper with patience and resolve, and the result is a flavorful story that will satisfy young readers. Tough cookies brought new perspectives to the table and changed history, and they make appetizing subjects for booktalks.

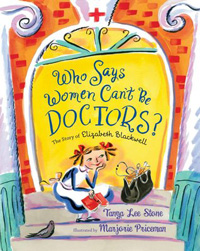

In the 1840s, Elizabeth Blackwell decided to become a physician after an ailing female friend confided that she wished she could have been examined by a woman doctor. Tanya Lee Stone’s Who Says Women Can’t Be Doctors?: The Story of Elizabeth Blackwell (illustrated by Marjorie Priceman; Holt, 2013) reminds us that this was unheard of at the time. Shocking! Horrifying! What was she thinking? Blackwell applied to medical schools and was summarily turned down by 28 of them. She was accepted by her 29th choice—the medical school in Geneva, New York. When Blackwell arrived for classes, she learned that her acceptance had been voted on by the male students, who thought the whole thing was a joke.

But Blackwell toughed it out. Eventually, she graduated at the top of her class, but still had to land a job, which proved just as difficult as getting into medical school. As Stone says, “Being a doctor was definitely not an option [for women]. What do you think changed all that?” Blackwell did, of course. Although intended for elementary school readers, you can also share this simple book with high school students who will be shocked by the obstacles that Blackwell had to face. Also, tell them that today more than half of all medical students are women.

Women had to be plain, strong, and unmarried to serve as nurses in the Civil War, Kathleen Krull tells readers in Louisa May’s Battle: How the Civil War Led to Little Women (illustrated by Carlyn Beccia; Walker, 2013). Thirty-year-old Alcott met those requirements. However, up until that moment, she had not succeeded at fulfilling her own prophecy, written at age 15: “I shall be rich and famous and happy before I die, see if I won’t!” An abolitionist, Louisa traveled to Washington, DC, to work in a hospital, tending to the Union soldiers who suffered horrible wounds and disfigurements. The experience lasted only a few weeks, but it changed her life forever. Alcott caught typhoid in the filthy hospital and was sent home to recover.

The future novelist continued to reflect on that period of her life, writing about it in her letters and her journals. She realized she could use that experience in her fiction writing as well. The first volume of Alcott’s Little Women, one of the first novels set during the Civil War, was published in 1868 and became a huge hit. “By the time Louisa was thirty-six, it made all of her dreams come true!” And by the time she died, the woman who had lived in poverty for most of her life was making the modern equivalent of $2 million a year.

Clara Lemlich couldn’t even speak English, let alone write it, when she arrived in America from Ukraine. Michelle Markel’s Brave Girl: Clara and the Shirtwaist Makers’ Strike of 1909 (pictures by Melissa Sweet; HarperCollins, 2013) tells the ultimately joyful story about the tiny immigrant who attended school at night, earned meager wages, and worked under ghastly conditions in a garment factory. Determined to change it all, Lemlich led a huge walkout of women workers, inciting them in her native Yiddish. While her male colleagues were afraid to follow suit, the young champion urged a general strike, which eventually enabled many workers to unionize.

When discussing these biographies, I urge my booktalk audience to do what I do when something intrigues me: dig in, investigate, and find out more. I discovered that Blackwell wrote about the various men she met. Lemlich lived a long life as a union activist, and when she entered the Jewish Home for the Aged in the 1960s, she encouraged the workers to organize. Although these informational books were written for younger children, they will pique the interest of readers of all ages.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Sharron McElmeel

Great list of books — and your suggestion to “dig deep, investigate, and find out more” is exactly what I did when I first read Stone’s “Who Says Women Can’t Be Doctors” and along the way I discovered Dr. Mary Walker — showcased in Cheryl Harness’s Mary Walker Wears the Pants: The True Story of the Doctor, Reformer, and Civil War Hero. Illustrated by Carlo Molinari. Albert Whitman, 2013. And then… as I delved further into Mary Walker I discovered that she had a connection to activism in IOWA — and better than just in IOWA, to my hometown area (Delhi, and Hopkinton, Iowa area). To view the results of that research go to the Iowa History Blogspot and search for Mary Walker - to find a page in Iowa’s History — Picture books can lead to so much more.Posted : Sep 05, 2013 09:17