We Need More International Picture Books, Kid Lit Experts Say

Betsy Bird. All photos courtesy of Guy Billout

“Wouldn’t appeal to children.” “[Kids] wouldn’t get it.” “Beautiful and depressing and downright weird.” These are the comments that SLJ blogger and NYPL youth materials specialist Betsy Bird has heard from fellow librarians when she showed them picture books originally published in other countries. Bird and others spoke about the importance of persevering in the quest to push these often unconventional books at “Where the Wild Books Are,” an event held at the New School in New York City on April 18 that celebrated these works and sought to determine why they encounter resistance in the United States.

Etienne Delessert, a Swiss illustrator, author, and publisher, decided to assemble the panel after reading a blog post by Bird in which she observed that, despite literary merit, books with a distinctly European look are often dismissed by her colleagues. His co-organizer was author/illustrator Steven Guarnaccia, currently an associate professor of illustration at Parsons School of Design. Featuring presentations from kid lit experts, a short film by the groundbreaking Indian publisher Tara Books, and a panel discussion moderated by Guarnaccia, the event drew several hundred attendees. “Kids...are asking millions of questions every day. I feel we should bring them books that are outside of [their daily experiences],” Delessert said.

Children’s books and American identity

Why do these books often go ignored in the United States? Children’s book expert Leonard Marcus kicked off the day with some historical context for the narrow outlook of American publishers and librarians. England had traditionally been seen as the “motherlode of culture by most Americans,” Marcus said. However, following World War I, the United States began to more actively forge its own cultural identity, an attitude that extended to the realm of children’s publishing. The Newbery and Caldecott Medals, established in 1921 and 1937, explicitly celebrate American authors and illustrators. While this national restriction made sense at the time, Marcus suggested that perhaps it’s time to revise the criteria for these awards and offer authors and illustrators from all over the world a chance. “It would give [American] publishers courage to look elsewhere [when acquiring books], knowing there would be financial payoff or publicity that comes to [one] that receives that recognition,” he said.

Bird agreed with the importance of looking beyond our shores and emphasized that everyone needs to be open-minded about international titles. “We’re all guilty,” she said. “We need to overcome this gross distrust of illustrations and topics that are literally foreign to our picture book shelves, and we all need to work on stamping out our own prejudices.” She added that children have greeted Belgium’s “Tintin,” Italy’s “Geronimo Stilton,” and England’s “Harry Potter” with open arms. “On the picture book side, kids love [works] that don’t originate here—if we let them,” she said.

Denise von Stockar

philosophical offerings

Several children’s literature experts examined noteworthy examples of what the panelist billed as “wild” European picture books—those taking novel approaches often absent from their American counterparts. Children’s literature expert Denise von Stockar described the publishing climate following World War II in Germany. Avant-garde illustrators began producing dynamic new work and publishing houses made risky choices, with highly original and groundbreaking results. She presented German and Swiss books that by U.S. standards take a dark turn, such as Helme Heine’s 1975 work The Secret of the Elephant’s Poohs, a “simple, even funny, highly philosophical” story that combines simple concepts such as numbers and scatological humor with high-level ideas, such as the idea of zero and death.

Similarly, Wolf Erlbruch’s profound and contemplative Duck, Death, and the Tulip (Gecko, 2011) centers on a duck who meets the grim reaper, ponders death, and eventually comes to term with her impending demise. Discussing French, Belgian, and Swiss artists, Christine Plu spoke about dynamic titles including Delessert’s inventively conceived How the Mouse Was Hit on the Head by a Stone and So Discovered the World (Doubleday, 1971), a collaboration between Delessert and legendary child psychologist Jean Piaget. While making the book, Piaget and Delessert consulted five- and six-year-olds, Plu said, tweaking their work based on the children’s responses.

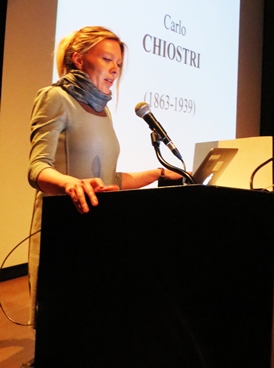

Giorgia Grilli

The Pinocchio legacy

Giorgia Grilli, professor of children’s literature and founder of the Center of Research in Children’s Literature at Bologna University, rounded out the discussion by focusing on Italian artists, touching in particular on different illustrated versions of Carlo Collodi’s The Adventures of Pinocchio. Though many Americans consider Collodi's original story an odd, even morbid choice for children—in one scene, two characters attempt to put the protagonist to death by hanging—in Italy, it’s a beloved classic that has been illustrated by renowned artists, from Piero Bernardini to Roberto Innocenti. Often, the weird or off-putting make for truly great art, Grilli added. “Mystery [and] strangeness lead to creativity. If Pinocchio had been a more obvious, simpler book...we wouldn't have had so many interpretations.”

Echoing sentiments expressed earlier, Junko Yokota, professor emeritus at Chicago’s National Louis University and a children’s book critic, who, via a pre-filmed PowerPoint presentation, spoke on Asian picture books, stressing that diversity is about embracing different formats and modes of storytelling as much as it is representation. “May the United States work on becoming a country to which the wild books are welcomed,” she said.

The day concluded with a panel discussion among Delessert, Enchanted Lion publisher Claudia Bedrick, and publisher and award-winning author and illustrator David Macaulay, moderated by Guarnaccia. In response to Guarnaccia’s question “What is a wild picture book?” Macaulay said, “Wild books are dangerous. They all question the norm and question complacency.”

Bedrick added that they are “books that are innovative and daring, both in image and construct and narrative...that help us see the world in different ways…[that are] diverse in terms of form and content and expression.”

(From l. to r.) Moderator Steven Guarnaccia, David Macaulay, Claudia Bedrick, and Etienne Delessert

“The American dream should be to have wild books”

Returning to the main question posed at the event—why there are so few wild books in the states?—Delessert cast the blame on publishers and the American attitude toward publishing. In France, he explained, independent publishers take financial and creative risks. In the United States, innovative thinkers don’t break out and establish their own companies, in his view: they head imprints at large publishing houses, where their decisions are often guided by marketing departments.

“The American dream should be to have wild books,” he said. “For many publishers, the American dream is to go to the bank.”

Some in attendance disagreed. Editor Neal Porter, whose eponymous imprint at Roaring Brook (whose parent company is Macmillan) produces many high-profile picture books each year, commented from the audience that “kids’ books are one of the few areas in our globalized world that remain culturally distinct. That’s not necessarily a bad thing.”

One of Bird’s final comments echoed the consensus: “We have to be willing to be made uncomfortable. That’s a really hard lesson, [but] the rewards [are immeasurable]. We need diverse books, sure, [but] we need international books.” “Wild Books” was supported by funding from the Cultural Services of the French Embassy, the Consulate General of Switzerland, and the Italian Cultural Institute, as well as the Creative Company and the New School.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Avery Fischer Udagawa

Increased sales (yes!) and high-profile awards in international picture books would be wonderful to see. As a translator, I often browse book displays in Asia and wish U.S. readers could see what I find. An infusion of translated picture books would not rob American picture book culture of its distinctiveness; rather, it would let readers enjoy a wide range of stories and modes, just as they relish an array of cuisines and musical styles. As children grow in a global world, they deserve access to the whole world's books‚ the "wild" and "weird" plus the warm, welcoming and wacky.Posted : Apr 30, 2015 04:19

Annette Goldsmith

Thank you for this summary! I would love to have been there. Though this stellar gathering focused on picture books, I would like to add that it's very important to have more translations and English-language imports for other formats too. I expect SLJ readers will already know about the USBBY Outstanding International Books (http://www.usbby.org/list_oibl.html), but I want to remind you all that this annual list of about 40 K-12 books is an excellent sampler of the year's best books from other countries. Also, in addition to advocating for more international books, we have to support publishers who DO publish international books by buying them for institutions and giving them as gifts. Sales speak volumes.Posted : Apr 24, 2015 01:21

Gregory Crocetti

Wow...it is so great to see people talking about our need to take new approaches to children's books - this event would have been truly amazing! A small group of Australian artists, scientists, writers and educators have started creating science-adventure storybooks for children and adults about microscopic partnerships in nature...and we don't pull any punches with our use of scientific language and concepts because we believe most kids can handle it better than we give them credit for. We have already launched two of our Small Friends books in the last year and are about to launch our first eBook in a few days time: http://www.smallfriendsbooks.com/squid-vibrio-moon/ cheers, gregory p.s. All downloads will be free in the first week of May!Posted : Apr 24, 2015 11:59

Alysa

I encountered those same comments (the ones that began this article) when discussing Hilda and the Midnight Giant with fellow Cybils judges. Except I don't think anyone said it was depressing. But, yeah! I think we grown-ups worry about giving kids weird books and we shouldn't. :) Weird (and sad and scary) things happen in kids' lives all the time. And dealing with the "other" in fiction helps you deal with it when it comes up IRL. I do think that adults should be gatekeepers for kids, and not permit lasciviousness or toxic books through the gate. But I don't think that whether or not adults think a kid would "get it" needs to be one of the criteria for keeping a book out. Sounds like it would have been really cool to attend this!Posted : Apr 24, 2015 07:59

Fran Manushkin

Don't other (older) countries than the U.S. have a darker view of life--one that's reflected in their books? The U.S. has always had a younger, more optimistic view of experience, as well as a less entrenched class system. Wouldn't this be part of the reasons why American publishers and readers resist "darker" stories?Posted : Apr 24, 2015 12:56