2018 School Spending Survey Report

New ALA Report Examines Licensing Model for Ebooks in School Libraries

For libraries, buying or licensing ebooks is a very different story than the average consumer simply clicking and purchasing off a book retailer website. A new report from the American Library Association takes a close look at the licensing models for ebooks, for school libraries in particular and how these policies affect access for students.

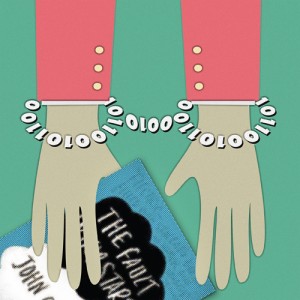

Consumers are familiar with downloading ebooks—they just click and buy. For libraries? It’s a very different story. A new report from the American Library Association (ALA) takes a close look at the licensing models for ebooks for school libraries in particular, with authors Christopher Harris (also a library director), Ric Hasenyager, and Carrie Russell asking how these policies affect access for patrons—namely, students. "The phrase ebook has a loaded meaning for the general public in that they have this impression that they buy the book on Amazon, and it goes on their Kindle,”says Harris, director of the school library system for the Genesee Valley Educational Partnership in New York state. “They don’t know what the problem is." Of course school libraries have a very different licensing requirement—which in some cases is slowing down the process for school districts looking to adopt materials for their schools, says Harris. Often titles are more expensive in digital format than their paperback copy for library editions, he says, which can be confusing to consumers who typically see the prices on Amazon for Kindle copies as cheaper than a printed version. Pricing is particularly hobbling many small school districts, says Harris, like his own. Often a digital content subscription is priced at a set fee for districts with unlimited access. The problem lies when you have a small school district in a rural area, as Harris serves, with just 1,000 students—a smaller population than the size of just one school in a larger, metropolitan area. (New York City’s Stuyvesant High School has 3,280 students, as an example.) “My school building with 200-300 students pays the same price as a school with 3,000 students,”says Harris. “Smaller, rural schools have less money, fewer resources, and they’re paying a higher percentage of their user costs for the same digital content.” Harris believes changes from the way publishers license to libraries could help school districts gain more access. One idea he floats is having small districts group together to collectively gain access to digital content—a move larger book publishers have currently said is not allowed, he says. Another is publishers allowing libraries to check out single titles simultaneously to a large group of patrons, rather than one title to one patron at a time. For example, HarperCollins allows libraries to check out a digital book 26 times and then shuts down access. Libraries however can only lend that book to one reader at a time. For popular books, say John Green's The Fault In Our Stars (Dutton, 2012), multiple students are likely to want to read the title at the same time, as the movie based on the book is out this month—but likely not next year. Allowing libraries to use their checkouts all at once—like a punch card—could help reduce costs as well.

Consumers are familiar with downloading ebooks—they just click and buy. For libraries? It’s a very different story. A new report from the American Library Association (ALA) takes a close look at the licensing models for ebooks for school libraries in particular, with authors Christopher Harris (also a library director), Ric Hasenyager, and Carrie Russell asking how these policies affect access for patrons—namely, students. "The phrase ebook has a loaded meaning for the general public in that they have this impression that they buy the book on Amazon, and it goes on their Kindle,”says Harris, director of the school library system for the Genesee Valley Educational Partnership in New York state. “They don’t know what the problem is." Of course school libraries have a very different licensing requirement—which in some cases is slowing down the process for school districts looking to adopt materials for their schools, says Harris. Often titles are more expensive in digital format than their paperback copy for library editions, he says, which can be confusing to consumers who typically see the prices on Amazon for Kindle copies as cheaper than a printed version. Pricing is particularly hobbling many small school districts, says Harris, like his own. Often a digital content subscription is priced at a set fee for districts with unlimited access. The problem lies when you have a small school district in a rural area, as Harris serves, with just 1,000 students—a smaller population than the size of just one school in a larger, metropolitan area. (New York City’s Stuyvesant High School has 3,280 students, as an example.) “My school building with 200-300 students pays the same price as a school with 3,000 students,”says Harris. “Smaller, rural schools have less money, fewer resources, and they’re paying a higher percentage of their user costs for the same digital content.” Harris believes changes from the way publishers license to libraries could help school districts gain more access. One idea he floats is having small districts group together to collectively gain access to digital content—a move larger book publishers have currently said is not allowed, he says. Another is publishers allowing libraries to check out single titles simultaneously to a large group of patrons, rather than one title to one patron at a time. For example, HarperCollins allows libraries to check out a digital book 26 times and then shuts down access. Libraries however can only lend that book to one reader at a time. For popular books, say John Green's The Fault In Our Stars (Dutton, 2012), multiple students are likely to want to read the title at the same time, as the movie based on the book is out this month—but likely not next year. Allowing libraries to use their checkouts all at once—like a punch card—could help reduce costs as well. “Why can’t I get 20 copies for the next two months and then not use it?” asks Harris. ”That’s the potential of digital content.”As for the potential for students—and other patrons—getting frustrated by lack of access to titles they want, and then skipping off to Amazon to just buy a book, or rent through a service like BrainHive, Harris is not too worried. “Libraries help you find the good stuff in all the noise,”he says. “Yes, Amazon has a recommendation engine, but is it the best book? Or a book they want to sell? And right now, I’m not sure, but maybe they’re not suggesting as many books from Hachette as they used to, for example.”

RELATED

RECOMMENDED

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!