Citizen Historians for the Smithsonian Is Creating a Digital Archive of Exhibits

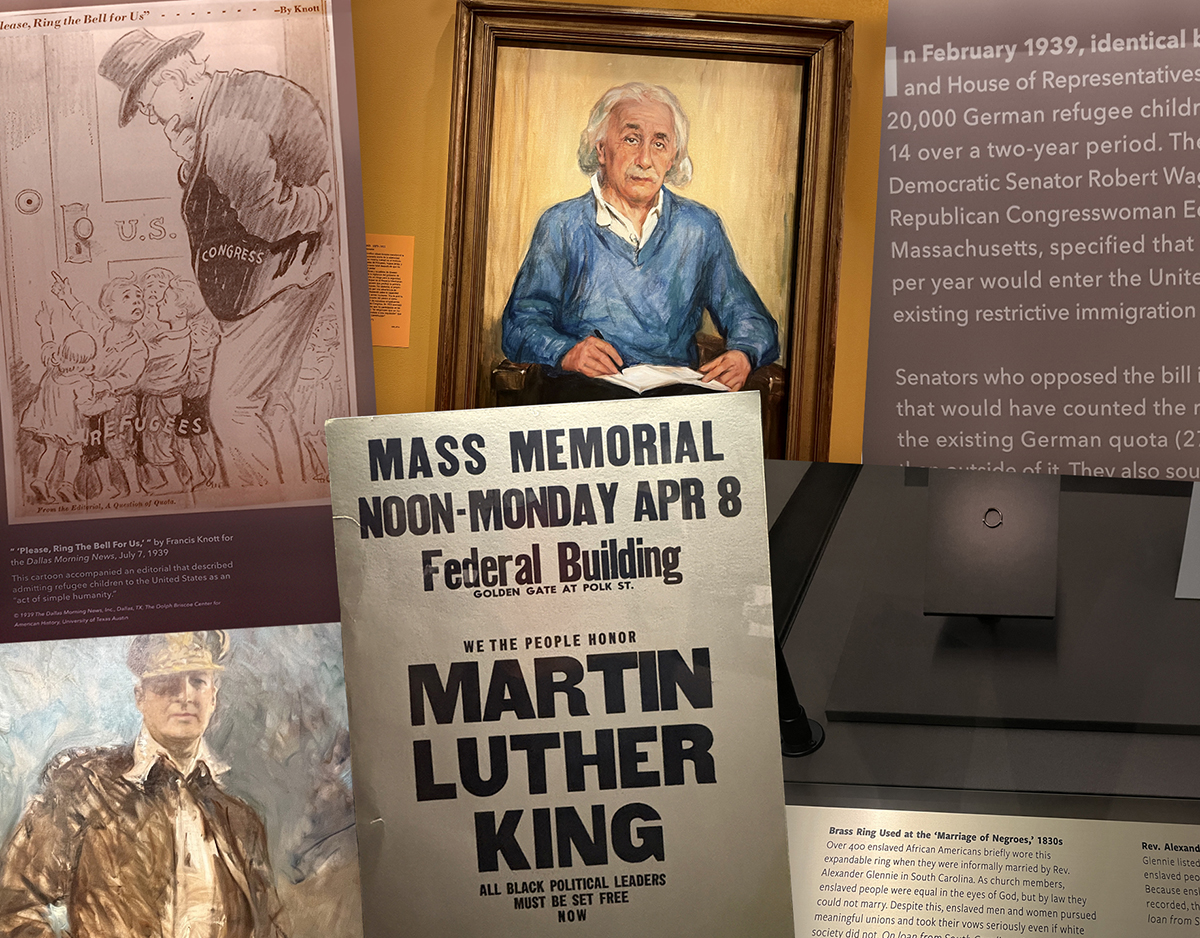

The all-volunteer initiative is documenting exhibits at the more than 20 Smithsonian Institution museums and the National Zoo in response to the Trump administration's announcement that museums' contents would be subject to review and revision to align with the president's directive.

When retired Virginia school librarian Mary Anne O’Rourke learned about a project to digitally archive the Smithsonian Institution museums, she immediately wanted to volunteer.

“I spent my career teaching children how to research and look up facts, how to know facts from distortions, and what were good sources? The Smithsonian has been our greatest source,” says O’Rourke, who was a preK–8 librarian for 11 years after being a classroom teacher and working at the Smithsonian Visitor Information Center.

Citizen Historians for the Smithsonian is an all-volunteer effort to document everything on display at the Smithsonian’s 21 museums, the National Zoo, and the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum. Volunteers take photos and videos of exhibits in this crowdsourced archiving endeavor. Organizers call it “Crowd to Cloud” and plan to make the information accessible to the media and public.

Citizen Historians for the Smithsonian is an all-volunteer effort to document everything on display at the Smithsonian’s 21 museums, the National Zoo, and the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum. Volunteers take photos and videos of exhibits in this crowdsourced archiving endeavor. Organizers call it “Crowd to Cloud” and plan to make the information accessible to the media and public.

The initiative is a response to an August letter sent by the Trump administration to the Smithsonian Institution secretary stating that exhibits were subject to review and revision in an effort to “reflect the unity, progress, and enduring values that define the American story.” The letter went on to say it was an effort to “ensure alignment with the President’s directive to celebrate American exceptionalism, remove divisive or partisan narratives.”

After learning of the administration’s intentions, Georgetown University history professors Chandra Manning and James A. Millward wanted to take action. Inspired by Save Our Signs—which seeks to document signs and information at National Parks that may be removed by the administration—Manning and Millward sent an email to the university’s history department saying they wanted to find a way to document the Smithsonian exhibits. Upon receiving the email, Jessica Dickinson Goodman, a graduate research assistant at the Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security, immediately proposed possible ways of achieving the goal and offered to help coordinate. Not only is the dual master’s student pursuing a degree in Global, International, and Comparative History, the Smithsonian also holds a special place in her personal history.

“When I was in college, my partner and I were long distance, and we would meet up every other weekend in D.C. and go to the Smithsonian,” Dickinson Goodman says. “They are very personal to me. They're a big part of my sense of my country, and my sense of my field, and my sense of pride in what it means to be an American—that we can produce these amazing free institutions to the public and to the world. And these institutions hold within them a huge amount of human wisdom and American and world experience that deserve to be accessible.”

Once Dickinson Goodman had the infrastructure in place, the three sent a wider email in search of volunteers. The response was overwhelming, and the progress has been swift. Since that first email was sent on August 21, Citizen Historians has more than 750 volunteers led by more than 20 volunteer captains, who each coordinate the documentation of a single museum.

In the first five weeks, volunteers took more than 31,500 photographs and videos and archived 56 percent of the Smithsonian exhibits. They are still looking for volunteers to take on the two Smithsonian museums in New York City—the Cooper Hewitt and the National Museum of the American Indian.

In training volunteer captains, Dickinson Goodman found that many people feel a special connection to the Smithsonian museums.

“The attacks on the Smithsonian have felt extremely personal,” she says. “I have spoken to captains whose loved ones dedicated their papers to a particular institution, and that is where their loved one’s handwriting and photos and voice recordings are held. I’ve spoken to volunteers who worked at the Smithsonian before retiring. This is their life’s work. I spoke to volunteers who, like me, had spent time with loved ones in them, or it was a core part of their care for this region. The Smithsonian institutions are very personal to millions of Americans and millions of people around the world. Attacks on their independence can feel very personal and be very motivating for people wanting to defend them.”

While O’Rourke did work at the Smithsonian years ago, her main incentive is preserving the history.

“I don’t think we should be afraid of our history,” she says. “It’s right there in front of us. We should learn from it. That’s what we want. We don’t want to change it and whitewash it because it makes some people uncomfortable.”

And she wants students to have quality sources of information and know which are trustworthy.

“If they come to distrust those sources, then where is their source? Where do they begin?” she says. “It can’t just be someone’s opinion. It has to be that we rely on the collective work of great minds.”

As a librarian, she would explain to her students the importance and value of a source like the Encyclopedia Britannica, which was “vetted and re-vetted,” not someone’s opinion. She doesn’t want younger generations to lose these valuable, objective resources.

“You don’t want to base the future lawmakers, the future decision makers, on opinion,” she says. “That’s why we have science. That’s why we have history to build on. Reality, not fantasy.”

A fellow former educator, retired Virginia high school math teacher Susan Stein, also read a news article about the Citizen Historians project and immediately wanted to volunteer. Documenting the exhibits is “necessary and gives me hope,” she says.

When asked why it was important for younger generations that the history be documented, Stein pivots to her experience with another wave of censorship impacting America’s youth. Even though she taught math, she had a large library at the front of her classroom for students who were finished with tests or homework. It included books she and her husband had read and loved or titles they thought young people would like.

“Quite a few books that I had in my personal library were the books they were banning,” Stein says.

Stein draws a direct line between losing access to books and removing materials in the Smithsonian. It’s censorship and the loss of access to information, an attack on intellectual freedom.

While they are still figuring out the exact details for the future, the end goal of the Citizen Historians for the Smithsonian project is public accessibility.

“My hope is that the Citizen Historians for the Smithsonian archive can serve as a resource for the general public, for journalists, and for historians who are seeking to see what these institutions look like at this moment in time,” she says, stressing that last point and the evolving nature of museum exhibits.

“These mediums are imperfect,” she continues. “They are the result of decades of scholarly work and the discussions that come from that. They are always evolving. Exhibits are always opening and closing. That is part of the regular, great chorus that is the Smithsonian Institution. If they are replaced by a single voice, we lose that broad wisdom and all of that shared history and shared truth.”

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!