From Creating Mini-Economies to Parsing Fictional Spending Scenarios, Here's How Librarians Teach Financial Literacy to Kids

April is National Financial Literacy Month. Libraries are doing their part to educate young people about concepts from budgeting to interest to help them be more economically resilient.

|

A student from Gloria Hicks Elementary School participate in the Minitropolis mini-economy.Photos by Bekah McNeel |

St. Louis media specialist Tom Bober’s elementary school book club read The Remarkable Journey of Coyote Sunrise this year, a popular middle grade novel by Dan Gemeinhart about a girl and her dad road-tripping across the United States on a school bus. The book is replete with themes to discuss, Bober says, but he made sure to bring one less obvious issue to the forefront with his students at R.M. Captain Elementary School. “How did they afford the gas?” he wondered aloud one day.

The students researched the price of gas along the characters’ route, determined the typical miles per gallon of a school bus, and worked out a budget for the road trippers.

Practical skills like these can make a huge difference in a young person’s quality of life as they take control of their own finances in their late teens and early 20s, according to a report from OECD, an international economic organization that advocates for financial literacy to be taught in high schools (bit.ly/2VNBKpf). Awareness of basic economic concepts, such as budgeting, debt, and interest, can help young people become more economically resilient and avoid predatory financial products as they build wealth.

Financial literacy doesn’t have to be isolated from other learning, as Bober, also a 2018 Library Journal Mover & Shaker, illustrates: Money affects nearly every aspect of life, and most of the stories we tell and read. School or public libraries can be ideal settings for kids to get attuned to money matters, through stories, displays, or targeted curricula.

Talking about budgets and financial realities in popular stories got Bober’s students thinking and added another dimension to the fictional characters they were reading about. “We started to get into some deeper elements of the story,” he says. For those who want to start delving into money matters with students, the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis has age-based reading lists with discussion guides rooted in financial literacy and themes. Bober has drawn similar concepts from other popular contemporary books so that students see the financial elements as even more relevant to their own lives. This is financial literacy instruction, Bober says—just not in the way people usually imagine it.

Library-based offerings

Financial literacy is an understanding of money and financial systems and how they work, so that people can make the most of the resources they have. With the rise of personal finance gurus such as Dave Ramsey and David Bach, financial literacy curricula have gained popularity for adults, and the same thing is happening in schools. Most states require schools to offer at least a half-year macroeconomics course for high school students. In 24 states, that includes at least one unit on personal finance within that course, according to a 2017 Champlain College report. Only five of those 24 states, however, mandate a stand-alone financial literacy or personal finance course, and none require it in elementary school. Still, as with other literacies—digital, civic, media—early exposure may be helpful.

A 2012 study from the University of Wisconsin-Madison Center for Financial Security found that between the ages of six and 12, students develop an increasingly complex understanding of how money works. Without direct instruction in school, the study says, children’s conceptions of personal finance are influenced by peers, parents, and media—all of which could offer misinformation. By high school, a Brookings Institution report found, many high school students are using credit cards and earning income. Those concepts have already become habits.

A 2012 study from the University of Wisconsin-Madison Center for Financial Security found that between the ages of six and 12, students develop an increasingly complex understanding of how money works. Without direct instruction in school, the study says, children’s conceptions of personal finance are influenced by peers, parents, and media—all of which could offer misinformation. By high school, a Brookings Institution report found, many high school students are using credit cards and earning income. Those concepts have already become habits.

Libraries have a potential role to play, Bober says: “I’m always looking at where I am going to add value.”

Because librarians interact with all of the children in the school, he added, they have a bird’s-eye view of what is being taught and how something like financial literacy might fit in. In his case, it has been a personal goal to weave it into discussion and research. A tech-focused librarian, however, might introduce budgeting software, and a library with a makerspace could include a budget component to help students understand the value of time and materials. Bober encourages librarians to work with teachers to open up opportunities for collaboration.

|

School Requirements: A Snapshot

In 26 states, however, it is solely up to school districts to decide whether to offer financial literacy classes, meaning that schools could operate similarly to the way they do in elementary and middle schools—providing financial literacy or personal finance through the library. Most states still focus on classroom instruction. |

A school-wide mini-economy

Librarian Andrea Martinez didn’t intend to be the primary driver for IBC Bank’s Minitropolis program at Gloria Hicks Elementary School in Corpus Christie, TX. The school’s administration adopted a school-wide miniature economy program, in which students hold school-based jobs, go shopping at stores on campus, and fulfill roles including minting cash (kindergartners), collecting taxes (first graders), and banking (fourth graders).

Only a willing administration could adopt such an intensive program, Martinez says. But after the principal and other administrators were replaced soon after Minitropolis launched, it fell to Martinez to keep it going. The initiative is coordination-intensive, she acknowledges—but there’s a lot of enthusiasm for it. All the Minitropolis activities are connected to what students are supposed to be learning according to the standards set by the Texas Education Agency.

Students are paid in “Jaguar Bucks” for their attendance, as well as for their school-based “jobs.” Some work in classroom retail stores, some are managers, some cut out money in the treasury department—all are paid accordingly. They learn that various jobs are paid differently, and they gain appreciation for the value of saving. The stores are stocked with donations of food, toys, garden supplies, and games from parents and local businesses. Some cost more than students can earn in a week; they also have to take taxes into consideration.

The goal is for students not only to manage personal finances, Martinez explains, but to understand their role in the larger economy. Helping each classroom set up part of Minitropolis has delayed Martinez’s plans for fully incorporating the library into the micro-economy. Students can already use Jaguar Bucks at the donation-based bookstore in one Minitropolis classroom. Those who choose to spend their money elsewhere can visit the school’s StarBooks Café, where peer readers share books, and students can use free Wi-Fi to access the school’s digital library from a café inside a classroom.

The library serves another purpose inside Minitropolis. Hicks Elementary uses a positive behavior intervention system, which reinforces pro-social behaviors by rewarding them with Jaguar Bucks. Earning the bucks is one privilege—using them is another. Shopping isn’t guaranteed, even if a student has Jaguar Bucks on hand. They must be good citizens of Minitropolis.

Those who have not earned shopping privileges can go to the library to discuss what went wrong. Martinez works with them on social and emotional skills—which involve self-regulation and relationship building—so they can fully participate in Minitropolis.

Online resourcesThe Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

|

A traveling library show

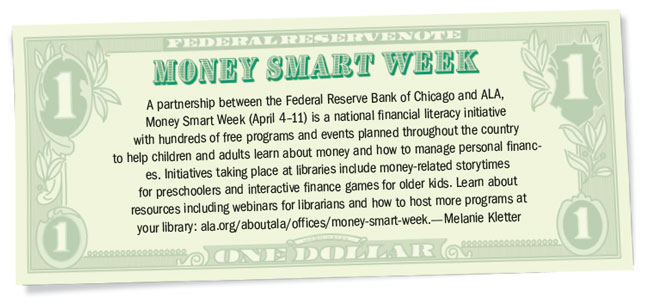

The American Library Association (ALA) promotes several resources for libraries to enhance their financial literacy offerings, including webinars, collection guides, and programming for those who want to partner with ALA and the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago for Money Smart Week (April 4–11). All of these have helped “open a dialogue” with patrons, says Lisa Fipps, marketing director at Kokomo-Howard County (IN) Public Library. Still, while learning about savings, credit, interest, and financial products is vital, Fipps says, “people don’t like to talk about money.”

The Kokomo-Howard County library system was one of 50 U.S. libraries selected by ALA to host a “Thinking Money for Kids” exhibit, which guides children ages seven to 11 through a series of finance-themed games and activities. The exhibit follows a story of earning, saving, spending, and sharing money through charitable giving.

The library team decided to expand the reach of the exhibit and align its seasonal activities calendar to financial literacy topics for the entire family. “The kids aren’t going to just come by themselves,” Fipps says, so the librarians created programs and classes for younger kids, teens, and parents at every branch.

The library hosted a kids’ flea market, sewing classes on how to redesign clothing, lunchtime sessions on credit scores and reports, and a make-your-own cleaning supplies workshop. “We tried to think of something for everyone,” Fipps says.

The earlier kids start understanding money and discussing it with parents, siblings, and teachers, Fipps says, the more likely they are to make sound financial choices for the rest of their lives. For students receiving financial literacy education, every effort pays off.

Bekah McNeel is a freelance writer based in San Antonio.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

At the elementary and middle school level, financial literacy runs on enthusiasm—that of librarians and students alike. While some middle schools adopt classroom curricula, most formal financial literacy instruction happens in high school. Once a state mandates financial literacy as a graduation requirement or component of high school economics, the content is usually delivered by a classroom teacher in the math or civics department. In Alabama and Virginia—both among those given an “A” in the Champlain College report—financial literacy is a mandated full-year course, with half the year devoted to personal finance. In other states—those given a “B” by the report—personal finance and financial literacy occupy anywhere between 12 and 63 percent of a macroeconomics course.

At the elementary and middle school level, financial literacy runs on enthusiasm—that of librarians and students alike. While some middle schools adopt classroom curricula, most formal financial literacy instruction happens in high school. Once a state mandates financial literacy as a graduation requirement or component of high school economics, the content is usually delivered by a classroom teacher in the math or civics department. In Alabama and Virginia—both among those given an “A” in the Champlain College report—financial literacy is a mandated full-year course, with half the year devoted to personal finance. In other states—those given a “B” by the report—personal finance and financial literacy occupy anywhere between 12 and 63 percent of a macroeconomics course.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!