Got Values? Then Live Them. It’s time for publishers to operationalize their ideals

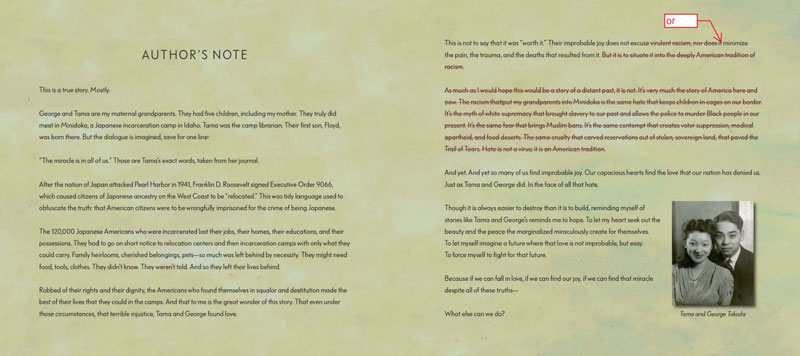

It’s some visual. The literal erasure of the word “racism” and by extension the lived experience of more than 100,000 Americans of Japanese ancestry and their descendants. Among them: Maggie Tokuda-Hall, author of Love in the Library—who received those amendments to her picture book by a Scholastic editor—and myself.

|

The author's note from Love in the Library with edits by Scholastic.

|

It’s some visual. The literal erasure of the word “racism” and by extension the lived experience of more than 100,000 Americans of Japanese ancestry and their descendants. Among them: Maggie Tokuda-Hall, author of Love in the Library—who received those amendments to her picture book by a Scholastic editor—and myself.

To omit aspects of history, “at a certain point, becomes not truthful,” says Lynn Yamasaki, director of education at the Japanese American National Museum (JANM), and a fellow descendant of the World War II incarceration of our parents and grandparents without due process. “If we take out the racism part of it, or if we take out the part where we link it to present-day events, then it’s really the most important part that we are removing.”

JANM condemned Scholastic’s effort to excise racism from Tokuda-Hall’s author’s note. “Censorship of American history has no place in literature. It smothers freedom of expression, erodes democracy, and contributes to historical revisionism,” stated Ann Burroughs, JANM president and CEO.

This time it was Scholastic. Yet fear-based, poor decision-making has occurred and is likely happening now across publishing. Even this case may not have seen the light of day if not for the editor, who spoke the quiet part out loud and in red ink, backed by an editorial letter expressing the same and, of course, Tokuda-Hall, who laid bare her pain, at some risk, to document her experience.

Read: SLJ's starred review of Love in the Library by Maggie Tokuda-Hall (text) & illus. by Yas Imamura

“They wanted to take this book and repackage it so that it was just a simple love story. Not anything that might offend book banners in this ‘politically sensitive’ moment,” she wrote in a blog post. “The irony of curating a [Scholastic] collection titled Rising Voices: Amplifying AANHPI Narratives with one hand while demanding that I strangle my own voice with the other was the perfect encapsulation of what publishing, our dubious white ally, does so often to marginalized creators. Always, our voices are the first sacrifice at the altar of marketability.”

It’s a lesson in self-censorship. You don’t have to be a bald-faced bigot to do damage. It’s the well-intentioned capitulators that will do us in.

Where do we go from here? I turned to diversity, equity, and inclusion expert Lily Zheng. “When companies don’t take a stance on issues—meaning systemic racism, injustice, inequity, sexism, transphobia, all of these—that means that their ability to take action on these issues is only as good or as bad as their worst informed decision maker,” they say.

The failure is not with this one person, Zheng maintains, but the lack of a system or process to operationalize an organization’s values. Talk to middle managers to learn what’s happening on the ground. Listen without judgment to illuminate what’s not working, then get granular on a dos and don’ts list. “We want our books to tackle tough topics of racism, sexism, transphobia. We want our editors to be able to recognize books that tackle this kind of content and approach it intentionally, critically, and helpfully,” posits Zheng. “If inclusion is a value, how do you act when you see exclusive behavior, inside the organization or outside of it?”

It’s rare that there’s a concerted effort at the top to be racist. But the end result is the same if Scholastic or any company doesn’t take a strong internal stand. While they may fear controversy or offending certain customers, there’s no playing both sides. “You can’t take no position and reap the benefit of it,” says Zheng. “You do need to take sides, especially in a climate that is seeking to ban books and teach ‘alternate’ histories. Any publisher is in this position of needing to defend, I’ll just say it—the truth.”

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!