Love Stories: Kate DiCamillo on the Hope, Humor, and Love that Fill her Books

Author Tae Keller speaks with DiCamillo about her latest book, Ferris, and the hallmark themes in her work.

|

Photographs by Joe Treleven |

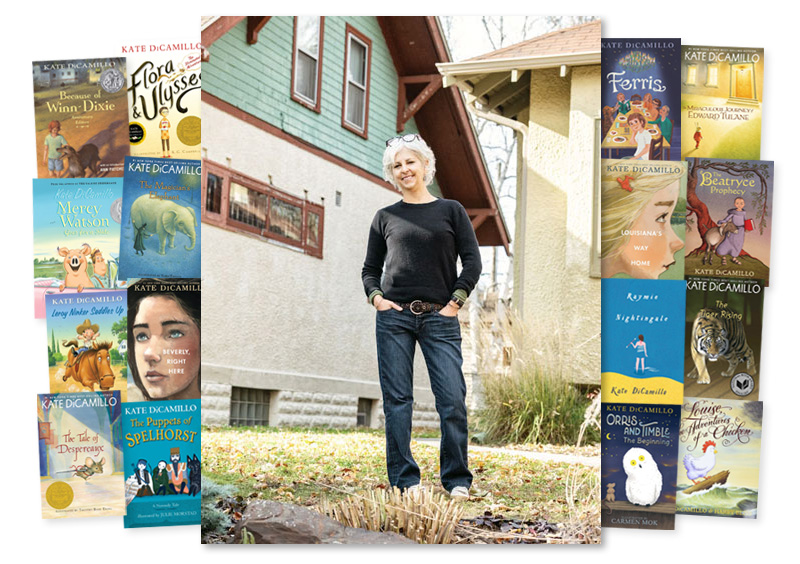

Kate DiCamillo hardly needs an introduction. The beloved author of Because of Winn-Dixie, The Tale of Despereaux, and Flora & Ulysses (all Candlewick; 2000, 2003, 2013) has two Newbery Medals and a Newbery Honor under her belt, and many of her books have been adapted for the theater and the screen. Most recently, Netflix released an adaptation of The Magician’s Elephant (Candlewick, 2009) last year. But even more impressive than her long list of accolades are her words themselves. Her books, filled with humor, honesty, and an almost aching kind of hope, have made millions of readers around the world feel less alone—me included. I was lucky enough to speak with her about her upcoming novel, Ferris (Candlewick, March 2024), a love story between a girl and her family, with all the trademark DiCamillo wit and charm. Here is an excerpt from our conversation.

Tae Keller: Before we start, I just have to say, I feel so grateful to get to talk with you, because obviously I love your books now, but I also grew up with them. I remember so vividly listening to The Tiger Rising in my fourth grade class, as a read-aloud, and reading Despereaux in my library period. It just feels surreal to be able to talk with you.

Kate DiCamillo: Oh, you’re making me tear up. This is such a good community, the children’s book community, because I remember when I got to talk to Katherine Paterson, and I was like, “I can’t even look at you!” Or when I got to hug Christopher Paul Curtis for the first time.

I just feel like we are a community of people all trying to do the same thing, which is to tell stories that make kids feel less alone and let them know that there is a way out and through. Life is hard, and I think that what we do is even more important now. And thank you, for the kid-you.

TK: Thank you. I mean, truly. Thank you for your work and for your words. I feel lucky to be in this long line of incredible people doing this work. I was gonna ask this at the end, but maybe let’s start here—thinking about how you started out, that version of you writing Winn-Dixie, if you could go back in time and say one thing to that person, what would you say?

TK: Thank you. I mean, truly. Thank you for your work and for your words. I feel lucky to be in this long line of incredible people doing this work. I was gonna ask this at the end, but maybe let’s start here—thinking about how you started out, that version of you writing Winn-Dixie, if you could go back in time and say one thing to that person, what would you say?

KD: I love that question. You know, it is so easy to put myself back there. Because I remember when I started on that story, I had this feeling, and even then, dull as I was, I kind of understood: “Oh, this is what I’m supposed to be doing.”

And so, what would I go back and say to that person? I would say: that feeling that you have, that this is what you’re supposed to be doing, is exactly right. I was filled with doubt—you know, I’m still filled with doubt—but it would be nice to go back there and say to that 30-year-old person, “This is it. This is what you’re meant to do.”

TK: Oh, that’s so lovely. As your career has developed, how have you found a balance between “the author” work and “the writer” work?

KD: I was doing an event last weekend, and during the Q&A, an adult raised their hand and said, “The Tale of Despereaux saved my life when I was a kid. How do you handle that—when people say that to you?” And I said, “I can’t think about it.”

My job, when a kid says something like that to me in a signing line, is to be absolutely present with them, to hear them and to tell them how much that matters to me. That, to me, is the extraordinary thing about a story. We can connect. And so, in the moment I want to be there for it. And then I want to forget about it, because otherwise it’s too unsettling. Do you feel that way?

TK: Yes. Especially with the responsibility of writing for kids. It can become paralyzing, almost, wanting to help them and be there for them, especially with the way the world is. How could you possibly write a story when you’re putting that kind of pressure onto one book?

KD: Right. And it’s also that thing of, you know, this happens so much in children’s books, where people say, “What’s the lesson?”

I don’t know adult writers who get asked that. And I always say, if I was trying to teach somebody something, I would fail miserably. And it’s the same thing here; if I sit down and think, “OK, now I gotta tell a story that’s gonna make a kid be able to live in the world,” I wouldn’t be able to do it. You can’t think about it.

I just did an event in DC, and it’s like, it’s overwhelming in the moment, and you have to be absolutely present for it—and then on the plane ride home, I read [Colson Whitehead’s] Harlem Shuffle and came back into my body.

TK: I love that you said you came back into your body. I’ve been feeling exactly that. In this separation of “author self” and “writer self,” writing always makes me feel like I’m coming back into myself.

In the vein of “the lesson,” I was thinking about vocabulary in your books. In Ferris, Ferris thinks about the vocabulary she learned from her fourth grade teacher, and she defines it for herself and for the reader.

Of course, your books are teaching kids this vocabulary, but I never get the sense that that’s why you’re doing it. And—sorry to quote you to yourself, but—there’s this one quote from the book that really stood out to me. When Ferris reflects on these vocabulary tests, you write, “Together, Ferris and Billy worked to memorize definitions and spellings for tests and tests. And in the process the words had lodged themselves permanently into Ferris’s brain and heart. They were hers.”

I thought that was lovely, and I was wondering, when was the first time you felt like words were yours?

KD: I was desperate to learn how to read, and when I got to school, I knew I needed story. I remember being just out of my mind to learn it.

And then they presented us with phonics. And for whatever reason, it was not the key to my brain. I was panic-stricken. I remember coming home from school and weeping to my mother because I was so desperate to learn how to read, and all these upside-down letters made no sense to me. This thing that I wanted so much was receding.

My mom, fortunately, knew my brain and was kind of this no-nonsense person who was like, “Well, for the love of Pete, there’s a way around it. You know you’re good at memorizing.” And she made flash cards for me. So I learned to read by memorizing the words, and every word that my mother held up to me felt like a gift, a key.

I have a flashbulb memory of sitting in the kitchen with her on the kitchen stools, and her holding those up and me thinking, “These are mine. This is it. This is what I needed.”

TK: That makes me think of what I felt was the backbone of Ferris, which is the line, “Every story is a love story.” The story that you just told is absolutely a love story, and it’s beautiful.

KD: It is, and you’re making me cry again. You know, I wish I had explicitly thanked her for that before she left. I knew a lot of what she gave me, but that was such a huge gift, because she saw so clearly what I needed, and she always took care of me as a reader. She was the one who got me books.

TK: Oh, it’s so important to have those people. I’m gonna call my mom right after this and thank her.

KD: Yes, thank her!

TK: That idea that every story is a love story—is that something you believed before you started writing this book? Or is that an idea you found as you were writing it?

KD: Can I say that you and I need to be friends, because I love the way you ask things—

TK: [silently dies of joy]

KD: My best friend, who I grew up with, her daughter had a child on the last day of 2019—December 31, 2019. And my dad had passed away in November of [that year]. December 31 was his birthday.

The pictures of this child, her name’s Rainy, rolled into my phone on New Year’s Day of 2020, and I just could not get over how loved this child was. There was her mother. There was her father. There were two sets of grandparents. And I just thought, “What would it be like if you started out that way?” You know, because it’s never where I’ve started a book.

And my father was so much on my mind because he had a miserable, miserable childhood. In all fairness to him, he tried to do better for us, and he didn’t. It was terrible.

And so, it was like, him leaving the world, her coming into it, and I thought, “What if I wrote a story about a kid that knew nothing but love, from the very beginning, from the moment she arrived?”

So that’s where I started. It was love, front and center.

And then—you know that thing of getting out of my own way—Charisse [Ferris’s grandmother] started saying that every story is a love story. The characters that I’m “inventing” are smarter than I am, because I think it’s true: every good story is a love story.

TK: I got goose bumps when you were telling that story. And I want to talk more about characters, because the characters in all your books are so larger-than-life, but they’re still so human—even when they’re not humans. And they’re quirky, but you never make them into caricatures. How do you approach building your characters?

KD: There’s not a lot of conscious thought for me as I find the characters. It’s more like they find me. And I know exactly what you mean about how I teeter right on the edge of them becoming caricatures, but I don’t know….

It’s that thing of, how can I say this, it’s like when people ask, “When are you gonna write a book for adults?”

And I always say, “I feel like I’m exactly where I’m supposed to be.” Because there’s always this kind of peripheral magic to me in children’s books, where you can kind of see the possibility out of the corner of your eye. Do you know what I mean?

It’s that Katherine Paterson quote, about how you’re duty bound to end with hope. And so these characters, who are so quirky and who show up unbidden as I’m writing, they’re real to me. And they’re part of that big journey toward hope, because hope can only exist when we see each other.

And that’s what books can do, make you feel seen and teach you how to see.

Tae Keller is the Newbery Award–winning and #1 New York Times–best-selling author of When You Trap A Tiger, Jennifer Chan Is Not Alone, and other books.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!