Lack of English Translation in Picture Book is a Lesson in Language and Communication

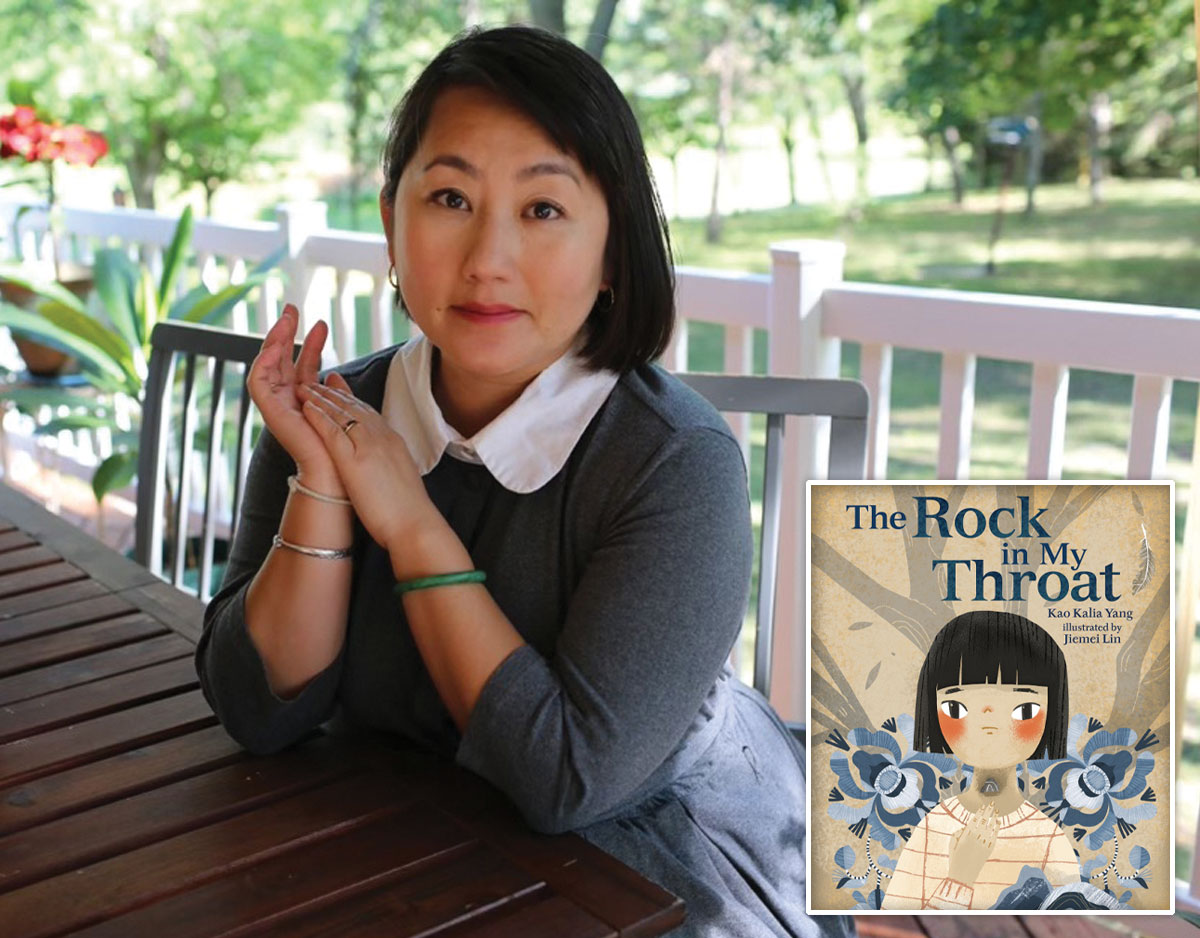

Criticism and misunderstanding of Kao Kalia Yang's decision to leave the Hmong-only phrases in her book, The Rock in My Throat, spotlights the problem of the English-dominant literary landscape in a country where residents speak hundreds of languages, the author says.

In the picture book The Rock in My Throat, I invite readers into the world of young Kalia. It is the story of a lonely child yearning for friendship and finding hope in the natural world. Through the incredible illustrations of Jiemei Lin, the America of my youth is resurrected.

I was a newcomer, a refugee child born in a refugee camp, who was experiencing this country, its culture, and its language for the first time. I was a child held closely by my loving Hmong family, yet in school and outside of our home, we were newcomers and strangers. We were small figures in big clothing that did not fit. We were soft voices in our language, struggling to be understood in the loud landscape of English.

In the book, as in my life, young Kalia stops speaking English after witnessing her mother’s attempts to be understood by an impatient clerk in a store. In telling this story, it was important for me to be deliberate and thoughtful about my use language to help readers engage with the experience of understanding—and not understanding.

In the entirety of the book, there are two lines written in Hmong.

My mother says to me, “Kuv tsis paub ua cas koj tsis hais lus tom tsev kawm ntawv.”

And I respond to her, “Kuv tsis paub thiab.”

These lines are not translated in the story. Instead, a reader who doesn’t speak Hmong must navigate them on their own, creating understanding from the context of the rest of the narrative. And when they reach the end of the book, they can learn the exact meaning of those sentences in the author’s note.

Some early readers and reviewers have read my decision not to interpret these lines on the pages where they appear as an oversight and a weakness of the book. They are not reading it as it is: a weakness of the English-dominant landscape that has silenced the multiplicity of languages that have lived, and continue to live, here in this country.

The United States of America has no official language. The people in this country communicate in more than 350 languages. These facts are important for children to understand, for the adults in their lives to teach them.

While accessibility in a picture book makes comprehension easy, it is the ways in which writers like me navigate moments when meaning is challenging that successfully teaches readers of all ages the valuable lessons about communication. In a book that is explicitly about my experience of a place where people didn’t understand me or the ones I loved most, making the translation of the Hmong phrases immediately accessible does not serve my readers.

As a writer, I feel it is my responsibility to offer the breadth and depth of my experiences, to put forth my truest self on the pages of my books, so that my readers, no matter what language they speak, no matter where their stories begin, understand that there is a place for them to be heard and understood. And sometimes that responsibility means challenging picture book conventions or upending an adult reader’s expectations.

As a child, I lived with a rock embedded in my throat because I could not articulate the reality of my experiences in a world that showed me time and again that it was not listening, that my words did not matter, that I was not part of the bigger whole, a critical piece of the puzzle, an essential feather in the flight of a bird, soaring high in search of beauty, of a gentler humanity. As an adult, my great hope for The Rock in My Throat is that readers will leave the book with a deeper understanding of not only this Hmong child and her mother, but of themselves as individuals and all of us as a community.

Kao Kalia Yang is an award-winning author of books for children and adults.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!