Louisiana Coalition Offers Model for Turning Back Anti-Library Legislation

The actions of this broad coalition of partners, led by the Louisiana Citizens Against Censorship and the Louisiana Association of School Librarians, lays out a template to follow in other states battling bad bills.

|

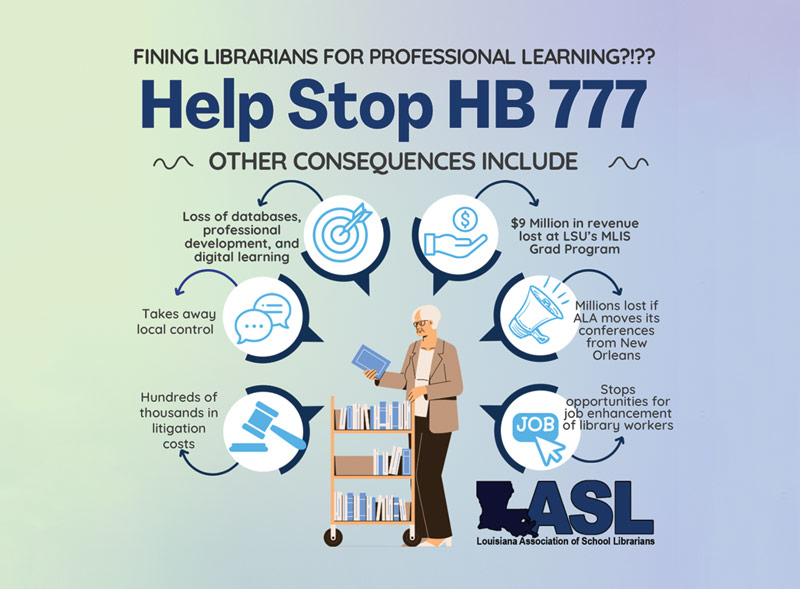

Image courtesy of LaCAC |

The fight for intellectual freedoím and protection of school and public librarians is being fought in state legislatures and courtrooms across the county. Building a coalition of library advocates is imperative to successfully battling the bad bills and public attacks. But what happens once partners are identified and on board? What exactly does a coalition do, and how can it meet its goals?

Library advocates seeking a model need look no further than Louisiana, where a coalition of groups led by the Louisiana Citizens Against Censorship (LaCAC) and Louisiana Association of School Librarians (LASL) defeated seven of nine anti-library bills in the last legislative session. Of the two that passed, one was amended in the library’s favor, so the library advocacy coalition ended up successful in eight of nine.

“It was a truly combined effort of public, academic, and school librarians, combined with the help from community members, parents, and other organizations, such as 10,000 Women of Louisiana, ALA, and EveryLibrary,” says Amanda Jones, LASL past president and a key member of the coalition. “We built a coalition of library lovers/supporters.”

This was the second year that LaCAC took on legislation—2023 was, as LaCAC co-founder Lynette Mejía calls it, “a flying-by-the-seat-of-our-pants situation.”

As they fought four bills in the 2023 legislative session, LaCAC created a letter-writing campaign and contacted representatives. When they got to Baton Rouge for legislative sessions, they learned that other organizations were also working toward defeating the bills, overlapping the efforts with their own letter-writing campaigns and testimony.

“We said, ‘This year, we need to have everybody on the same page with a unified strategy,’” says Mejía.

Creating a committed and formidable opposition to the legislation became more important as the nature of the bills became clear.

|

Lynette Mejía (left) and Amanda Jones led the coalition.Photos courtesy Lynette Mejía |

“This year, bills took a darker turn,” Mejía says of the legislation that included three that proposed criminalizing librarians.

The first step was to assemble a coalition of partners. For the battle against harmful bills in the 2024 legislative session, the LaCAC coalition included: LASL, Louisiana State University School of Library Science, 10,000 Women Louisiana, and the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, as well as current and former library board members and library directors from around the state, library science professors, and Louisiana Library Association members.

“Everyone understood the stakes and was willing to do the work,” says Mejía.

In March, coalition members met for the first time for a Zoom meeting. Among the attendees, a representative from EveryLibrary joined the call to share successful strategies for fighting anti-library legislation in other states. Those on the call discussed the bills and issues, each participant’s knowledge and strengths, and created a strategy and action items, assigning tasks where needed. Those action items were shared with advocates via a listserv and posted on social media. A spreadsheet with each bill and key information about it was kept updated.

In subsequent calls, coalition members discussed which bill was coming up in committee or for a vote and identified someone who could go to Baton Rouge to represent libraries and intellectual freedom advocates.

“Whenever I would go, I would say I represent citizens and patrons,” says Mejía. “Legislators really seemed to respond when actual librarians went. To see those faces and hear those stories had an impact on some of our legislators.”

Librarians made calls and some visited the various politicians involved with filing the bills in person, says Jones. But the librarians were not alone. “Several organizations with contacts to other legislators on committees would talk to those legislators. It was truly a team effort.”

There were Zoom calls every few weeks during the legislative season, but a Slack channel of the inner circle and coordinating members of the coalition was active every day. Members were given the talking points and priorities via email and listserv. LaCAC also posted an analysis and talking points for each bill on its website.

“We divided our arguments into tiers—which were the most important to hammer home—and based our talking points on those,” says Jones. “Then we’d gather as many people as we could to go and speak and share the tiered talking points. We encouraged people who were too nervous to speak to attend in solidarity and fill out cards of opposition.

“On the day of committee hearings, everyone would meet in the Capitol cafeteria or outside of the hearing rooms to go over talking points again together, and everyone would walk in and sit together. Most of the time, an effort was made to sit in the front rows for a show of force and solidarity.”

After each hearing or step in the bill’s process, Mejía and Jones would send out the outcome of that day’s events; a list of actions people could take, such as emailing or calling; and alert everyone to the next date for that bill. They used Linktree to consolidate the information. For each bill, they listed the next step for that bill, the date it was happening, and an action item that Louisiana residents could take. They pushed these updates via listservs and social media, and made a point to reach out to people on both sides of the aisle.

“We tried to get both Democrats and Republicans involved, to show this was an attack on the first amendment and an attack on our libraries,” says Jones. “We wanted to show that this should be a nonpartisan issue, and we pushed to spread the truth, and that truth is that there is no pornography in libraries, and these bills were not about books, but rather about devaluing and defunding libraries through a misinformation campaign and bad-faith legislation.”

For Mejía, the LaCAC work opposing the legislation became a full-time job—all day, every day. She knows that while others want to help, they don’t have the time or aren’t willing to make that effort. Someone from 10,000 Women of Louisiana suggested they use Action Network, which provides a website where people can generate letters to their legislator by filling in a simple form.

“Anything you can do that can make it easier for people to take action,” she says.

Every coalition organization had the same link to the same letter, instead of each organization sending its own letter, as they had in the past. The result was a mass movement felt by the representatives.

|

Amanda Jones (second row, in black) and advocates during a legislative session.Image courtesy of LaCAC |

More than 44,000 emails about the bills were sent over the course of the legislative session, according to Mejía. To her, that showed that people do care and are willing to participate in the process if someone facilitates it for them.

And the emails had an impact. It didn’t matter that they all used the same language, because legislative aides record whether constituents are for or against a bill—not the exact words used in the communication. Mejía heard the emails cited during committee meetings with members noting the number of emails they received that opposed to the bill.

But a letter-writing campaign doesn’t work if nobody knows about it, so another key component to the success in Louisiana was creating graphics for social media, including Instagram, Bluesky, Facebook, and X. Each graphic contained the bill number, key information, and how people could take action.

Jones created most of those social media assets. In an attempt to make it even easier—knowing people can’t click on a social media image and get to a website—LaCAC put the link to the site in the reply or comments section of the post.

At the same time they were getting word out to the public with the social media education and action campaign, they sought to educate legislators about the potential impacts of the bills. LaCAC created “one-sheets,” highlighting the key issues and possible consequences of the bills that they wanted legislators to know, and handed them the sheets before committee meetings. Coalition members also had as many conversations as they could.

“The main thing we learned was it’s really important to speak to legislators, if possible, one-on-one,” says Mejía. “It’s important to know which legislators are likely to be sympathetic to your cause.”

To help, they looked through related bills to see how the legislators voted and paid attention to comments during committee meetings.

Their efforts paid off. But even with the overwhelming victory this year, it’s unlikely to be the end of the legislative attacks on libraries in Louisiana. New attempts to revive previously failed anti-library bills have popped up elsewhere. In Alabama, where a bill to criminalize librarians for the content of their collections failed to pass this year, a similar bill was already proposed for the 2025 legislative session. Mejía expects the coalition to have to fight new legislation in her state next session, too.

“I do know that several of the legislators who put forth these bad bills are still fired up,” says Mejía. “They haven’t let it go.”

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!