Tiffany D. Jackson At a Crossroads | Margaret A. Edwards Award

In a deeply personal acceptance speech at ALA Annual in Philadelphia in June, the YA author discussed her life influences, racism in publishing, and professional uncertainty.

|

Photo courtesy of Tiffany D. Jackson |

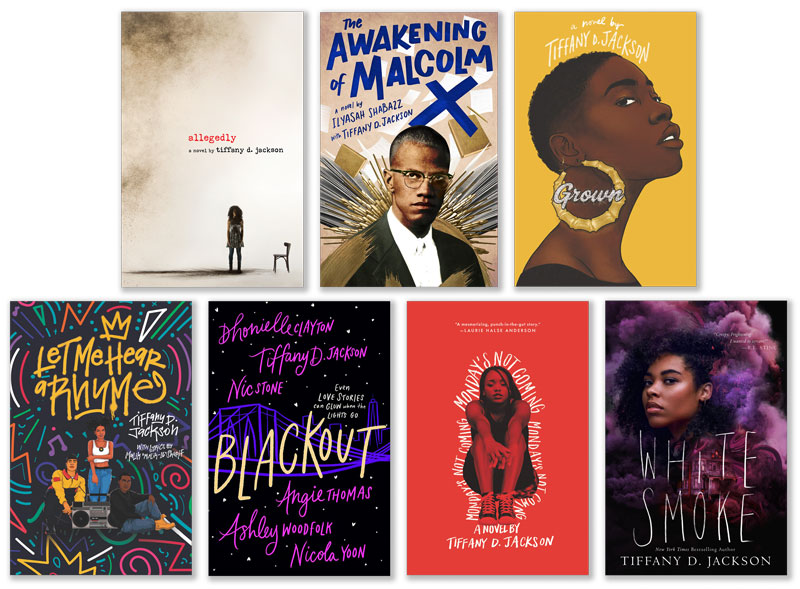

Tiffany D. Jackson won the 2025 Margaret A. Edwards Award “for significant and lasting contribution to young adult literature.” In a deeply personal acceptance speech at ALA Annual in Philadelphia in June, the YA author discussed her life influences, racism in publishing, and professional uncertainty.

Here is the speech in its entirety:

I’d like to thank ALA/YALSA and School Library Journal for recognizing my work. This an absolute honor of a lifetime. I’d also like to thank the Edwards committee. None of the members were able to make it to this year's ALA awards, primarily due to budget restraints and cuts. But their work here should be acknowledged and praised.

When I received the call that I was receiving this award, I was genuinely confused. I didn’t have a book out last year, and so I didn’t understand why they were calling, nor why they wanted me to jump immediately on a Zoom call. So, bless them for dealing with my funky attitude like the rest of my family and friends have to do, ‘cause I definitely hit them with a, “What do you want?”

My one-year-old at the time had a stomach bug, so I had been busy fighting for my life, with poop splatter on my shirt and my matted hair in a bonnet. I was in no condition to jump on anybody’s Zoom. But I did with my camera off, and they told me I won an award and honestly, it couldn’t have come at a better time.

After this award was announced, I got so many messages from colleagues, agents, and every single editor I’ve worked with.

“You are way too young for a lifetime achievement award, but this is a huge testament to your talent and your accomplishments! We are so proud of you, and so happy about this wonderful recognition!” -Rosemary Brosnan

“I promise, it’s not a lifetime achievement award. It’s a ‘wow, you’ve left a mark already, and there’s still plenty of time to make more marks’ award, and in that, you are exceptionally deserving.” -David Levithan

“Congratulations, Tiffany!!!! I hope you are swimming in the glory of the Edwards Award. I can’t think of anyone more deserving! I know you have your hands full with life and love. I hope that it balances out the hatred and bullshit that gets thrown at you.” -Laurie Halse Anderson

“Many congrats again on the Margaret Edwards Award. While I know your contributions are far from over, your body of work thus far deserves such glowing recognition. I’m grateful to have been a small part of it.” -Ben Rosenthal

“Just catching up on everything and see they’re sending your ass out to pasture. Congrats!” -Jason Reynolds.

This award is serendipitous for so many reasons. At the top of this year, I found myself at a crossroads in my career and life, with me being a new mom and the industry seeming to be heading in several different directions. And with the uptick of book banning and decrease of school visits, I was trying to decide if I wanted to continue being an author. If all my books were going to be banned no matter what I did, do I even belong in the YA space anymore? Do I have anything left to say? If I were to go home to glory tomorrow, would I have left a mark?

I recognize that there no one like me in this industry. And I'm not saying that to toot my horn or flex, I'm saying that because it's exhausting. It's an exhausting task paving your own way and defending your very existence in a white-saturated genre. When I first debuted, there were only three Black authors writing thrillers in all of YA. Before I wrote White Smoke, there were only two Black women writing horror in YA. I wish I could tell you how many times I was asked, “Why thrillers?” or “Why horror?” Why not? I didn’t see anywhere written that this genre belonged exclusively to white men. Or another questions I got often: “When are you going to write a happy book?” And after pointing to the several I have written, like Blackout and Whiteout and two picture books, I would follow up and say, “Do you ask Stephen King when he’s going to write a romance novel?” To quote mother Toni Morrison, “You can’t understand how powerfully racist that question is, can you?”

But I digress.

Still, I was used to the head-scratching questions. After all, I went from reading R.L. Stine to Stephen King and nothing in between at the age of twelve. I love thrillers and horror. I loved the breathtaking moments, the suspense, the tension, the danger. I was a quintessential ‘90s kids. Whatever books happened to be around the house, I would snatch up and read. James Patterson, Mary Higgins Clarke, Nora Roberts, Toni Morrison, Terry McMillan.

Let me step back and tell you about my favorite part of a book: the dedication. See, I think book dedications are one of the most priceless, beautiful gifts you could ever give someone. A gift that truly lasts forever. So let me share a few of my dedications and their inspirations:

First one: TO GOD. (God spelled capital G, a very large O, and a backwards D).

This was a dedication in a book I wrote when I was six years old. It was about aliens visiting my school in Brooklyn. It was made with construction paper, the freshest crayons, and a stapler, featuring stick-figure pictures. I always say, if given the chance, I could take Jerry Craft’s job like that.

I knew I wanted to be a writer since I was four years old. I distinctly remember practicing my handwriting in my room. I realized if I put letters together, I could spell a word. And my first word was “nose.” I looked at the piece of paper, out the window of the Brooklyn Clocktower, and said I was a genius. But back then, the idea of me being a writer translated to being a broke starving artist. And that wasn’t acceptable in my family, who clawed their way out of the projects, surviving immigration from Caribbean islands. Everyone did everything they could to deter such a life goal. But the thing about a dream is, when you ignore it, it turns into a nightmare. You will never truly be happy doing something you are not meant to do, and I tried for years to ignore what was burning in my fingertips. At first, I was going to be nurse, then I studied film. I worked in TV for fifteen years before I finally said, enough. And I honestly, through all the stress of the publishing industry, I’ve never been happier. The universe will never let you ignore the call of your destiny. You must be obedient to the call of a dream. Obedience is what turns dreams into reality. And I thank God every day for this amazing life.

The dedication Allegedly, my first official novel reads: For my mother and my grandmother, who never let me feel an ounce of pain.

Often times people have read my novels, and when they finish crying or throwing the book across the room, they often ask, “What happened to you? Why are you the way you are?” And nothing happened to me; I had a very happy childhood, albeit with plenty of bumps in the road. Growing up in Brooklyn during the ‘90s makes you an extremely resilient kid. But I was loved and raised by two incredibly strong women. And though they didn’t always understand me, they set the tone for excellence, for going above and beyond. It’s why I consider myself a method author. See, I didn’t just research about girls in group homes. I went into group homes, I interviewed doctors and lawyers, correction officers, then when that wasn’t enough, I interviewed five girls who’ve been through the JJ system. In fact, everything that happened to my main character Mary was something that actually happened to a girl I interviewed, including being raped in her prison cell.

My grandma was my heart; she was my everything. She looked and sounded like Maya Angelou; she was a poem walking. She also beat the hell out of me once for saying I hated books and I didn’t know how to read. I later found it because she was from a generation that wasn’t allowed to read.

When she was dying, I laid in the bed with her and watched her take her last staggering breath, listened to her heart stop.

I was twenty-six, and I don’t think I’ve ever been the same since that day. It turned me into stone. Like, you think you could hurt me? I watched my grandmother die. You think I’m scared of death? I watched my grandmother die. Death rearranges your brain. So maybe that’s why I can do what I do, without flinching. Maybe that’s why I can dig deep and write things that may make others uncomfortable, because I know on the other side of it, I’ll be okay.

Dedication in Monday’s Not Coming: For my Daddy and my Pop-Pop, who let me fly but were always there to catch me.

Before I became a full-time author, I worked in TV for fifteen gloriously messy years. Sometimes I worked seventeen-hour days, and in May of 2012, I was on a particularly dreadful shoot when my grandfather’s nursing home called. I ignored the calls, assuming they were just asking about his laundry or something to that effect. But when my shoot was done, I called my mother to say I still have work to do, but the nursing home called so did she talk to them? And that’s when she told me that my Pop-Pop had passed away twenty minutes before, while I was still unloading props out of a cab. He was a one-hundred-four-year-old Jamaican.

Two months later, when I was faced with criticism for my un-stellar performance at my job, all I could think was, you mean during that time my grandfather died, and I was doing the job of three people, but only getting paid for half a person AND didn’t take any days off to grieve? You mean during THAT time?!? Oh.

Something clicked in me that day. I knew that when I got to one hundred four years of age like my Pop-Pop, I wanted to look back on my life and know with unwavering certainty that I did everything I wanted to do. And all I wanted to do was write. That same week, I read an article that inspired my first book. Two months later, New York was hit with Hurricane Sandy, which had me trapped in Brooklyn with no internet or cable. But that idea kept rubbing at my temple, so I walked down the street to Brooklyn Public Library at Grand Army Plaza and wrote the first draft of Allegedly. That hurricane gave me a week off to work on my novel.

It’s a very scary thing, choosing yourself. As a woman, we’re not trained to be selfish. But when my grandfather died, it took any fear I had away and replaced it with gall.

Dedication in Grown: To the victims, to the survivors, to the bravehearted, to the girls who grew up too fast...we believe you.

In high school, my parents had the fantastic idea of leaving Brooklyn and moving to the suburbs, so I could get a good education. I hated that high school. There’s not enough time to talk about the damage of being a token Black girl in a white high school, but it ultimately prepared me to be a token Black girl in most spaces I entered. Still, I hated my school. It felt like no matter how hard I studied, I was still failing everything. I started having panic attacks, and I was desperate to just run away. I was so miserable that I started to take solace in books and writing. I wrote a novel my freshman year in Earth Science class about teen assassins and got a D in the class. My mother will never let me forget it. I also had an age-inappropriate relationship that I hid from my family. My mother learned about ADHD from a co-worker and fought the school to have me tested and get the proper IEP. My grades did a 180. And even though I made it out alive and got into college, I said I would never step foot in a high school again.

Fast forward many years later, I was on a walk with Laurie Halse Anderson, right before my second book, Monday’s Not Coming, was set to release. I told her I didn’t know what I should do next in my career or what I should write about. She said, “You need to start doing school visits, so you can remember who you’re writing for.”

Since that day, all I do is go to high school and talk to kids. I have met dozens of kids who’ve read my books, and saw themselves in it. I’ve had girls tell me they need help getting out of relationships like in Grown. Talked to teachers who had students missing like in Monday. Even talked to kids who wanted to be like Malcom X. Creating books that kids needed, that I needed when I was their age, is one of my greatest joys.

Dedication in Let Me Hear a Rhyme: For the hustler in front of my auntie's building, who taught me how to move in a room full of vultures. For Brooklyn, home no matter where I go.

There was this drug dealer that used to love hanging out in front of my aunt’s building in East New York. He would buy all the kids in the neighborhood ice cream and candy, but I couldn’t stand him. I knew what he was selling and I saw what crack did to my family members. So I wouldn’t talk to him. I refused his treats. And he was determined to make me smile, going out of his way to try to make me smile or talk to him. And when I would ignore him, he’d laugh. He once said, “That’s okay baby girl. You stay quiet. Real hustlers don’t make noise.”

That was a life lesson I took seriously. See, I recognized that no one understood my dream. That being a writer was risky. So, I worked on my books in silence. I spend countless weekends alone in my apartment, revising and revising, sending out countless query letters. In that time, there was a lot of rejection. A lot of no’s. I had an agent who said she wanted to rep me but then would take random vacations for months with radio silence. There was an agent who specifically said, “Black people don’t read thrillers.” After maybe two years of rejections, I told my mentor Tayari Jones I was ready to give up. She asked me about my book and I told her what it was about and she said, “It sounds like it’s a YA.” I said, 'What’s that?' I saved my pennies to hire an editor to help me clean up the book. I wasn’t giving up, I was just gonna pivot.

That was a life lesson I took seriously. See, I recognized that no one understood my dream. That being a writer was risky. So, I worked on my books in silence. I spend countless weekends alone in my apartment, revising and revising, sending out countless query letters. In that time, there was a lot of rejection. A lot of no’s. I had an agent who said she wanted to rep me but then would take random vacations for months with radio silence. There was an agent who specifically said, “Black people don’t read thrillers.” After maybe two years of rejections, I told my mentor Tayari Jones I was ready to give up. She asked me about my book and I told her what it was about and she said, “It sounds like it’s a YA.” I said, 'What’s that?' I saved my pennies to hire an editor to help me clean up the book. I wasn’t giving up, I was just gonna pivot.

There was an agent who wanted to change the ending of Allegedly. And when I refused, they passed. If had listened to that agent, I don’t think I would be here today. I eventually signed with my first agent, Natalie Lakosil, was a junior agent at the time and took a chance on me.

The entire time, no one knew what I was doing. I remained quiet, worked on my dreams in silence. I didn’t tell people anything until I signed my first book deal. And even when my book launched, there wasn’t a lot of buzz around it, no big marketing campaign. I remained quiet, determined, and kept writing. And slowly, there was a growing chatter. Allegedly was being talked about in Facebook groups and book clubs. Word of mouth saved my career more than any splashy headline. So I look back and I am so grateful for those rejections. I continually say that rejection is nothing but redirection in the right direction. And that redirection rescued me. Rescued my book, my career, and my dream. I learned that noise doesn't get you where you want to go, the work does. You have to have a good book. I take every book I write seriously.

In Storm: Dawn of a Goddess, the dedication reads: For my first star, may you always shine bright.

Roe vs. Wade was overturned in June of 2022, and states started passing abortion laws, but things were very fuzzy and unclear. Six months later, in January of 2023, I suffered a miscarriage, for my first ever pregnancy.

I was living in Atlanta, and because of these unclear abortion restrictions that had been put in place, the doctors in Georgia, attempting to play it safe not be thrown in jail, basically said in so many words that they are not allowed to do anything for me, and that I should go home and take some aspirin.

So, I did go home, back to New York, where I received proper treatment, treatments that I had never heard of before. It was a surreal feeling going from hearing a heartbeat one week, to none the next, to giving key note two days later in front of a room full of kids, to then receiving an edit letter for a book that was way overdue.

While I was in my hospital room, I remember staring at the ceiling in the middle of the night, feeling so stupid. I was 41 and had no clue that miscarriages fell under the jurisdiction of abortion rights. Why didn’t I know this? Where would I have learned this? It wasn't in any health education class I ever took. It wasn't in any book I ever read, and I've hundreds. It's the same feeling I got when I researched about girls in group homes, in prisons, or missing teens, or this history behind houses being stolen to further gentrification. WHY DON'T I KNOW THIS? WHY DON’T MORE PEOPLE KNOW THIS?

In Georgia, two Black women, Amber Thurman and Candi Miller, died due to abortion restrictions. More recently, there was the case of Adriana Smith, who was kept on life support while brain-dead to ensure her pregnancy could continue. Every time I see mentions of a Black woman dying due to maternal health, I think, by the grace of God go I, that could’ve been me. But then I also think, I’m not ready to die yet. I still have so many more books living under my skin.

A few months after my miscarriage, I was pregnant with my now seventeen-month-old daughter, but every day, I worked on my stories like they were my last, because you just never know. That’s why I can never truly explain how this award came right on time, when I was questioning myself and my worth, and my place in this industry. To know if something had happened, that I really did leave a mark, really means everything to me. I cannot thank you all enough.

I considered writing a book about the experience and then stopped myself, saying ehhh, abortion is such a rough topic, I don’t think kids have to learn about this, and I don’t want to be the one to teach them. And then I laughed. Isn’t that just like an adult, not wanting kids to learn about hard things because it makes them uncomfortable? It made me look at the book banners in a different light. And don’t get me wrong, I still can’t stand those fools. But it made me remember the very human part of fear and insecurities, and how we’re all very much still teenagers in ageing bodies.

I tell this story not ‘cause I want to share my trauma, just like I don’t write about hard topics to traumatize kids. The stories I tell are intentionally geared toward building knowledge, empathy, and compassion. Unforgettable books create core memories that remind each other of our humanity, in the hope that we ultimately become a better society that leads with love

This new generation of kids deserves a new generation of authors. Authors who are bold, unapologetic, pushing boundaries and respecting their realities. Authors who will prepare them with care. Not because we want to be provocative or force kids to grow up too quickly, but because we know the damage ignorance and callousness have done. We are witnessing it every day. But kids don’t just need books, they need forward-thinking adults as well. It takes a village to raise child. It takes love, patience, respect, and kindness to raise an emotionally intelligent adult.

And I want to end this with my favorite dedication. It’s in The Weight of Blood: This one is for me! For the little girl in pigtails who went running for the TV whenever her favorite horror movie came on, doing the absolute unimaginable when so many doubted her dreams, including herself. Look at you now, Tiff-Tot. Look at you now.

Some writers are born and some writers are created. I'll always be a writer. There is no retiring from what you were born to do. Honor of a lifetime. And this award has truly validated my career.

As I said, I think dedications are beautiful and important, so I dedicate this amazing honor to libraries. Brooklyn Public Library, where I got my first library card, Brooklyn Public Library Macon branch that helped me research Let Me Hear a Rhyme. Grand Army Plaza branch, that housed me during Hurricane Sandy aftermath, where I wrote Allegedly. To Hendrick Hudson Free Library in Montrose, NY. Anacostia Library in Southeast DC. To the Libby app who entertained me during COVID. To Founders Library and Undergrad Library (aka Club UGL) at Howard U. To Northeast Branch Library in Atlanta who graciously entertains my daughter with storytimes. Indianapolis Public Library Center for Black Literature and Culture, Cleveland Public Library. Thank you for all that you do. Thank you. Thank you.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!