Using Personal Learning Communities To Improve Nonfiction Collections

A program that brings school librarians together over Zoom to share ideas and support one another has helped collection development.

|

|

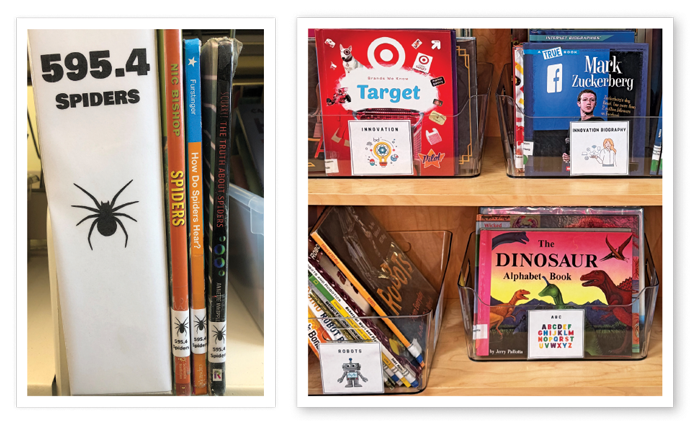

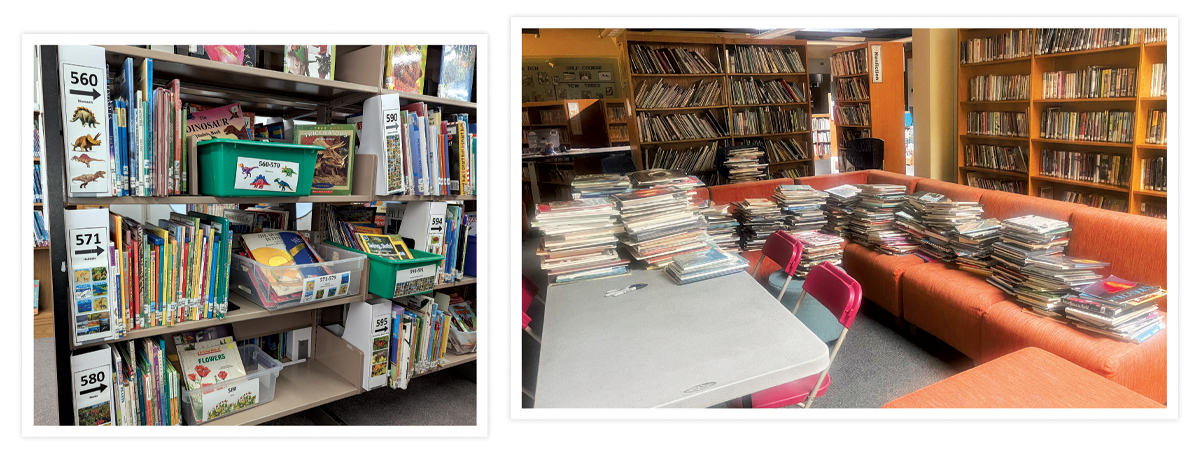

From Left: Using bins to spotlight subjects; Zoan Barefield aggressively weeded her outdated collection.Photo from left: Marti Smallidge; Zoan Barefield |

While teachers are surrounded by colleagues who can share ideas and offer advice, many school librarians are often on their own. Every. Single. Day.

What’s the solution? A Personal Learning Community (PLC). Imagine monthly online meetings with a group of librarians working with the same grade levels to discuss a specific topic, such as revitalizing a nonfiction collection. It’s a chance to learn and grow, build camaraderie, and commiserate.

In early 2022, library and literacy researchers Mary Ann Cappiello, Xenia Hadjioannou, and Pam Harland had this vision and brought it to life for a group of 11 New Hampshire elementary school librarians.

During the 2022–23 school year, Cappiello, Hadjioannou, and Harland hosted a monthly PLC Zoom with the goal of increasing awareness of and access to nonfiction books. Participants discussed ways to make small, manageable changes to their collections and instruction, then put the ideas into action. The librarians got so much out of the experience they asked to extend the PLC into the next school year.

“By the end of the year, the librarians were seeing a clear increase in student interest in nonfiction, and teachers were more engaged with nonfiction texts as well,” says Harland. “Just as powerful was the collaborative environment. The PLC created a space where everyone could reflect, take risks, and grow together. One participant said she loved getting out of her ‘library cave’ to talk through ideas with other librarians.”

After hearing about the project, I asked Cappiello, Hadjioannou, and Harland if I could run a Nonfiction PLC in my home state of Massachusetts. With their approval, I teamed with school librarian Laura Beals D’Elia, hosting 17 participants from January through December 2024.

During the first few meetings, the librarians learned about and discussed possible projects related to collection development and/or instruction. They then conceptualized, planned, and implemented a nonfiction-focused project in their library. While the projects were underway, participants reported their progress to the group, offered suggestions and support, and celebrated successes.

Participants share openly with each other, as a key element to the group is discretion regarding the conversations—this is a space to speak without fear of judgment or comments or discussions being shared outside of the group.

Here are the nonfiction collection curation projects completed by the Massachusetts librarians:

|

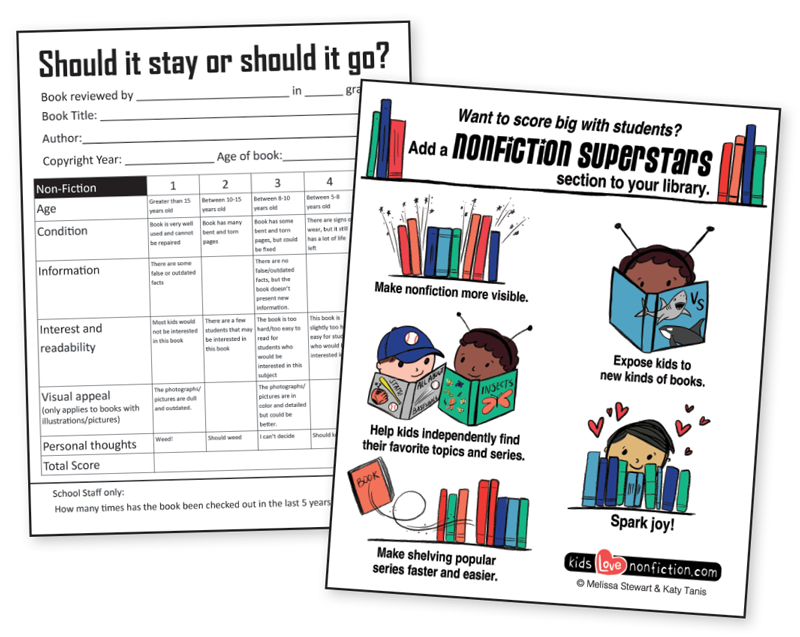

A weeding worksheet and tips for sparking more interest in nonfiction.From left: Zoan Barefield; Melissa Stewart and Katy Tanis |

Weeding

Most school librarians weed their collections a little at a time, but when Zoan Barefield arrived at her K–8 school, the library had more than 37,000 books, or 200-plus titles per student. Many of the books were outdated, falling apart, or moldy. Barefield discussed this massive weeding project on the monthly calls and shared her idea to enlist the help a local Eagle Scout looking for a community service project. She then reported back to her peers on the progress and success.

Over a three-day period in June 2024, a small group of scouts pulled books off the shelves, looked at the copyright date of each book, and made piles of books published before 2009. Barefield evaluated each book. The scouts weeded about 60 percent of the nonfiction section, repaired damaged books, and packed up 70 boxes of books that would be removed from the collection.

“The scouts did a great job,” says Barefield. “They really jump-started the weeding process, but the project is ongoing.”

At the end of the 2024–25 school year, the collection had approximately 22,000 books, or 120 titles per student. Students in grades 5–8 continue to weed using Barefield’s “Should It Stay or Should It Go?” worksheet.

Filling gaps

D’Elia, a K–3 school librarian, has been at her current school for nine years, and her curation project was addressing gaps in her nonfiction collection. She noticed that she didn’t have enough dinosaur books, many of her books about health and the human body were outdated, and her selection of books about countries was “miserable.” She went in search of a solution.

As D’Elia looked for books to fill the holes, she found a great series through one of her vendors, only to discover that the vendor did not have the entire series. She wanted the series, and she wanted to buy all of the books at once, then not worry about that section for a while.

Eventually, D’Elia decided to contact publishers directly.

“This has been a gamechanger,” she says. “Publishers can send in a series. They also offer promotions and discounts and process the books for free.”

Instead of buying a few books across a broad range of topics, D’Elia now focuses on just a few topics each year and buys everything she needs.

“Each year, I choose new topics and a new publisher,” she says.

D’Elia says this practice better serves her students.

“You know when a reader shows you the back of a book with all the other books in the series and they point to one of them and ask, ‘Do you have this one?’ That used to stress me out because I typically didn’t. Now I confidently say, ‘Yes!’”

|

From left: Changing Dewey to help students find titles; Books that are displayed face out get more attention from students.Photo from left: Rachel Small; Wendy Garland |

Ditching Dewey

Some of the PLC librarians spent their time tweaking the Dewey Decimal System to suit the needs of their school community. Elementary school librarian Wendy Garland and K–12 librarian Becky Sniffen moved farm animals and pets into the 500s with the other animal books. Sniffen also moved biographies of athletes into the sports section.

“These changes have really bumped up their circulation,” says Sniffen.

K–5 school librarian Liza Halley has also made changes to her biography section. She’s arranged books by subcategories, including Artists, Athletes, Change Makers, STEM, U.S. History, and World Leaders.

“This new organization helps with wayfinding for students and also with library lessons that support the EL curriculum our school utilizes,” says Halley. “It also avoids siloing biography subjects based on their race or gender identity.”

In the 900s, Halley thought about categories students are most drawn to and made separate numbers for all the president and American Revolution books.

Highlighting popular series

Many school librarians spend a lot of time helping students locate books in their favorite nonfiction series because the titles are shelved all over the library. To solve this problem, sections that consolidate popular nonfiction titles are increasingly common. They’re the perfect spot to shelve series like “Who Would Win?,” “Fly Guy Presents,” and “Weird But True,” as well as a range of books on topics like sports, the military, gaming, and unexplained mysteries.

“Students can find the books they want with little or no assistance,” says D’Elia, “and it simplifies reshelving frequently checked-out books.”

These special sections go by many names, such as Popular Nonfiction and Nonfiction Superstars. D’Elia chose the name “Nonfiction Stars” and added a star-shaped sticker to each book’s spine. Since she didn’t change the books’ call numbers, the stickers let volunteers know where to shelve the books. As an added bonus, D’Elia loves that when a student asks where to find a book they didn’t know was in this section, she gets to say, “Go look under the stars.”

The benefits of bins

The use of bins was a popular topic of conversation in the group and project for the participants.

“It’s so much easier to rearrange a section once it’s in bins,” says K–5 teacher librarian Rachel Small. “Plus students can easily slide the bins off the shelves to look at the books more carefully.”

Small labelled her clear bins with words and a picture on the end lengthwise as well as widthwise, so they can be oriented either way on a shelf. She places them lengthwise if space is tight in a section or widthwise so books face out.

“The books that are face out get checked out much more quickly,” Small says.

To make finding books even easier, Small created a second copy of each bin label and stuck it to the end of the corresponding bookcase. This helps students know what topics are shelved on a particular bookcase with a quick glance.

K–1 school librarian Marti Smallidge agrees that forward-facing bins with clear labels have been “transformative” for her students.

“Flipping through books that are facing you is much less daunting than traditional shelving, especially for students who cannot yet read spines,” she says.

Smallidge notes that her labels are almost completely pictorial, “which is perfect for our pre- and early readers. Students walk among the shelves and discover sections they didn’t know existed. They can also find exactly what they’re looking for without adult assistance.

According to Smallidge, this change has affected how her staff spends their time.

“Now we can focus on students with questions that are more nuanced than ‘Where are the dinosaur books?’” she says.

Garland developed a shelving system that mixes bins with small topic-focused sections marked with white magazine holders that are labelled with a call number, a one-word description, and a picture. She also created a matching pictorial spine label for each book.

“Now, putting a book away is as easy as matching the spine label to the bin,” says Garland.

“And finding a book is as easy as pointing a student to the correct aisle and telling them to look for a bin with that particular topic’s picture. Creating a visual guide increased accessibility and independence in our library.”

This school year, a Nonfiction PLC will launch in Kansas, hosted by the Kansas Association of School Librarians, building on the successes of the program in New Hampshire and Massachusetts.

“It really helped me grow as a librarian,” says Sniffen. “It’s particularly exciting now when I can connect a ‘nonreader’ with a nonfiction book that really piques their interest!”

Melissa Stewart is a children’s literature researcher and author of more than 200 science books for children.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!