Christopher Paul Curtis: "Keep Fighting" | The Newbery at 100

Christopher Paul Curtis reflects on his post-Newbery life, censorship attempts, and why his books, centering of African American history, are necessary, especially today.

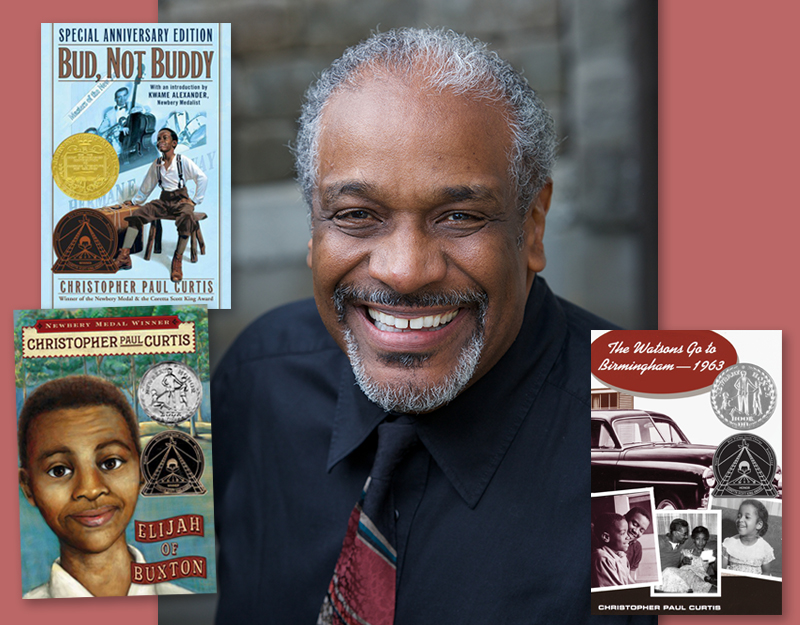

Christopher Paul Curtis has been recognized by the Newbery committee three times. He was the recipient of a Newbery Honor in 1996 forThe Watsons Go to Birmingham—1963 (Delecorte), and in 2008 for Elijah of Buxton (Scholastic). He received the Newbery Medal in 2000 for Bud, Not Buddy (Delacorte).

Curtis’s award-winning fiction featuring African American families and children provides insight into the importance of history and its relationship to the present. In this interview, Curtis reflects on his post-Newbery life and offers insight into why his books, and their centering of African American history, are necessary, especially today.

What were some ways your life changed (if it did) after you won the Newbery Medal and the Newbery Honor? Did winning enable you to do things that you wouldn’t have been able to do otherwise?

I don’t know if other authors do this, but I approach life in much the same way I approach writing a novel. I’ll come up with a scene or a scenario and start to imagine possible outcomes. When writing, I ask myself, “What would happen if this character did X?” Then I play through the consequences of that action.

I do the same thing with life events. In 1996, when The Watsons Go to Birmingham—1963 won a Newbery Honor, I played this game and went through all of the possibilities this momentous event could trigger.

I went from the lows (I’d be tooling around Flint, MI, stopping strangers on the street to say, “Psst, I wrote a book. I’ve got some copies in the trunk. Wanna buy one?”) to the highs (“I’m gonna have to brush up on my Swedish and rent a tux for the Nobel Prize for Literature ceremony”). The hope, of course, being that reality would end up closer to the Scandinavian end of the scale.

And it was!

I was 42 years old and suddenly began traveling. I’d never been west of Chicago or south of Columbus or north of Saginaw, and I was now going all over the country. And when I looked up my name in the card catalog, there it was next to another Christopher Curtis, who wrote a book called How to Be Your Own Chimney Sweep!

When my next book, Bud Not Buddy, won the Newbery Medal, the changes were even greater. For the first time in my life, I wasn’t living paycheck to paycheck and would shamelessly answer the phone not fearing bill collectors.

I was able to quit my “real” job and become a full-time writer!

What advice do you have for educators and families who might be facing challenges for teaching The Watsons Go to Birmingham—1963 or any of your books?

I feel as though I’m preaching to the choir, because I bet anyone who is reading this interview in School Library Journal is already well aware of the dire situation we’re in. All I can say is keep fighting, be just as vigilant and assertive as the people who seem bound and determined to drag the whole country back into the 1950s. Oppose them at every opportunity. These are particularly scary times, and these are particularly scary people, but we can’t allow ourselves to be bullied or intimidated. I believe it’s a good sign when a book makes certain people uncomfortable.

Why do children need to read your books, especially now?

My loftiest ambition as a writer is to be a catalyst to get young people to feel even a tenth of what I feel when I’m reading a book that touches me. The fact that a reader is contributing to the story from their perspective makes a book personal and can light a flame in that person. I want to light that fire in someone.

When I’m speaking to a group of students and see the occasional examples of yawns and restlessness, I tell myself, that’s okay, you might not be reaching that person, but if there’s one student in the whole auditorium who my words reach, then my job is done. I feel the same way about my writing. All I need is that one [person].

You have pushed forward African American historical fiction for children quite powerfully. What opportunities do you still see for the genre? What still needs to be addressed? What hopes do you have for the genre?

Thank you! Historical fiction is indeed a powerful way to entice readers into worlds they probably otherwise wouldn’t examine or know about. By placing a relatable character in an historical context, my goal is to have readers, young or not, come along for the ride. If done properly, this leads them to empathize with the characters, and a connection is formed. And these connections can open minds and expand points of view. Historical fiction serves as a perfect framework for telling countless stories.

Are there any books you think all children and young adults should be required to read?

At the top of my list would be Monster by Walter Dean Myers. Not only is this masterpiece a great read, but it is also a tool for those trying to understand how to write a great book. In an unconventional format, Myers builds suspense, asks relevant questions, and proves how deceptively simple language can grab hold of a reader.

Is there anyone currently writing for children and young adults, especially Black children and young adults, who excites you? If so, who are they, and why?

There are, of course, far too many writers doing beautiful work to name even a fraction of them. My advice would be to talk to a librarian—they are experts on this subject, and compared to theirs, my suggestions would not be so well-informed.

So as not to completely dodge the question, though, a few authors I have been enjoying lately are Sundee T. Frazier, Nic Stone, two Jerrys (Mr. Craft and Mr. Spinelli), Varian Johnson, and Laurie Halse Anderson. And, yes, I realize not all of them are African American, but cross-cultural reading is important for all children. After all is said and done, good writing is good writing.

Dr. Kimberly N. Parker is the Director of Crimson Summer Academy at Harvard University (MA)

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!