Q&A with Maria Russo and Emily Jenkins: Grown-Ups in Picture Books and The Kitten Story: A Mostly True Tale

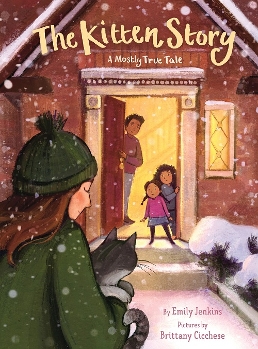

When a cat-loving family decides to bring home a pet, their quest reveals the highs and lows of everyday family life in this heartwarming story—perfect for kitten lovers and everyone who’s ever longed for a pet.

MARIA RUSSO: Hello, Emily!

MARIA RUSSO: Hello, Emily!

EMILY JENKINS: Hello! Readers might not know this, but Maria and I go way back. We attended grad school together; then she hired me to write reviews when she was a book editor at Salon. We had babies at the same time and went to mommy-baby yoga and the park; I wrote reviews for the New York Times when Maria was the Children’s Books Editor—and now she’s my picture book editor!

MR: All true! And The Kitten Story made my heart sing when I first read it. Of course, the characters are based on your family, and on your cat, all of whom I know and love. Then the adorable illustrations came in from Brittany Cicchese, who is such a talented artist, and happens to be a librarian!

MR: All true! And The Kitten Story made my heart sing when I first read it. Of course, the characters are based on your family, and on your cat, all of whom I know and love. Then the adorable illustrations came in from Brittany Cicchese, who is such a talented artist, and happens to be a librarian!

It’s a feel-good pet rescue story…but also so much more.

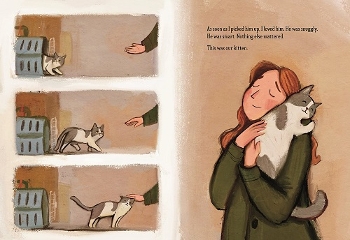

EJ: The true subject of The Kitten Story is family negotiations. What do you do when you disagree? Do you take a poll? Argue it out? Does one parent have final say? When my family adopted Blizzard, I felt I could bring something fresh to the “getting a pet” genre by writing about the ways we worked out our disagreements.

MR: Let’s also talk about how you broke a rule for picture book writing, my rascally friend. And got away with it, beautifully.

EJ: The rule is: your protagonist must be a child. Or a bunny.

MR: That’s what a lot of picture book experts insist! They say kids must be at the center of a story and that grownups are boring. But here you made Mommy the narrator.

EJ: Well, some adults are boring. And one of the key jobs of picture books is to center and validate the emotional lives of children.

EJ: Well, some adults are boring. And one of the key jobs of picture books is to center and validate the emotional lives of children.

However, there’s a long history of adult protagonists in books for the very young. Sure, fairy tales like “Rumpelstiltskin” have adult heroes, but also older picture books like The Man Who Didn’t Wash His Dishes (Phyllis Krasilovsky, illus. Barbara Cooney) or Caps for Sale (Esphyr Slobodkina).

Then there are picture books—old and new—centering young animal heroes who live independently and cook their own food. These characters occupy a liminal space between child and adult. In Peter Brown’s Mr. Tiger Goes Wild, for example, Mr. Tiger is an adult with the feelings of a three-year-old—he wants to take off all his clothes and streak through the town center. Christopher Denise’s Knight Owl goes to knight school and gets a job but is somehow still a baby owl. In Hsu-Kung Liu’s The Orange Horse, a horse searching for his lost brother travels through a city on his own, showing a photograph to everyone he meets—but he’s still a little boy. Or think Arnold Lobel’s Frog and Toad living on their own but yelling at plants that don’t grow fast enough.

Back to adult humans: they’re less common in today’s picture books, but some wonderful recent examples include David Small’s Fenwick’s Suit, Officer Buckle and Gloria by Peggy Rathmann, and lots of books by Jon Agee—Milo’s Hat Trick, Terrific, etc.

MR: Those are all such great books. But in most of them, the adult functions as kind of an outsider, or childlike in some way. Or there are  kids in the story, but the adults are a bit dim or are really there to help the children. This isn’t how we experience your book. Mommy is fully the responsible adult, with her own opinions.

kids in the story, but the adults are a bit dim or are really there to help the children. This isn’t how we experience your book. Mommy is fully the responsible adult, with her own opinions.

EJ: Yes, it’s first-person mom! I tried writing it from a kid’s perspective, but it wasn’t as meaningful (in terms of my theme of family negotiations) and more importantly, it wasn’t as funny. I treated the project just like I was telling a car full of children the story of what happened in my actual family, in the most amusing way I knew how.

MR: Don’t forget Tulip and Rosie. They’re child characters with strong opinions and do manage to drive the action—as much as children in any family can.

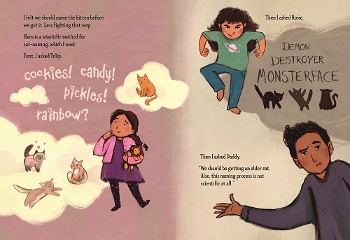

EJ: For sure. Rosie is the older sister—ready to brave danger to get a kitten, and eager to name the new pet after some kind of terrible monster. Tulip is the cat-obsessed younger sister, making signs to welcome the kitten home and wanting to name it after some kind of dessert. They don’t always get along perfectly—but I knew from experience that even when families disagree, there can still be a happy ending.

MR: And the happy ending in The Kitten Story is also a really happy beginning—a new pet. Not much is better than that!

SPONSORED BY

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!