Powerhouse YA Authors on World-Building and Agency | SLJ Day of Dialog 2017

Attendees at SLJ’s ninth annual Day of Dialog on May 31 in New York City were treated to a lunch keynote from the acclaimed Megan Whalen Turner and a panel of blockbuster YA authors.

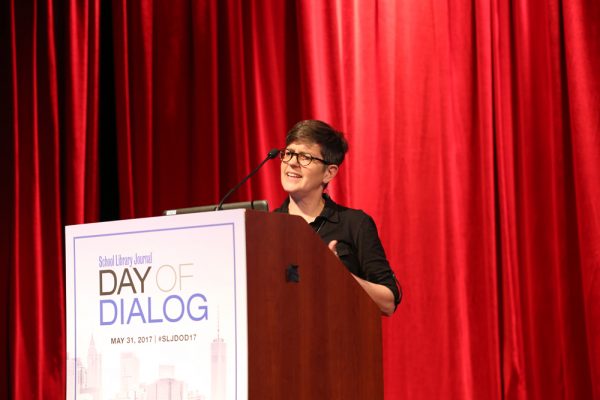

SLJ Day of Dialog 2017 Luncheon speaker Megan Whalen Turner. Photo ©Julian Hibbard for SLJ.

Young adult literature had a strong showing at SLJ’s ninth annual Day of Dialog on May 31 in New York City. Attendees were treated to a lunch keynote from the acclaimed Megan Whalen Turner and a panel of blockbuster YA authors. Instead of focusing on what inspired her to return to her acclaimed “The Queen’s Thief” series (HarperCollins), Turner’s talk focused on a design-centric topic—maps. When she first began the series over 20 years ago, the author knew that she wanted to write a fantasy set anywhere but Middle Earth. On a trip to Greece, she found her setting. Though her editor suggested adding maps to her books to supplement the story, Turner felt that would give them the “Middle Earth” tone that she was trying to avoid. Turner’s aversion to maps has long been noted among her fans. Since the publication of the Newbery Honor–winning series opener The Thief (1996), readers have repeatedly requested a visual representation of the rich, complex Attolia and its environs. One reason she insisted against it was that she felt it was “important to leave certain things up to the reader.” The author informed the captivated audience that she finally succumbed to requests of her editors and fans in the latest volume in the series, Thick as Thieves (May, 2017). Showing a series of maps, she described the detailed process that she undertook, along with cartographers, designers, editors, and academics, to get them just right. Inspired by thousands of maps that she encountered in her research at the Vatican, Turner understood that, “Every map has a narrative, perspective, and a worldview that it’s pushing.” The author, who is known for her character-driven books, connected her desire for a nuanced map to the complex storytelling that is typical her work. “I really wanted to make it possible for my readers to get a sense that [in books], there’s [often] an individual narrator who has a viewpoint that is not entirely reliable.” “What you see depends on what viewpoint you're looking from," she said in closing, a statement that resonated during the YA literature panel that followed.Imagination on Steroids: Powerhouse YA Fiction

YA Panel at SLJ's 2017 Day of Dialog, from left to right: Nnedi Okorafor, M.T. Anderson, Maggie Stiefvater, Greg Katsoulis, and Mitali Perkins.

Moderated by Monica Edinger, an educator at The Dalton School in New York City, the panel on “Imagination on Steroids” featured M.T. Anderson, Gregory Scott Katsoulis, Nnedi Okorafor, Mitali Perkins, and Maggie Stiefvater. Each spoke about the inspiration behind their most recent works of fiction. In the “Akata Witch” series, Okorafor hopes to create the “African Harry Potter,” she said. Akata Witch (2011) and its sequel Akata Warrior (Nov. 2017; both Viking) take place in present-day Nigeria. The protagonist, American-born Sunny, has recently moved there with her family and has discovered that she’s part of a secret magical society—a real society that exists in Nigeria that Okorafor altered somewhat for the book. “I am very attracted to certain cultural elements—whatever was forbidden and secretive, my ear was attracted to that. I’ve gathered those stories and beliefs,” in these books, Okorafor said.

Moderator Monica Edinger and Nnedi Okorafor.

Anderson’s latest hearkens back to his groundbreaking Feed (2002); it also takes place in a futuristic world. Earth has been taken over by aliens in Landscape with Invisible Hand (Candlewick, Sept. 2017). The main character is a landscape artist who is trying to grapple with this colonization. The story idea came out of his research for his recent nonfiction work on the Soviet Union, he said. While writing this slim novel, Anderson asked himself, “What if the earth itself was a ‘developing country’ in someone else’s empire? How do you define yourself after you have been defined by another for so long?” Stiefvater's All the Crooked Saints (Scholastic, Oct. 2017) also arose from a series of questions from teens and readers who reached out to her via social media with requests for advice. “What does it mean to give advice when you’re someone who needs advice yourself?” she quipped. Set in southern Colorado during the 1960s, the novel follows a family who can perform a strange miracle: They can vanquish the inner darkness of those who come to them by making it visible. But there’s a catch. The family member’s own inner darkness is unleashed in the process. In the universe of Katsoulis’s All Rights Reserved (Harlequin Teen, Aug. 2017), all language is copyrighted and every bit of communication gets charged to one’s account. The debut author was inspired to write this dystopian work when he learned that William Faulkner was sued for using the word Coke in one of his books, along with the fact that oppressive copyright trolling has become more aggressive over time. Katsoulis wanted to explore: What would cause a society to copyright words? While Katsoulis’s novel is about the power of words, Perkins’s latest book addresses the power of memory. Her mostly autobiographical tale is based on her family’s immigration to New York City from Bangladesh. Chronicling the travails of sisters acclimating to a new country,You Bring the Distant Near (Farrar, Sept. 2017) was inspired by the words of Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore: “'You've made a stranger a friend'—that's what this book is about," Perkins recited with emotion. She went on to credit her parents’ 62-year marriage as a touchstone for the novel. In creating what Perkins calls “Joy Luck Club meets Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants with an American Bengali family,” she didn’t shy away from touching upon tough topics, such as “shadism,” or the practice of elevating lighter skin, and caste systems, or what her mother called “all of our family quarrels.” However, she also wanted to include the beautiful aspects of immigration and family. Perkins hoped to explore “the best that American can be. When America is at its finest, it brings people together who wouldn’t ordinarily be.” For All the Crooked Saints, Stiefvater wanted to fashion a setting where strange and wonderful things could happen—even Bob Dylan appearing in your kitchen and demons dancing on the lawn. “I’m creating a world where all of this is possible,” she said, “one in which you could drive to and suddenly be lost in.” Okorafor’s world-building also includes strange happenings. The fantasy author often takes strange things that already exist and amps them up for the sake of the storytelling and sense of place. “A lot of things you don’t have to amp up,” she said. “‘The People Who Could Fly’ tale comes from the Igbo people, from which both my parents are descended. I have relatives who tell me, ‘I see people flying all of the time.’ I didn’t have to build the world for this series. It was already there.” Family is also an important part of Okorafor’s books. Her protagonist belongs to a secret society she can’t tell her family about—a big conflict for the main character, who is very close to her parents and siblings. Sunny must find ways to have her adventures with her family still very much a part of her life. “Parents get killed off usually, and I understand why writers to do that,” she said. “That conflict was harder to write, but more realistic and more dynamic” for her books. The teens in Anderson’s Landscape have unusual relationships with their families. His main character is expected to provide for the family. “[That’s] the way it is in many other places,” Anderson said. “In most homes in the United States, teens are consuming like adults, but they don’t feel like they have to contribute like adults. There’s no one else like that in your house, or you would otherwise evict them,” he joked.

While Katsoulis’s novel is about the power of words, Perkins’s latest book addresses the power of memory. Her mostly autobiographical tale is based on her family’s immigration to New York City from Bangladesh. Chronicling the travails of sisters acclimating to a new country,You Bring the Distant Near (Farrar, Sept. 2017) was inspired by the words of Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore: “'You've made a stranger a friend'—that's what this book is about," Perkins recited with emotion. She went on to credit her parents’ 62-year marriage as a touchstone for the novel. In creating what Perkins calls “Joy Luck Club meets Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants with an American Bengali family,” she didn’t shy away from touching upon tough topics, such as “shadism,” or the practice of elevating lighter skin, and caste systems, or what her mother called “all of our family quarrels.” However, she also wanted to include the beautiful aspects of immigration and family. Perkins hoped to explore “the best that American can be. When America is at its finest, it brings people together who wouldn’t ordinarily be.” For All the Crooked Saints, Stiefvater wanted to fashion a setting where strange and wonderful things could happen—even Bob Dylan appearing in your kitchen and demons dancing on the lawn. “I’m creating a world where all of this is possible,” she said, “one in which you could drive to and suddenly be lost in.” Okorafor’s world-building also includes strange happenings. The fantasy author often takes strange things that already exist and amps them up for the sake of the storytelling and sense of place. “A lot of things you don’t have to amp up,” she said. “‘The People Who Could Fly’ tale comes from the Igbo people, from which both my parents are descended. I have relatives who tell me, ‘I see people flying all of the time.’ I didn’t have to build the world for this series. It was already there.” Family is also an important part of Okorafor’s books. Her protagonist belongs to a secret society she can’t tell her family about—a big conflict for the main character, who is very close to her parents and siblings. Sunny must find ways to have her adventures with her family still very much a part of her life. “Parents get killed off usually, and I understand why writers to do that,” she said. “That conflict was harder to write, but more realistic and more dynamic” for her books. The teens in Anderson’s Landscape have unusual relationships with their families. His main character is expected to provide for the family. “[That’s] the way it is in many other places,” Anderson said. “In most homes in the United States, teens are consuming like adults, but they don’t feel like they have to contribute like adults. There’s no one else like that in your house, or you would otherwise evict them,” he joked.  Stiefvater’s book also touches upon a family dynamic not often seen in YA lit: the grown-ups are as integral to the plot as the teen characters. “I wanted the adults to change alongside them, like in [the films] Amelie, Chocolat, and Big Fish. It takes a village,” she said. The adult characters don’t play a big role in Katsoulis’s book— the teens drive the plot. Protagonist Speth finds most of her agency in not speaking. And with that powerful act, she starts a revolution. That touches on something that Anderson loves about writing for teens—the fact that young people have more idealism and a desire to do something about the wrongs of the world. “[As adults] we get worn down,” he said. “When you’re confronted by the illogicality and horror of the world, the appropriate response should be continuing outrage. But teens don’t have those extra years of defeat [yet]. I love my memory of my idealism as a teen; it felt fierce and inexhaustible.” Okorafor’s desire to write about adventurous teen female protagonists in patriarchal society also speaks to agency and power. “In Nigeria, the girls were always doing something: chores, work, cooking,” she said. “I want to write the kind of story that would be so good that these girls would want to hide away and read instead of doing their chores.”

Stiefvater’s book also touches upon a family dynamic not often seen in YA lit: the grown-ups are as integral to the plot as the teen characters. “I wanted the adults to change alongside them, like in [the films] Amelie, Chocolat, and Big Fish. It takes a village,” she said. The adult characters don’t play a big role in Katsoulis’s book— the teens drive the plot. Protagonist Speth finds most of her agency in not speaking. And with that powerful act, she starts a revolution. That touches on something that Anderson loves about writing for teens—the fact that young people have more idealism and a desire to do something about the wrongs of the world. “[As adults] we get worn down,” he said. “When you’re confronted by the illogicality and horror of the world, the appropriate response should be continuing outrage. But teens don’t have those extra years of defeat [yet]. I love my memory of my idealism as a teen; it felt fierce and inexhaustible.” Okorafor’s desire to write about adventurous teen female protagonists in patriarchal society also speaks to agency and power. “In Nigeria, the girls were always doing something: chores, work, cooking,” she said. “I want to write the kind of story that would be so good that these girls would want to hide away and read instead of doing their chores.” RELATED

RECOMMENDED

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!