2018 School Spending Survey Report

Tomi Ungerer: The Comeback Kid

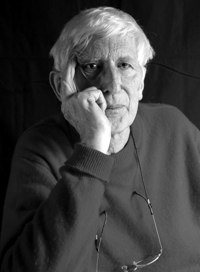

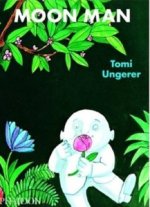

Tomi Ungerer, best known for his children's books—and his erotic and political illustrations—is back in the United States after a nearly 15 year absence. The French illustrator has a few good reasons to return: Phaidon is republishing eight of his books and the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art in Massachusetts is celebrating his upcoming 80th birthday with a retrospective exhibition of his works, which opens on June 18. That's not bad, considering that his political views and racy drawings so alarmed publishers that years ago they let his catalog go out of print. SLJ sat down with Ungerer, the author and illustrator of the bestselling classics Moon Man and The Three Robbers, to talk about why he's often the target of controversy, his love of libraries, and how it feels to visit the Big Apple again after all these years. What's it like being on U.S. soil again? I feel like the Moon Man coming back to Earth for the second time. I was apprehensive after so many years coming back to New York City, but I realize that apart from a few skyscrapers, which by the way I loathe, it hasn't changed. Does New York hold a special place in your heart? I love the spirit of New York. I have been asking myself, why are some towns dynamic? I realize that one feels liberated when one comes to New York City, and anything is possible. I arrived here with $60 in my pocket at the age of 25, and within a year I had my first book, The Mellops Go Flying (Harper & Row, 1957), published. A few years later, I bought my first brownstone on Commerce Street. It was the only house in New York City that was painted pink, and it was Aaron Burr's house, the bad man of American politics. This trip has another purpose because I am writing about my New Yo

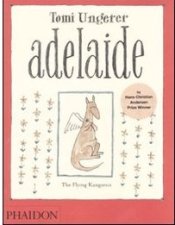

Tomi Ungerer, best known for his children's books—and his erotic and political illustrations—is back in the United States after a nearly 15 year absence. The French illustrator has a few good reasons to return: Phaidon is republishing eight of his books and the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art in Massachusetts is celebrating his upcoming 80th birthday with a retrospective exhibition of his works, which opens on June 18. That's not bad, considering that his political views and racy drawings so alarmed publishers that years ago they let his catalog go out of print. SLJ sat down with Ungerer, the author and illustrator of the bestselling classics Moon Man and The Three Robbers, to talk about why he's often the target of controversy, his love of libraries, and how it feels to visit the Big Apple again after all these years. What's it like being on U.S. soil again? I feel like the Moon Man coming back to Earth for the second time. I was apprehensive after so many years coming back to New York City, but I realize that apart from a few skyscrapers, which by the way I loathe, it hasn't changed. Does New York hold a special place in your heart? I love the spirit of New York. I have been asking myself, why are some towns dynamic? I realize that one feels liberated when one comes to New York City, and anything is possible. I arrived here with $60 in my pocket at the age of 25, and within a year I had my first book, The Mellops Go Flying (Harper & Row, 1957), published. A few years later, I bought my first brownstone on Commerce Street. It was the only house in New York City that was painted pink, and it was Aaron Burr's house, the bad man of American politics. This trip has another purpose because I am writing about my New Yo rk years. It is one thing to have all your memories, but I came here to put things into perspective. I had to find a screen—and New York is my screen with my past being projected upon it. Do you have a favorite among all your books? Yes, there is one book with which I am really pleased, and it has never been published in the United States. It is Warteraum (Diogenes Verlag, 1985), which contains drawings and paintings of the old objects at a sanitarium that Thomas Mann's wife stayed in and which I visited, called Hotel Schatzalp. I was able to interpret Thomas Mann's style in my drawings. In it, I inverted death and made death white instead of black. I don't normally like my books. I have a lot of "chips on my shoulder," but I think every book is a "block" rather than a "chip." Whenever I do a book, I really get into it and am enthusiastic, but the moment it is finished I am deflated. I don't want to look at it. It embarrasses me, but my books are translated into 330 languages so they've got to have something. You're having a few republished in the United States. When Phaidon told me that they were republishing Adelaide (Phaidon, 2011), I was totally embarrassed because look how badly I drew in those days. [Originally published in 1980, the book is about a flying kangaroo.] I have been developing my drawing all my life, studying anatomy. Now I look at my drawing, and I say, "My God it is really all right," because the more you develop your technique, the more your lose your innocence. I must say the fact that those drawings are not perfect illustrations is because I was still trying to find a way to develop my skills. Why do you

rk years. It is one thing to have all your memories, but I came here to put things into perspective. I had to find a screen—and New York is my screen with my past being projected upon it. Do you have a favorite among all your books? Yes, there is one book with which I am really pleased, and it has never been published in the United States. It is Warteraum (Diogenes Verlag, 1985), which contains drawings and paintings of the old objects at a sanitarium that Thomas Mann's wife stayed in and which I visited, called Hotel Schatzalp. I was able to interpret Thomas Mann's style in my drawings. In it, I inverted death and made death white instead of black. I don't normally like my books. I have a lot of "chips on my shoulder," but I think every book is a "block" rather than a "chip." Whenever I do a book, I really get into it and am enthusiastic, but the moment it is finished I am deflated. I don't want to look at it. It embarrasses me, but my books are translated into 330 languages so they've got to have something. You're having a few republished in the United States. When Phaidon told me that they were republishing Adelaide (Phaidon, 2011), I was totally embarrassed because look how badly I drew in those days. [Originally published in 1980, the book is about a flying kangaroo.] I have been developing my drawing all my life, studying anatomy. Now I look at my drawing, and I say, "My God it is really all right," because the more you develop your technique, the more your lose your innocence. I must say the fact that those drawings are not perfect illustrations is because I was still trying to find a way to develop my skills. Why do you write books for children? I write children's books for entertainment. It is a need I have. I am my own child, and I cannot escape it. Why do you think you've often been the target of controversy? I have had controversy all my life. Sometimes I created it. In a way, I am still an angry young man. When I am angry I don't hold my words. When I have a mission, like many missionaries, I can become caught up in it. Anger is the worst trait I have. Anger can be blind. When anger is blind with me, I can be perfectly unfair, stupid even. If I am angry in a cool way, that is another matter. As they say in French, "Anger is a meal that should be eaten cold." You've said you were disturbed by the many social ills in the United States, like segregation and the Vietnam War. What do you recall of that time? I grew up under Nazi occupation. With the war over, I thought it was all behind, and suddenly I come to America and find that there is a parallel movement that still exists. In 1957, I went to Amarillo, TX, where my girlfriend's father was the sheriff. It was there that witnessed segregation and became involved with civil rights. Also, when I arrived in the United States the Korean War was going on, a war that was completely justified. On the other hand, the war in Vietnam was something different because it was uncalled for. I really engaged myself in protesting the war. I created posters that have become classics. I printed and paid for them myself. They were distributed through a chain of poster shops. As a result of those posters, I worked with Stanley Kubrick on the film Dr. Strangelove.

write books for children? I write children's books for entertainment. It is a need I have. I am my own child, and I cannot escape it. Why do you think you've often been the target of controversy? I have had controversy all my life. Sometimes I created it. In a way, I am still an angry young man. When I am angry I don't hold my words. When I have a mission, like many missionaries, I can become caught up in it. Anger is the worst trait I have. Anger can be blind. When anger is blind with me, I can be perfectly unfair, stupid even. If I am angry in a cool way, that is another matter. As they say in French, "Anger is a meal that should be eaten cold." You've said you were disturbed by the many social ills in the United States, like segregation and the Vietnam War. What do you recall of that time? I grew up under Nazi occupation. With the war over, I thought it was all behind, and suddenly I come to America and find that there is a parallel movement that still exists. In 1957, I went to Amarillo, TX, where my girlfriend's father was the sheriff. It was there that witnessed segregation and became involved with civil rights. Also, when I arrived in the United States the Korean War was going on, a war that was completely justified. On the other hand, the war in Vietnam was something different because it was uncalled for. I really engaged myself in protesting the war. I created posters that have become classics. I printed and paid for them myself. They were distributed through a chain of poster shops. As a result of those posters, I worked with Stanley Kubrick on the film Dr. Strangelove. I've heard you say a few interesting things during this recent trip to New York. Can you please elaborate on them? "I don't take curves I take corners"? What I meant is giving destiny a destination. People ask me why I left New York. I met [my wife] Yvonne, and one day I said. "Let's get out of here," and we moved to Nova Scotia. When we decided to have children—and if you read my book, Far Out isn't Far Enough Life in the Back of Beyond [recently released by Phaidon, 2011], you can tell that Nova Scotia wasn't a place to raise a family. So we moved to Ireland. "Nature is your greatest inspiration"? I would say so. I was brought up that way. For my mother and my father, god was nature. Nature was a manifestation of god. For my mother, the woods was our church. We prayed every day, we were very Protestant, but rarely went to church. My mother would say it is better for us to go to the woods than to church. "I rather a barricade than a traffic jam"? Oh, that is one of my sayings. My career would be boring if I had the same style all the time. This maybe is why I have an inferiority complex. I feel like a bee going from flower to flower, from style to style, from one idea to another, while there are other artists who stick by their one style. My life would be boring if I didn't engage myself in many causes. "Lucky I can both draw and write"? Yes, that is a fine

I've heard you say a few interesting things during this recent trip to New York. Can you please elaborate on them? "I don't take curves I take corners"? What I meant is giving destiny a destination. People ask me why I left New York. I met [my wife] Yvonne, and one day I said. "Let's get out of here," and we moved to Nova Scotia. When we decided to have children—and if you read my book, Far Out isn't Far Enough Life in the Back of Beyond [recently released by Phaidon, 2011], you can tell that Nova Scotia wasn't a place to raise a family. So we moved to Ireland. "Nature is your greatest inspiration"? I would say so. I was brought up that way. For my mother and my father, god was nature. Nature was a manifestation of god. For my mother, the woods was our church. We prayed every day, we were very Protestant, but rarely went to church. My mother would say it is better for us to go to the woods than to church. "I rather a barricade than a traffic jam"? Oh, that is one of my sayings. My career would be boring if I had the same style all the time. This maybe is why I have an inferiority complex. I feel like a bee going from flower to flower, from style to style, from one idea to another, while there are other artists who stick by their one style. My life would be boring if I didn't engage myself in many causes. "Lucky I can both draw and write"? Yes, that is a fine  balance, because what you cannot express it in one way, you can do it in another. Especially with children's books, all the great children's books were written and drawn by the same person. You've been described as brutal, nasty, and diabolic. Is that fair? A great deal of my books are very hard. I just show society the way I see it. I am really basically a social critic. The books that I've done for the last 50 years, like Babylon (Diogenes, 1979), look at the ills of the world. I had to hit hard if I wanted to get my ideas across. Tell us about your editor, the famed Ursula Nordstrom. Ursula is the one who really got me started. I was working for magazines and became very sick with a relapse of a lung problem. I went to the hospital. When I told them I didn't have any money, I was told to "Go back to where you came from." That was the two sides of America at that time. Sick, I went to a scheduled appointment with Ursula. At the meeting, I passed out, and they put me on the couch. There, in the office shaking and crying, Ursula took care of me. She liked my drawings and gave me a $500 advance. With that money, I was able to take care of my medical condition. I had a children's book already written abou

balance, because what you cannot express it in one way, you can do it in another. Especially with children's books, all the great children's books were written and drawn by the same person. You've been described as brutal, nasty, and diabolic. Is that fair? A great deal of my books are very hard. I just show society the way I see it. I am really basically a social critic. The books that I've done for the last 50 years, like Babylon (Diogenes, 1979), look at the ills of the world. I had to hit hard if I wanted to get my ideas across. Tell us about your editor, the famed Ursula Nordstrom. Ursula is the one who really got me started. I was working for magazines and became very sick with a relapse of a lung problem. I went to the hospital. When I told them I didn't have any money, I was told to "Go back to where you came from." That was the two sides of America at that time. Sick, I went to a scheduled appointment with Ursula. At the meeting, I passed out, and they put me on the couch. There, in the office shaking and crying, Ursula took care of me. She liked my drawings and gave me a $500 advance. With that money, I was able to take care of my medical condition. I had a children's book already written abou t a family of pigs and a butcher. She told me that it was a bit harsh for American children and suggested that I write another story with the same family of pigs. I went back to my basement apartment and wrote the Mellops Go Flying. Ursula was wonderful. She was a rabble- rouser, and she and I loved to stir the pot. I met Maurice Sendak through Ursula and brought some of my friends to meet her like Shel Silverstein and Edward Gorey. Do you ever think about your legacy? My legacy is ensured by the fact that I have a museum, which is absolutely unique in France. The Musée Tomi Ungerer, devoted exclusively to my work, opened in France in 2007, it has 13,000 pieces of my artwork and my whole library. What message do you have for your American fans? Personally, libraries are the most important institution in a democratic society. Libraries are places for all ages. Personally, I could not live without books, and I have learned much from them. Please go to the library and read books to your children because a book is a bridge between the one who reads it and the one who listens to it.

t a family of pigs and a butcher. She told me that it was a bit harsh for American children and suggested that I write another story with the same family of pigs. I went back to my basement apartment and wrote the Mellops Go Flying. Ursula was wonderful. She was a rabble- rouser, and she and I loved to stir the pot. I met Maurice Sendak through Ursula and brought some of my friends to meet her like Shel Silverstein and Edward Gorey. Do you ever think about your legacy? My legacy is ensured by the fact that I have a museum, which is absolutely unique in France. The Musée Tomi Ungerer, devoted exclusively to my work, opened in France in 2007, it has 13,000 pieces of my artwork and my whole library. What message do you have for your American fans? Personally, libraries are the most important institution in a democratic society. Libraries are places for all ages. Personally, I could not live without books, and I have learned much from them. Please go to the library and read books to your children because a book is a bridge between the one who reads it and the one who listens to it. RELATED

RECOMMENDED

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!