2018 School Spending Survey Report

Jump Back, Paul | Sally Derby on Paul Laurence Dunbar

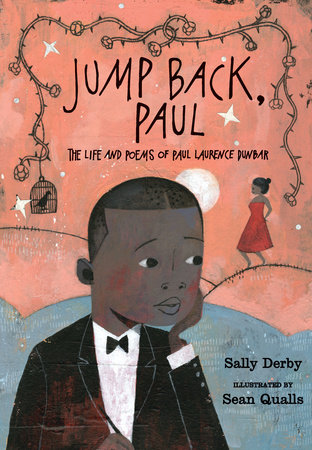

In "Jump Back, Paul," Sally Derby introduces a new generation of readers to the life, times, and work of this extraordinary talent.

During the late 19th and well into the 20th century, the poetry of Paul Laurence Dunbar was immensely popular: read in homes, recited by schoolchildren, and praised by critics. While today's readers may not be as familiar with the work of this prolific author of poetry, novels, and plays, many recognize the first line of his poem "Sympathy," "I know what the caged bird feels, alas!" as the inspirational source of the title of Maya Angelou's autobiography, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. In Jump Back, Paul (Candlewick, Sept. 2015, Gr 5-8), illustrated by Sean Qualls, Sally Derby assumes the voice of a storyteller as she introduces a new generation of readers to the life, times, and work of this extraordinary talent. How and when were you introduced to the poetry of Paul Laurence Dunbar? My fourth grade teacher, Mrs. Patterson, who was always telling us we should have “gumption,” was fond of reading poems with messages that she thought would make us think—and a number of Dunbar’s poems, including “Keep A-Pluggin’ Away,” fit the bill. In our Dayton, Ohio suburb, we were proud to learn that Dunbar had also been a Daytonian. In Jump Back, Paul you adopt the voice of a storyteller and weave in many of Dunbar’s poems in telling his story. What led you to those decisions? When I talk to a classroom, all I need to say is, “Now, I want to tell you a little story,” and a noticeable hush falls. Those are magic words, and since time immemorial that is the way culture has been passed on. (No one can resist a good story.) During his lifetime and for some years thereafter Dunbar’s popularity was immense, his poems well-known. But after the Harlem Renaissance, he fell out of style and has never since regained as wide an audience. I wanted to reintroduce Dunbar, to restore the rich heritage of insight, humor, and sympathy he left at the end of his tragically short life. I’m not sure exactly how many poems he wrote, but there were hundreds, so selecting those those to include was a challenge. I wanted each to have a relationship to the surrounding text, I wanted to show Dunbar's astonishing range and mastery of form, and to incorporate poems that would appeal to young readers. If I had included every one I wanted to, there would have been no space for Sean Qualls’s illustrations, and that would have been a shame. In addition to his life experiences, many of Dunbar’s poems were inspired by family stories—of his parents and grandparents, and his father’s Civil War stories. What were some of his other themes? Many of his later poems, of course, were inspired by his love for [his wife] Alice, by their courtship, marriage, and divorce. After meeting Frederick Douglass at the World’s Fair in Chicago, more of Dunbar's poems were concerned racial injustice and the growing “new slavery” of Jim Crow laws. But his poems were always written from the viewpoint of ordinary people. Dunbar's decision to often write in dialect, while in many ways a practical one, resulted from his dislike of verses by inferior white versifiers who tried to approximate black dialect by mangling spelling and syntax. His mother seems to have been an incredible woman, whose sacrifices and aspirations for her son had an enormous influence on him. The importance of Matilda Dunbar in her son's life cannot be overestimated. She deserves a biography of her own and trying to find source material enough for a book about her would be a fascinating and challenging project. I’d love to see Dunbar scholar and indefatigable researcher Dr. Joanne M. Braxton undertake it. Paul Dunbar was the only African American student in his class at Central High School in Dayton, Ohio. What was that experience like for him? By all accounts, Paul was well-liked and respected by both students and teachers, who nicknamed him “Deacon Dunbar.” He was good friends with Orville and Wilbur Wright, of later aviation fame. He was elected president of the debating society and chosen to write the words for the class graduation song. He was the only African American in his class, but his good friend Bud Burns, who became Dayton’s first black doctor, was only a year behind him. Despite having been published and the recipient of local honors during his high school years, it wasn’t until a teacher recognized him working an elevator in downtown Dayton a few years later that Dunbar received one of his first real breaks, had a chance perform his work and publish again, and earned some fan mail, including a letter from the poet James Whitcomb Riley of “Little Orphant Annie” fame. Leaving high school is a difficult transition for many, and for Dunbar it was a rude awakening. The day after the graduation ceremony he was suddenly no longer a senior walking familiar halls in the company of people who knew and admired him, but just another black youth looking for a job. He fully expected to be hired by the local paper, which had printed several of his poems, but he learned in short order that the newsroom had no place him. Although he was not particularly robust, manual labor was the only sort of work open to him. Dunbar was masterful in capturing the dialect of the antebellum South, and his poems written in dialect were some of his most popular. You mention in the book that you believe he did not feel these were minor poems, rather “renderings of the rich and varied black language and culture" [he] knew so well. To be candid, this touches on a subject I feel passionately about. In the United States, the ability to use “standard” or “polite” English is basic to the achievement of success in most fields. But that does not automatically make this speech superior to dialect or any other speech pattern common to a particular group. The speech is best that best conveys the speaker’s meaning. We all have different speech patterns even different vocabularies we use depending on whom we are with. What teenager uses the same expressions talking to a parent that he uses when talking to a friend? We need to remember that “different” is not a synonym for either “better” or “worse,” and that exploring differences without prejudging them expands our knowledge and our understanding both of others and of ourselves. Despite the fact that his dialect poems were well-regarded, they were a point of contention between Dunbar and his wife. In many ways this disagreement between Dunbar and his wife reflects the difference between how they viewed their racial identity. Alice was willing to pass as white when it suited her. On the other hand, while Paul acknowledged that being black [limited his opportunities], he refused to consider whites superior. Dunbar was alive when African Americans in the South lived in fear of the Klan, and when the Plessy vs. Ferguson (1896) decision ushered in more Jim Crow laws and practices. You note that he was criticized for insufficient “shouting,” but also that he “didn’t let caution silence him.” Can you expand on that? In Jump Back Paul I did not discuss the prose writings in which he speaks eloquently in defense of African Americans and their achievements but anyone who reads “The Haunted Oak,” "Frederick Douglass," or “To the South” with its pointed subtitle “On Its New Slavery” should recognize that this is bold writing from someone who knows that his life and livelihood are under constant threat and that if he offends the wrong person, the dominant society will offer him little in the way of either protection or redress. To what do you attribute the waning of his popularity in the latter half of the 20th century? All writers hoping to support themselves have to struggle with their desire to write what and as they please with their need to attract and hold onto readers. In view of this, some black critics during the Harlem Renaissance asserted that Dunbar wrote his dialect poetry, admittedly more widely popular than that in standard English, only to increase sales to whites, who formed the bulk of the book-buying public. Poet James Weldon Johnson (“God’s Trombones”), who claimed to be Dunbar’s friend, actually said that he thought Dunbar was ashamed of his use of dialect. This view prevailed until newer scholars and critics, delving more deeply, began to notice the artistry of Dunbar’s dialect writing and rediscovered some of his own remarks on the subject. Did your research yield any surprises? I was frankly astonished to discover how great Dunbar’s popularity was during his life. On a more personal note, I was amazed to discover how much I like doing research.

During the late 19th and well into the 20th century, the poetry of Paul Laurence Dunbar was immensely popular: read in homes, recited by schoolchildren, and praised by critics. While today's readers may not be as familiar with the work of this prolific author of poetry, novels, and plays, many recognize the first line of his poem "Sympathy," "I know what the caged bird feels, alas!" as the inspirational source of the title of Maya Angelou's autobiography, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. In Jump Back, Paul (Candlewick, Sept. 2015, Gr 5-8), illustrated by Sean Qualls, Sally Derby assumes the voice of a storyteller as she introduces a new generation of readers to the life, times, and work of this extraordinary talent. How and when were you introduced to the poetry of Paul Laurence Dunbar? My fourth grade teacher, Mrs. Patterson, who was always telling us we should have “gumption,” was fond of reading poems with messages that she thought would make us think—and a number of Dunbar’s poems, including “Keep A-Pluggin’ Away,” fit the bill. In our Dayton, Ohio suburb, we were proud to learn that Dunbar had also been a Daytonian. In Jump Back, Paul you adopt the voice of a storyteller and weave in many of Dunbar’s poems in telling his story. What led you to those decisions? When I talk to a classroom, all I need to say is, “Now, I want to tell you a little story,” and a noticeable hush falls. Those are magic words, and since time immemorial that is the way culture has been passed on. (No one can resist a good story.) During his lifetime and for some years thereafter Dunbar’s popularity was immense, his poems well-known. But after the Harlem Renaissance, he fell out of style and has never since regained as wide an audience. I wanted to reintroduce Dunbar, to restore the rich heritage of insight, humor, and sympathy he left at the end of his tragically short life. I’m not sure exactly how many poems he wrote, but there were hundreds, so selecting those those to include was a challenge. I wanted each to have a relationship to the surrounding text, I wanted to show Dunbar's astonishing range and mastery of form, and to incorporate poems that would appeal to young readers. If I had included every one I wanted to, there would have been no space for Sean Qualls’s illustrations, and that would have been a shame. In addition to his life experiences, many of Dunbar’s poems were inspired by family stories—of his parents and grandparents, and his father’s Civil War stories. What were some of his other themes? Many of his later poems, of course, were inspired by his love for [his wife] Alice, by their courtship, marriage, and divorce. After meeting Frederick Douglass at the World’s Fair in Chicago, more of Dunbar's poems were concerned racial injustice and the growing “new slavery” of Jim Crow laws. But his poems were always written from the viewpoint of ordinary people. Dunbar's decision to often write in dialect, while in many ways a practical one, resulted from his dislike of verses by inferior white versifiers who tried to approximate black dialect by mangling spelling and syntax. His mother seems to have been an incredible woman, whose sacrifices and aspirations for her son had an enormous influence on him. The importance of Matilda Dunbar in her son's life cannot be overestimated. She deserves a biography of her own and trying to find source material enough for a book about her would be a fascinating and challenging project. I’d love to see Dunbar scholar and indefatigable researcher Dr. Joanne M. Braxton undertake it. Paul Dunbar was the only African American student in his class at Central High School in Dayton, Ohio. What was that experience like for him? By all accounts, Paul was well-liked and respected by both students and teachers, who nicknamed him “Deacon Dunbar.” He was good friends with Orville and Wilbur Wright, of later aviation fame. He was elected president of the debating society and chosen to write the words for the class graduation song. He was the only African American in his class, but his good friend Bud Burns, who became Dayton’s first black doctor, was only a year behind him. Despite having been published and the recipient of local honors during his high school years, it wasn’t until a teacher recognized him working an elevator in downtown Dayton a few years later that Dunbar received one of his first real breaks, had a chance perform his work and publish again, and earned some fan mail, including a letter from the poet James Whitcomb Riley of “Little Orphant Annie” fame. Leaving high school is a difficult transition for many, and for Dunbar it was a rude awakening. The day after the graduation ceremony he was suddenly no longer a senior walking familiar halls in the company of people who knew and admired him, but just another black youth looking for a job. He fully expected to be hired by the local paper, which had printed several of his poems, but he learned in short order that the newsroom had no place him. Although he was not particularly robust, manual labor was the only sort of work open to him. Dunbar was masterful in capturing the dialect of the antebellum South, and his poems written in dialect were some of his most popular. You mention in the book that you believe he did not feel these were minor poems, rather “renderings of the rich and varied black language and culture" [he] knew so well. To be candid, this touches on a subject I feel passionately about. In the United States, the ability to use “standard” or “polite” English is basic to the achievement of success in most fields. But that does not automatically make this speech superior to dialect or any other speech pattern common to a particular group. The speech is best that best conveys the speaker’s meaning. We all have different speech patterns even different vocabularies we use depending on whom we are with. What teenager uses the same expressions talking to a parent that he uses when talking to a friend? We need to remember that “different” is not a synonym for either “better” or “worse,” and that exploring differences without prejudging them expands our knowledge and our understanding both of others and of ourselves. Despite the fact that his dialect poems were well-regarded, they were a point of contention between Dunbar and his wife. In many ways this disagreement between Dunbar and his wife reflects the difference between how they viewed their racial identity. Alice was willing to pass as white when it suited her. On the other hand, while Paul acknowledged that being black [limited his opportunities], he refused to consider whites superior. Dunbar was alive when African Americans in the South lived in fear of the Klan, and when the Plessy vs. Ferguson (1896) decision ushered in more Jim Crow laws and practices. You note that he was criticized for insufficient “shouting,” but also that he “didn’t let caution silence him.” Can you expand on that? In Jump Back Paul I did not discuss the prose writings in which he speaks eloquently in defense of African Americans and their achievements but anyone who reads “The Haunted Oak,” "Frederick Douglass," or “To the South” with its pointed subtitle “On Its New Slavery” should recognize that this is bold writing from someone who knows that his life and livelihood are under constant threat and that if he offends the wrong person, the dominant society will offer him little in the way of either protection or redress. To what do you attribute the waning of his popularity in the latter half of the 20th century? All writers hoping to support themselves have to struggle with their desire to write what and as they please with their need to attract and hold onto readers. In view of this, some black critics during the Harlem Renaissance asserted that Dunbar wrote his dialect poetry, admittedly more widely popular than that in standard English, only to increase sales to whites, who formed the bulk of the book-buying public. Poet James Weldon Johnson (“God’s Trombones”), who claimed to be Dunbar’s friend, actually said that he thought Dunbar was ashamed of his use of dialect. This view prevailed until newer scholars and critics, delving more deeply, began to notice the artistry of Dunbar’s dialect writing and rediscovered some of his own remarks on the subject. Did your research yield any surprises? I was frankly astonished to discover how great Dunbar’s popularity was during his life. On a more personal note, I was amazed to discover how much I like doing research.  Listen to Sally Derby reveal the story behind Jump Back, Paul, courtesy of TeachingBooks.net.

Listen to Sally Derby reveal the story behind Jump Back, Paul, courtesy of TeachingBooks.net. RELATED

RECOMMENDED

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!