Rogues and Riches on the Sea | Martin W. Sandler's "The Whydah"

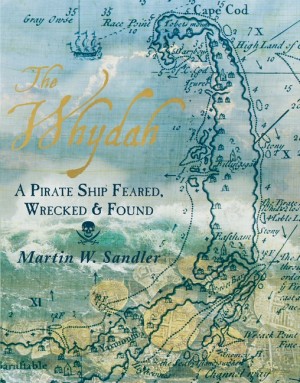

Listen to Martin W. Sandler reveal the story behind The Whydah: A Pirate Ship Feared, Wrecked, and Found, courtesy of TeachingBooks.net. Launched in 1716, the Whydah Gally was built to carry large cargoes “both material and human”— and for speed. But not long out on the seas, the vessel was overtaken by Sam Bellamy, one of the most brazen pirate captains that sailed the Caribbean and the Atlantic Coast. But Bellamy's plundering ended abruptly when his treasure-laden ship went down in a storm off the coast of Cape Cod in 1717. Martin W, Sandler's fascinating account of Bellamy's adventures aboard The Whydah: A Pirate Ship Feared, Wrecked, and Found (Candlewick, Mar. 2017; Gr 6–10) combines early 18th-century history and legend with stories of real-life rogues and riches. The remarkable discovery of the Whydah in 1985 marked the first time a pirate ship was recovered, and its ongoing excavation continues to yield surprising information about the era and life on the sea.

Listen to Martin W. Sandler reveal the story behind The Whydah: A Pirate Ship Feared, Wrecked, and Found, courtesy of TeachingBooks.net. Launched in 1716, the Whydah Gally was built to carry large cargoes “both material and human”— and for speed. But not long out on the seas, the vessel was overtaken by Sam Bellamy, one of the most brazen pirate captains that sailed the Caribbean and the Atlantic Coast. But Bellamy's plundering ended abruptly when his treasure-laden ship went down in a storm off the coast of Cape Cod in 1717. Martin W, Sandler's fascinating account of Bellamy's adventures aboard The Whydah: A Pirate Ship Feared, Wrecked, and Found (Candlewick, Mar. 2017; Gr 6–10) combines early 18th-century history and legend with stories of real-life rogues and riches. The remarkable discovery of the Whydah in 1985 marked the first time a pirate ship was recovered, and its ongoing excavation continues to yield surprising information about the era and life on the sea.

You paint a vivid picture of the capture of a cargo ship by pirates. By all accounts Sam Bellamy, captain of the Whydah, was absolutely fearless—at times seizing four ships in a day. How was this possible?

He was absolutely fearless, but it helped that those merchant captains and crews were absolutely petrified of pirates. The men who were sailing these merchant ships weren’t getting paid enough to risk their lives to save the cargo, so the minute the pirate flag went up—especially when they saw it was the Whydah—they gave in.

Despite the brutality meted out by pirates, a code of law was honored on the ship as well as “a spirit of democracy and equality.” Can you elaborate?

In all my research for the book, this was what I found the most interesting. Pirates lived under the greatest democracy the world knew at the time. They elected their captain and could vote him out at any time. Anyone was welcome to go into the captain’s quarters and share what he had. If there weren’t enough hammocks to go around, everyone slept on deck, including the captain. And crews took a vote on whether they were going to go after another vessel.

I was surprised to learn about the entertainment on the Whydah—the mention of musicians that worked six days per week, and the playacting—including one skit about pirate life that so roused the audience that they jumped up and attacked the performers (killing one).

[My earlier work] Resolute: The Epic Search for the Northwest Passage and John Franklin, and the Discovery of the Queen's Ghost Ship was the first time I wrote about life at sea and one thing that fascinated me was that the ships that went out searching for the Northwest Passage had costumes, make-up, scripts, everything [they needed to put on a play], knowing that the sailors might be stuck in the ice for a year, maybe two. Life at sea, for all the supposed adventure and swashbuckling, was a damn boring life. For pirates, the time between captures and chases could be weeks and even months. The Whydah crew kept themselves entertained. There was another aspect to the role of musicians on the Whydah. If, one chance in a million, the pirate flag didn’t make the other ship surrender, the pirates attacked. They screamed, yelled, and played the most cacophonous music possible to scare the merchant ship’s crew out of their wits. The musicians weren’t just entertaining the crew at night; they were also part of any attack that might take place.

Even Cotton Mather makes an appearance in this story.

He’s a fascinating character, and I was very happy to get him in, because I think I was able to give him more dimension; he’s usually portrayed as a narrow-minded bigot. Mather’s involvement came with the trial of the Whydah pirates. Much of the public found these figures colorful, but government officials were outraged at what they were doing—and getting away with. After the Whydah pirates were captured, the government wanted to make them examples by punishing them publicly. Their trial was more than a trial of these particular men; it was a display on the evils of piracy—and what would happen to anyone who became a pirate. It's a pretty gruesome fact, but when they hung these men, the bodies were left hanging for two years. Cotton Mather's goal was to get these guys to confess their sins. And they actually did, thinking it would earn them leniency—boloney. But Mather visited them in their cells, and insisted they confess. He’s was still asking them to do so when they walked to their execution—“confess your sins, confess your sins.”

Shipwrecks have been referred to as time capsules. The Whydah was the first pirate ship discovered and excavated. What have we learned about the period and pirates from the 200,000 artifacts recovered from it?

I could talk for 62 hours about this! This book didn’t start out as a book about the Whydah. It was based on a sentence I wrote in an earlier book: “the vast ocean floor is the greatest museum in the world.” Even more than artifacts on land, the entire history of the world is preserved on the ocean floor. So this started out as a book about marine archaeology. The artifacts that are being recovered from the Whydah have been hugely informative. From the wreck, we’re learning more about the way pirates lived, dressed, and some of advanced tools they had, such as medical syringes; history had it that those arrived until 100 years later. “Time capsule” is the perfect word for it.

You offer an incredible amount of information about life on the Whydah. In addition to the artifacts, what archival records exist about the ship and life on the sea during the period?

Before this book, there has been very little written about the Whydah. Barry Clifford, who found the wreck, wrote two books—The Pirate Prince and Expedition Whydah—and there was Arthur T. Vanderbilt’s Treasure Wreck. These books concentrate on the excavation of the ship. I cover that as well, but what I really wanted to tell was the story of the ship itself—how fascinating it is it starts as a slave ship, for example. There’s some archival material, but there’s not a lot. We have all the diaries and journals of Cyprian Southack, who was assigned by the Massachusetts Bay Province to protect the shipwreck from looters. They tell quite a bit about what happened when he went looking for the looters. But that’s very narrow. The one book I would cite was written a long time ago: A General History of the Pyrates. When it was published, it was credited to a “Captain Christopher Johnson.” It’s fascinating because it tells the story of practically every major pirate of the day and his voyages. Included is the story of Sam Bellamy and the Whydah. By the late 1800s, nobody had been able to find out anything about Christopher Johnson. People started putting things together, and it became obvious—Johnson had never lived, and this book was written by Daniel Defoe. The editions that have come out since the 1930s and 40s have been credited to Defoe. It’s the best archival stuff there is.

What is it about pirate stories that they continue to appeal to our imagination today?

I think the main draw of these stories is that above everything else, these men became pirates because they were looking for freedom—freedom from oppression—and many people are still seeking that today.

Listen to Martin W. Sandler reveal the story behind The Whydah: A Pirate Ship Feared, Wrecked, and Found, courtesy of TeachingBooks.net.

Listen to Martin W. Sandler reveal the story behind The Whydah: A Pirate Ship Feared, Wrecked, and Found, courtesy of TeachingBooks.net.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!