In a Meme Culture, How To Spark Critical Thinking About Images

Visual literacy demands increasingly sophisticated tools to expand kids' critical skills.

|

On the Internet: A pasted-in bear lurks behind a clueless fisherman;

|

Related Article: |

This fall, when the White House released a video of CNN chief White House correspondent Jim Acosta appearing to hit a White House intern, the video became emblematic of the political battle over truth. Even as a video expert took to social media in a widely shared tweet that broke down the ways in which the video had clearly been altered, the White House press secretary stood by the video that was shared from her official Twitter account.

Suddenly, a live interaction watched all over the country became a vehicle for another partisan tug-of-war. People saw what they wanted to see.

Suddenly, a live interaction watched all over the country became a vehicle for another partisan tug-of-war. People saw what they wanted to see.

In our age of lightning-fast image sharing and easy editing, images have become highly vulnerable to distortion—with profound impact. Along with that rapid shift, visual literacy has become a critical skill for young people. With today’s students scrolling through Instagram posts and memes, and watching YouTube videos on demand, often all at the same time, knowing how to parse what they see is vital.

Visual literacy involves the ability to observe an image or video and recognize visual strategies, possible alterations, and their effect on meaning. Every 60 seconds, 500 hours of video are uploaded to YouTube, along with 3.3 million Facebook posts, according to SmartInsights.com. Reports released by the Senate Intelligence Committee recently confirmed that a trove of Facebook and Instagram images were posted by Russian trolls in an effort to influence American opinion during the 2016 presidential election. Meanwhile, deep fake technology—artificial intelligence that can synthesize audio, faces, photos, and videos, effectively swapping someone else’s voice and face into a video—is on the rise. In a widely circulate deep fake video of Barack Obama, for example, it is virtually impossible for the lay viewer to detect that image and sound were altered.

In an increasingly image-saturated culture, humans still have an innate trust that what we are seeing can be believed, says Hany Farid, professor of computer science at Dartmouth College and a leading expert on video manipulation. Thomas Jefferson once said that the health of democracy depends upon an informed electorate, but it’s hard to be informed when the veracity of what we see with our own eyes becomes suspect.

|

Altered photos (l. to r.): An image shared by Donald Trump Jr. changed a CNN graphic to show a 50 percent approval rating for the president; a falsified video interview with U.S. Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez; a blue whale inserted in a photo of a surfer riding a huge wave. |

Slow down and apply reason

For this generation, the news is social, visual, and fast. Criteria that educators use to assess credibility aren’t so effective with newer social media forms, say 56 percent of the nearly 6,000 college-age respondents in a Project Information Literacy (PIL) report from October 2018.

“The average person, who is not a tech expert, often feels like it’s within their skill set to do an armchair forensic analysis of videos,” says Farid. “The problem is that images and videos are sometimes weird. Often, people jump to conclusions based on things that are unusual but not due to tampering.”

While there aren’t any easy solutions yet, developing technologies will allow a digital signature using a blockchain, meaning that the original image will have a timestamp at the time of capture and can be compared with any subsequent images in order to detect manipulation. In a couple of years, Farid predicts, this tech will be available for use on devices, either through an app or directly on smartphone cameras.

“Not everything you see on the Internet is true,” says Farid. “I cannot believe I have to say this over and over again. Before you share, retweet, like, take a breath. We’re moving way too fast online, and it’s not good for us personally—and certainly not good for our democracy.”

Visual Thinking Strategies (VTS), a nonprofit promoting visual literacy in schools through a curriculum designed to develop critical thinking skills, strongly advocates slowing down. Students in Katharine Amaral’s social studies class at Gilbert Stuart Middle School in Providence, RI, for example, are asked to look at an image. Really look at it, study it, discuss it, think about it, and look some more.

Amy Chase Gulden, a VTS educator, shows Amaral’s students a painting of a woman sitting serenely in the woods. With her are a fox and a deer. The students look for a while. Then, taking their time, they start to discuss the image.

Students first recognize detail, such as that the image includes both a fox and a woman sitting calmly next to it. Second, students move to interpretive and narrative remarks, such as, “Why are the fox and the woman sitting next to each other?” Students then infer beyond what they see and, using their knowledge of the world, note that such a scenario would likely never happen. Reasoning and applying evidence, speculative thinking, and mental flexibility follow.

Ultimately, the students wonder if the image is Photoshopped.

“In this environment, expressing their opinion is risk-free. There’s no right or wrong answer,” says Amaral. “Visual Thinking Strategies helps foster an open mind and a new way to look at the same thing. We hold [students] accountable for their statements by asking for more detail. It’s important in the digital age to make sure people back up their opinions with information.”

Through pre- and post-tests, VTS has found that within 30 minutes of looking at and discussing an image, students advance through several levels of thought that develop critical thinking. VTS has documented the transfer of those skills gained just from looking for a little longer.

Generation meme

For a young generation that has grown up with memes, there’s nothing notable about merging information and entertainment in a moving picture. The combinations of image and words, and sometimes jokes, create shorthand punchlines, frequently related to current events. The PIL study found that 82 percent of students engage with memes weekly, enough to classify political memes as their own news category for the first time. “That’s how I find out what’s going on in the world.…Even fake news starts conversations,” noted one of the PIL study’s participants.

Does growing up surrounded by manipulated images make digital natives more capable of recognizing them? No, says Frank W. Baker, national media literacy educator and creator of the Media Literacy Clearinghouse.

Does growing up surrounded by manipulated images make digital natives more capable of recognizing them? No, says Frank W. Baker, national media literacy educator and creator of the Media Literacy Clearinghouse.

“They might be media savvy, but they’re not media literate,” says Baker. “They look at memes and pictures, immediately forward them on with no thought of who created them.”

Still, there is something to the idea of memes as a legitimate form of communication, says Baker. “Memes are like parody and make reference to something you need to be familiar with to understand,” he says. “If students are prepared for viewing a meme properly, they will still ask, ‘Who is the creator and what are they trying to communicate?’”

Go to the source

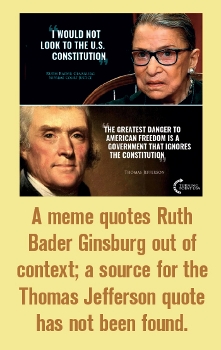

The News Literacy Project’s The Sift, a media literacy newsletter for educators, breaks down a meme picturing Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Thomas Jefferson side by side. Ginsburg is quoted as saying, “I would not look to the U.S. Constitution,” and Jefferson is quoted, “The greatest danger to American freedom is a government that ignores the Constitution.”

The intention of the meme is to portray Ginsburg as betraying the document upon which American governance is founded. The Sift provides a link to the Ginsburg quote, which is taken out of context, and finds no evidence that Jefferson ever said the quote above. Not all memes are false or misleading, but the fact that they are shorthand intended to convey a particular viewpoint means that they require additional due diligence and fact-checking original sources, says Baker.

As found with VTS, just learning the habit of taking the time to study an image or video can go a long way toward sharpening visual literacy. Similar to verifying a news article, verifying an image starts with slowing down and asking questions.

Designed for classroom use, The Sift analyzes viral rumors, fact-checks memes, and provides discussion fodder for classrooms every week, plus online tools teachers and students can use to do their sleuthing. The process prompts viewers to stop and ask: Where did I see that image of migrants making their way through Central America? What is the source?

Baker encourages tracing the source of a photograph, as one would for any news article, by investigating the “About” page of the website hosting the photo and interrogating URLs to make sure they are what they say they are. For instance, some URLs are designed to impersonate legitimate media organizations, but, upon closer inspection, are off by a few letters. Consider abcnews.com.co versus the actual website for ABC News, ABCNews.go.com. Fact-checking via sites including Snopes.com or FactCheck.org can also determine veracity. Additional questions to ask with photos and videos include: Is it part of a larger video production, or was it taken out of context? Triangulating the image or video can help answer those questions. In other words, compare it to the images appearing in other news sources to make sure they look the same.

Creators make better consumers

For many kids and adults, editing photos on a phone—by cropping, filtering, or marking up—is second nature. Doing this makes us students of visual literacy already. Everyone knows that adding a moody filter affects how an image will be seen. While it may be challenging for amateurs to break down an image or video the way experts did with the Acosta video, they can begin to understand how and why images are altered to impact perception.

Dana Carmichael, a middle school librarian in Whitefish, MT, starts her unit on video literacy by talking to kids about the ways social media photos and videos are edited. The discussions culminate with the kids creating a green screen project, putting themselves in a fantasy photo, such as a portraying a national football team player or standing at the gates of Harvard.

“The kids are all aware of what they can create in half an hour from their own bed using these tools at their disposal. Yet they’re all very trusting of other people’s photos they see online. If they build their own fake photo, maybe they’ll think twice about what they see online,” says Carmichael.

The art of presenting images is at the heart of everything TV production teacher Don Swanson does at Armstrong Jr-Sr High School in Kittanning, PA. His introduction to television class covers a variety of visual literacy concepts, from mise-en-scène to juxtaposition. Students are asked to think about how an image shot from different angles affects the way they perceive the subject.

Students work in the studios producing news shows. For one lesson, they study news clips that show a particular bias and are then asked to create their own biased segment. They ask leading interview questions and edit the piece to demonstrate their bias.

For another project, students discuss spin using an image of President Obama walking his dog. The students view the photo on NBC, where the caption describes Obama taking a break from work, and Fox News, which captions the same photograph by describing Obama walking his dog while the Middle East falls into turmoil.

After this activity, Swanson says kids began bringing election ads into the classroom and noting the way the opponent was portrayed in an unflattering photo.

“I want them to realize that media is a construct so they can negotiate it,” says Swanson. “If I do my job right, I will have ruined TV, movies, and news for them. It is the job of education to teach them to be critical consumers. By questioning, they will challenge the status quo. That in and of itself makes them better members of a democratic society.”

Education reporter Jennifer Snelling writes about teachers and students changing the world.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

TARA LANE BOWMAN

What is great about teaching meme literacy is that kids naturally are drawn to them (just like their parents!). Bonus: What you teach to library patrons, you can teach to your family/friends.Posted : Oct 19, 2019 01:39