Beyond the Brain: Dynamic School Libraries Encourage Thinking with an Extended Mind

The author of The Extended Mind writes how bustling library atmospheres can foster focus, comprehension, and creativity.

|

Kateryna Kovarzh/Getty Images |

Ryan Tahmaseb often has music playing at his school library’s circulation desk. “It’s not loud, and it’s almost always instrumental,” says Tahmaseb, director of library services at the Meadowbrook School, an independent school in Weston, MA. “But it does show that this isn’t the kind of library that worships silence.”

Nearby, a video monitor displays webcam footage of wild animals, streamed live from their habitats. Deeper inside the library, students might be engaging in peer teaching in the writing center, recording a podcast in the sound studio, or participating in a “listening party” organized to provide feedback to student authors.

The evolution of school libraries from sedate sanctuaries for the passive consumption of information to dynamic, active hubs like Tahmaseb’s has been underway for nearly a decade now across the country. The new model emphasizes hands-on learning, open flexible spaces, and highly social collaboration.

“This is very much not a ‘shushy’ place,” says Tahmaseb, also the author of the forthcoming book The 21st Century School Library (John Catt, Jan. 2022). “Students are huddled together working on a prototype,” Tahmaseb notes. “They’re interviewing classroom visitors. They’re tinkering in a makerspace. They’re using technology, books, found materials, sketchbooks, and more.”

One potentially useful interpretation of this school library evolution, borrowed from philosophy, would describe the current shift as a movement from a “brainbound” paradigm to an “extended mind” paradigm—one that treats mind-body connections, physical spaces, and social interactions as key elements of the thinking process.

|

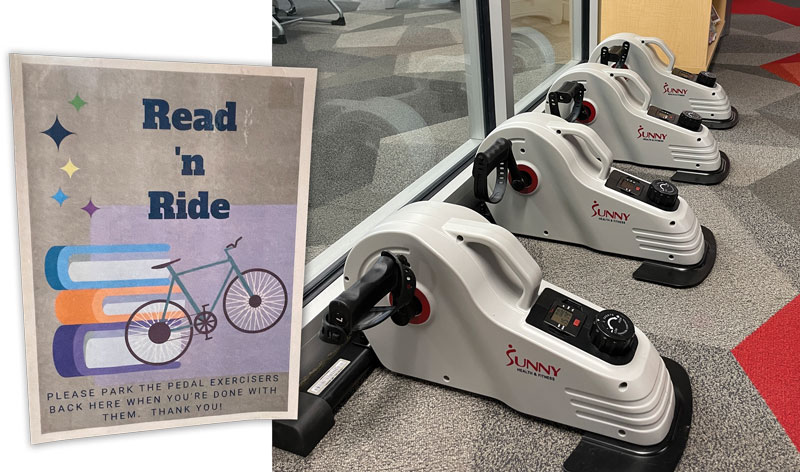

Pedalers at the Shepard Middle School library provide physical enagagement. |

The theory of the extended mind was first proposed by philosophers Andy Clark and David Chalmers in a 1998 article published in the journal Analysis. They opened with a provocative question: “Where does the mind stop and the rest of the world begin?” The mind does not stop at the skull, as we might have assumed; instead, the authors argued, it is spread across our bodies, our surroundings, and our relationships. Thinking processes aren’t limited to the brain and its neural resources, but rather incorporate a host of “extra-neural” resources—from expressive movements and gestures to well-designed physical spaces and vibrant exchanges with classmates and colleagues. These outside-the-brain resources effectively extend the mind’s capacity for intelligent thought.

In a subsequent elaboration of the theory, Clark—a professor of cognitive philosophy at Britain’s University of Sussex—juxtaposed the extended-mind perspective with the more conventional approach to thinking, which he called “brainbound.” The assumption that thinking is confined to the brain, he noted, forms the foundation of many of our beliefs and behaviors, especially in the educational realm. In accordance with the brainbound model, students are expected to remain still and quiet as they learn: not moving their bodies, not interacting with the space around them, and not socializing with the people nearby. It’s clear that the brainbound paradigm has also influenced the way many school libraries were traditionally designed and utilized.

Challenges to the brainbound model are growing more forceful today—invigorated by new research in biology, psychology, and cognitive science. The field of embodied cognition, for example, is demonstrating that the sensations and movements of the body have much to contribute to intelligent thinking. Mindful attention to the body’s state can calm students’ anxiety, and brisk physical activity can lead students to be more focused and alert.

The discipline of situated cognition, meanwhile, is finding that where we are profoundly affects how we think. Spaces over which students feel ownership increase their feelings of confidence and competence; spaces that are open and flexible promote creativity and collaboration. Lastly, inquiries into distributed cognition are revealing how thinking happens: not inside individual heads, but in concert with other minds. Studies have found that social activities, such as teaching and storytelling, activate beneficial cognitive processes that remain dormant when students do their thinking alone.

Such research has been altering what teachers and librarians are doing in their classrooms and libraries. Though they may not describe their actions in these terms, many librarians are replacing brainbound structures and practices with ones that support students’ extended minds.

As in Tahmaseb’s library, the changes are often apparent as soon as visitors walk through the door. “The Learning Commons, or the ‘no-shh library,’ as we like to call it, is our school’s learning playground,” says Andrea Trudeau, a library information specialist at Shepard Middle School in Deerfield, IL. “We have completely flipped the script and broken the mold of the stereotypical library by creating an active learning environment where staff and students can explore and tinker with new ideas, applications, or instructional technologies with the support of the library staff.”

|

Sensory tiles at the Shepard Middle School library provide physical enagagement. |

At the Learning Commons, “we emphasize teaching the whole child,” says Trudeau. This includes the child below the neck. The library has instituted a “Read ‘n Ride” program that makes exercise pedalers available; students pick up the machines and take them anywhere in the library. “While they read a book, research, or participate in a lesson, they can pedal,” she explains. “It’s a great way for them to get the wiggles out and helps many of our students focus when they have to sit and attend to a task.”

At the circulation desk, students encounter a number of sensory tiles placed on the floor. “Often mistaken for artwork, these tiles are incredibly fun to squish. Students love to watch the colored liquid move and dance,” Trudeau says. The tiles were originally purchased as a way to support students who struggled to wait their turn, she says, “but we’ve found that they also give students a reason to stop by—for a quick squish with their feet and a hello to our staff.”

For visits from classroom groups, Trudeau and her colleagues often set up “stations” where students can freely circulate. Sometimes these stations have a mindfulness theme: One may feature coloring pages with colored pencils and markers; another offers yoga led by a staff member; and a third leads students through breathing exercises, set in virtual reality via an app running on the library’s Oculus Go headsets.

“Even when we don’t have these special stations arranged, we have mindfulness tools at our fingertips each day,” says Trudeau. These include stacking rocks at the library’s Genius Bar (a help desk modeled on the ones found in Apple Stores), calming videos of lava lamps or underwater ocean views shown on the library’s projector screen, and “Lazy 8” breathing diagrams—laminated pages that students can trace with a finger as they take deep, calming breaths.

Space is another “outside the brain” resource in use at Trudeau’s library. When she first joined the library’s staff seven years ago, she did her best to create flexible spaces with the heavy wooden furniture that had dominated the library for more than two decades. A few years later, she was able to engage students in a project-based learning unit on redesigning the space. “Students spent weeks designing their vision of an ideal library. When I met with the architects to determine how we wanted to renovate the space, I brought their sketches with me,” says Trudeau. “It was pretty incredible to welcome students back into the library once it had been completely revamped according to their ideas.”

|

Recess at the Meadowbrook School library |

According to the theory of the extended mind, where we do our thinking affects how well we can think, which means that a smartly designed space can do a lot to enhance students’ learning. Like Trudeau, librarian Tom Bober also oversaw a renovation of his school library at the R.M. Captain Elementary School in Clayton, MO.

Before the redesign, he says, he and teachers often wished that students could engage in informal conversations about their reading or collaborate on a group project, but the design wasn’t conducive to that.

Now, shelves in the library are spaced wide apart, so that students can mingle and talk about books as they browse. “The space has been a game changer,” he says.

The new shelves are shorter, too, Bober notes, “not just so students can reach the books, but so they can have conversations with each other throughout the library.” Tables at standing height, and tall, narrow dry-erase boards encourage small groups of students to gather and exchange views.

Social interaction is another way we extend our minds; according to Clark and Chalmers’s theory: Thinking isn’t conducted inside individual heads, but rather emerges from the connections we make with other people. Promoting collaboration is a priority at Trudeau’s library, which hosts a “Revise-a-Palooza” day for sixth graders working on English language arts projects, and a Shark Tank–style event showcasing student inventions. At Meadowbrook School, “our library is a bustling, collaborative workspace where students come to learn with and from each other,” says Tahmaseb. Students can choose to take part in a traditional, silent study hall or a “collaborative study hall,” in which they study and solve problems together, supervised by a teacher. Tahmaseb oversees the library’s writing center, which is staffed by eighth grade students who have been trained to help classmates and younger students with their writing.

While researching for his book, Tahmaseb interviewed school librarians around the country. “Of course, there are plenty of schools where the old model persists, and for librarians who work in those places, it can be really difficult to break through,” he says. “But in general, those stereotypes are increasingly a thing of the past.”

The philosophers who debate the theory of the extended mind, and the researchers who explore the role of bodies, spaces, and relationships in the thinking process would concur with what Tahmaseb and his colleagues already know: that the active school library is the perfect point of departure for extending students’ minds.

Annie Murphy Paul is the author of The Extended Mind: The Power of Thinking Outside the Brain (HMH).

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!