In Quest for Inclusive Collections, Librarians Struggle To Find Disability Representation

People with disabilities remain underrepresented, or misrepresented, in children’s literature.

Librarians want more children’s books about disability—stories authentically portraying characters living with disability. The problem is finding them.

According to SLJ’s Diverse Books Survey released in October 2018, 62 percent of librarians said that books featuring characters with disabilities were in demand and hard to find; 61 percent said titles with neurodiverse characters—or those with invisible disabilities—were in demand, and 45 percent said those were difficult to find.

|

Becky Standal |

They keep looking, though, because they know representation matters.

Of 1,156 school and public librarians serving children and teens in the United States and Canada, 81 percent said they consider it “very important” to have diverse books in their collections, including titles about disability. That encompasses physical disabilities, such as conditions that require the use of a wheelchair or hearing aid, and “invisible disabilities,” such as autism, ADHD, dyslexia, or bipolar disorder.

“I haven’t found a good way to seek those books out, but I think the review journals have gotten better about making them more visible,” says survey respondent Becky Standal, youth services specialist at Longview (WA) Public Library. She reads professional reviews, then checks other sites for opinions. Reader reviews are good because “people will be really candid about things. There are books that I haven’t bought because they got such bad reviews.”

Finding nuanced reviews is particularly important with titles that could include inaccurate character portrayals. Multiple librarians who responded to the Diverse Books Survey said their source for good books had been the Disability in Kidlit website, which focused on middle grade and YA books. However, the site has gone on indefinite hiatus due to the founders’ schedules; efforts to reach them for comment were unsuccessful.

New Orleans Public Library system youth collection development librarian Kacy Helwick says she refers to reviews and what people with that disability say about the book on Twitter. She and Standal add that they look for books featuring all types of disabilities.

|

Kacy Helwick searches reviews for authentic representation. |

Biggest need in picture books

While more middle grade and YA books featuring characters with disabilities have been published in recent years, the real shortage remains at the younger levels.

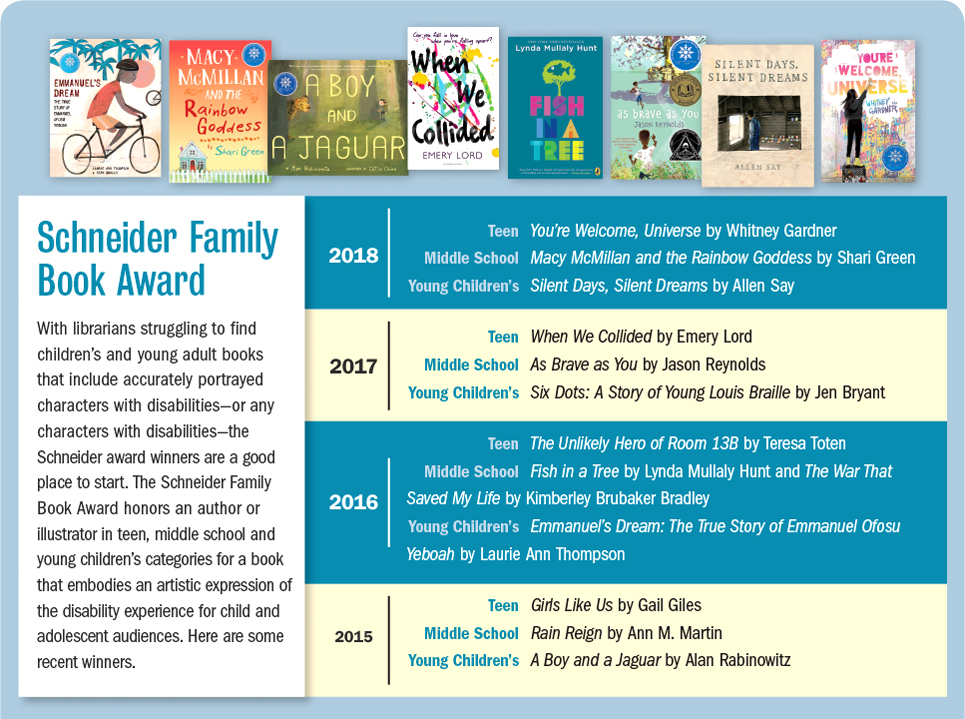

There aren’t enough picture books on disability, says Ed Spicer, chair of the committee for the American Library Association’s (ALA) Schneider Family Book Award, which honors books for children and teens about the disability experience.

“If you imagine the span of a ruler being the total Schneider submissions for picture books and middle grade and YA books, maybe about the first inch is the picture book part of it.”

Standal, who orders about 40 YA books a month for her collection, says she’s seen a lot more titles about mental illness in the last year or two. Teenage patrons ask her for books about anxiety and depression. “They see their own issues reflected in a way that they can relate to,” she says.

But mental illness is a category of its own that seems to have found its place more in the mainstream. Those reviews have been easier to find than ones for books about disabilities.

Helwick, who buys books for the 15 branches in her library system, especially seeks out picture books featuring visible disabilities.

“If you’ve got a picture book and there’s a child in a wheelchair, it’s like, ‘Oh, wow, good.’ You’re looking for visibility so much in children’s books that are so picture-based anyway.” With those books, though, it’s key that the disability is depicted accurately. Sometimes the wheelchair doesn’t look real, or “if you look around in the background, [you ask], ‘How did that person get there? That doesn’t look accessible.’”

Spicer reminds others about the topic whenever possible. “When I walk around the convention center at ALA and walk into a publishing booth, I say, ‘Schneider picture books. Schneider picture books.’” The purpose of the award is to raise awareness, and “if you really want to change attitudes about disabilities, it’s gotta start young.”

He says that Schneider picture book submissions are more likely to be biographies, such as the 2017 winner, Six Dots: A Story of Young Louis Braille, by Jen Bryant, and not a broader range of stories.

“Kids need the whole span of life, including its tougher issues, and the way you change attitudes is by knowledge and exposure, and it’s not being really done very well in the picture book world,” Spicer says.

Ashia Ray, the founder of Books for Littles, agrees. The site, just over a year old, focuses on picture books that address disability rights, gender equality, racial justice, and wealth inequity.

Ray, who has autism, says it’s important to push the issue of children’s books about disability and disability rights in general.

“In terms of bigotry against people with disabilities, we’re where we were with race in the 1920s. It’s very socially acceptable to be ableist. People with disabilities are very much second-class citizens in this country.”

As an example, she cites autism awareness books—warning people about autism as though it should be feared—versus autism acceptance books, which aim for inclusiveness. She sees a higher prevalence of the awareness books.

“‘Oh, watch out, my friend is autistic and look how that kind of ruins your life as a non-autistic person.’”

There is an #OwnVoices issue as well, according to Ray. Many books about disabled people are written by people without disabilities, she says, and focus on disability as something that needs to be fixed.

Beyond autism, Ray says she has found very few books about other invisible disabilities. One exception, she says, is Deaf Culture Fairy Tales by Roz Rosen, though it is aimed at older children.

ResourcesDisability in KidLit is no longer updated, but the website is still an excellent resource that offers reviews of previously published books, interviews with authors, resources, and an "Honor Roll" of titles, so it remains a good place for anyone looking for information. Books for Littles doesn’t focus solely on disability but offers information, including book recommendations. Common Sense Media, an independent, nonprofit organization that provides reviews and ratings of books and media offers, a list of books with characters who have physical disabilities, books with characters who have learning and attention issues, and books with characters who have autism. Each title has a rating and age level from CSM staff, as well reviews and ratings from parent and kid readers. |

In search of authenticity

Despite her clear issues with some published work, Ray does believe there are some picture books that handle disability very well. Hello Goodbye Dog by Maria Gianferrari is “amazing. It’s what I call a normalizing book. It’s got a girl who uses a wheelchair, and she’s not a token. You actually see her use a ramp, you see how that changes the way she moves through the world. But the book’s not about her using a wheelchair, it’s about her dog.”

Why Johnny Doesn’t Flap by Clay Morton and Gail Morton is told from the perspective of an autistic person about his neurotypical friend, noting that his friend has challenges that he doesn’t have. Zetta Elliott’s is “a beautiful book” because it breaks a lot of stereotypes, including racial stereotypes. But books like this are “few and far between,” Ray says.

The Schneider committee wants those books, too. Spicer says, “We’re looking for realistic characters. We’re looking for real people. And we’re looking for real people who have a disability, but the disability doesn’t define them.”

For instance, in last year’s winning teen book, Whitney Gardner’s You’re Welcome, Universe, the deaf protagonist signs a rude retort to a hearing girl who attempts signing to her, out of suspicion of the other girl’s motives. The protagonist isn’t always nice, but she is relatable, Spicer says.

Middle grade and YA appear to have broader representation on disability. Helwick says, “I find that it’s more in the YA books you’re going to find more of the invisible disabilities represented.

“You’re going to find more books [with] a protagonist who’s on the autism spectrum, or where someone’s got bipolar [disorder].” She also notices more titles with characters who have physical disabilities, “like being blind or deaf. I’m finding that more in my YA books, too.”

Ray says books by smaller publishers sometimes address topics that other titles don’t. She tries to help those publishers by telling her subscribers to buy books and donate them to the library.

Spicer, who has served on the Schneider committee for four years, says that winners come from independent as well as mainstream publishers. That includes Toronto-based Pajama Press, which published last year’s middle school winner, Shari Green’s novel-in-verse Macy McMillan and the Rainbow Goddess.

Being an independent, “boutique” publisher can be an advantage with content like this, says Gail Winskill, publisher at Pajama Press. “We can be more selective, and if there is a niche in fiction that interests us, we can focus and develop it quite well.”

Winskill says addressing disability is important to her because both she and her daughter experienced learning disabilities growing up, and she has lived with a recurring physical disability.

In addition to Macy McMillan, Pajama Press, which launched in 2011, offers two chapter books by Sara Leach about a girl with autism, Slug Days and Penguin Days, and Small Things by Mel Tregonning.

Ann Featherstone, senior editor at Pajama Press, says she’s attracted to stories about kids with disabilities, but they have to be about more than the disability. The title character in Macy McMillan, for instance, must overcome more challenges in her life, beyond her deafness.

Featherstone says featuring characters with disabilities helps Pajama Press fulfill its goal of “fostering empathy and kindness.”

That’s the goal for librarians, too. Helwick says, “Every time you read about somebody that’s not like yourself, you learn.”

Marlaina Cockcroft is a freelance writer and editor.

Marlaina Cockcroft is a freelance writer and editor.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!