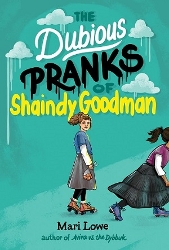

Mari Lowe Pens Powerful Moral Caper for Tweens

A middle school for Orthodox Jewish girls provides the backdrop for The Dubious Pranks of Shaindy Goodman. Twelve-year-old Shaindy tangles with popular girls while participating in a twisted scheme of pranks. Set during the Jewish high holidays, the Bais Yaakov girls learn life lessons about resentment, repentance, and forgiveness.

Mischief disturbs an all-girls school in The Dubious Pranks of Shaindy Goodman

A middle school for Orthodox Jewish girls provides the backdrop for The Dubious Pranks of Shaindy Goodman. Twelve-year-old Shaindy tangles with popular girls while participating in a twisted scheme of pranks.  Set during the Jewish high holidays, the Bais Yaakov girls learn life lessons about resentment, repentance, and forgiveness. Teacher Mari Lowe returns with timeless wisdom after winning a Sidney Taylor Book Award Gold Medal for Aviva vs. the Dybbuk.

Set during the Jewish high holidays, the Bais Yaakov girls learn life lessons about resentment, repentance, and forgiveness. Teacher Mari Lowe returns with timeless wisdom after winning a Sidney Taylor Book Award Gold Medal for Aviva vs. the Dybbuk.

How do sixth-grade girls balance the pressure to be “nice” with the “liquid power” that “flows through their veins?”

These girls are powerful. They understand exactly how to destroy each other in the most brutal ways, and they spend very little time considering long-term consequences. And at the same time, they’re dealing with social, emotional, and physical development that makes every perception skewed and every emotion go haywire. There is such an unregulated desire to be mean that explodes at this age, and it always finds justification. I see girls torment each other all the time, absolutely sure that they’re acting in self-defense.

How do you talk to your students about anger and forgiveness?

Forgiveness is hard. Sometimes we get that sincere apology we’ve been craving, exactly in the way we’ve wanted it. But how often does that really happen? How often can an apology undo the damage caused? Anger is powerful, but it’s also a debilitating emotion to hold onto for a long time. In that sense, forgiveness is about healing yourself more than healing the person who has harmed you. That’s what Shaindy comes to understand in the book.

How do middle school social dynamics impact Shaindy?

Middle school is a rough time! Almost everyone wants to fit in, to be enough like the others around you that you won’t be singled out or isolated.  But at the same time, you yearn for recognition, for someone to look at you and see you as an indispensable friend. Lone wolves get devoured in middle school. Every kid needs a pack.

But at the same time, you yearn for recognition, for someone to look at you and see you as an indispensable friend. Lone wolves get devoured in middle school. Every kid needs a pack.

Shaindy is suffering in school not because she’s being outright bullied but because she’s essentially invisible. And when school is the bulk of her waking hours and her everyday life, that wears away at her psyche until she starts to feel like nothing at all. That moment of connection with another girl—that instant of friendship—is enough to bring her back into visibility.

How would you describe the Bais Yaakov movement?

The movement began in pre-war Europe, spearheaded by a woman named Sarah Schenirer, who fought for girls to get a full-fledged Jewish education. Now, there are thousands of Bais Yaakov schools around the globe. They’re all-girl schools that usually have a dual set of robust Jewish and secular curricula, often taught exclusively by religious women. I attended one for the bulk of my schooling, and I teach at one now.

What does it mean to be a “perfect Bais Yaakov girl?”

I think it’s a universal sort of ideal: the girl who’s good at everything. In my community, that includes a reputation for leadership, for academic excellence, for modesty, for piety, for kindness. I taught a class last year where, when the girls prayed, they’d peek past their prayer books because they each wanted to be the last one to finish and prove their devoutness.

Do you see any differences between your middle school experience and tween girls today?

Social media! It’s almost everywhere, and it’s so debilitating for tweens. Middle schoolers wind up on social media designed for older teens and adults, and they don’t have the experience or the developed prefrontal cortex to deal with it. There’s a permanence and a publicity to mistakes now that makes it impossible to walk them back easily.

Your books may be some readers’ first glimpse of an Orthodox Jewish community. What would you like those readers to discover in your work?

I would love it if they could find the universal stories within the books, and find that commonality with my characters despite our differences in culture. Too much media surrounding my culture tends to be written by outsiders searching for a way to make us seem exotic and alien. I want to write books that are authentically Orthodox, but I also don’t want my culture to be the entire story; rather, a natural setting that will become more familiar to readers.

SPONSORED BY

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!