Move Over, Melvil! Momentum Grows to Eliminate Bias and Racism in the 145-year-old Dewey Decimal System

School and youth librarians update Melvil Dewey's flawed and outdated system.

|

Source photo courtesy of American Embassy School, New Delhi |

All across the globe, book spines carry the same call numbers. Religion? It starts in the 200s. Social sciences? Head over to the 300s. History and geography? Those books are marked in the 900s.

All across the globe, book spines carry the same call numbers. Religion? It starts in the 200s. Social sciences? Head over to the 300s. History and geography? Those books are marked in the 900s.

But a growing number of school and youth librarians are moving to dismantle the Dewey Decimal Classification system—the worldwide cataloging and organizational system for libraries devised by pioneer Melvil Dewey in 1873 and first published in 1876. Not only is the Dewey Decimal System outdated, they say, but many of Dewey’s approaches to categorizing books were racist and sexist. For instance, Black history is not part of American history; “women’s work” is a separate category from jobs; non-Christian religious holidays are situated with mythology and religion; and LGBTQ+ works were once shelved under “perversion” or “neurological disorders” before landing in the “sexual orientation” category.

“After we had done the major renovation of the collection at the library in Doha [Qatar], there was a librarian at the Library of Congress who came to give a workshop. I was cringing that I was going to offend her in some way [for changing Dewey], and she goes, ‘He was a misogynist anyway, good for you,’” says Linda Hoiseth, a Minnesota teacher librarian who works at American international schools abroad. “All those extra decimals were created for someone who was nonwhite male…someone who was considered an other.”

Dewey’s #TimesUp moment has been a long time in the making.

In 2019, the American Library Association (ALA) voted unanimously to strip Dewey’s name from its top honor, citing a history of racism, anti-Semitism, and sexual harassment. “Whereas Melvil Dewey did not permit Jewish people, African Americans, or other minorities admittance to the resort owned by Dewey and his wife,” reads the resolution approved by ALA.

“Whereas the behavior demonstrated for decades by Dewey does not represent the stated fundamental values of ALA in equity, diversity, and inclusion,” the statement continues after listing several other Dewey offenses.

The move came more than a century after Dewey had been ostracized by ALA, the organization he helped found, for sexually harassing four female members.

|

The Traditional Tales collection at the

|

The push to slowly shift away from some of Dewey’s overtly biased categorizations comes amid a greater effort to decolonize—or build racially equitable—libraries in general. Simply put, it’s an attempt to be more inclusive of voices of color, to highlight diverse perspectives, and to decenter whiteness, wrote Nicole A. Cooke, an associate professor at the University of South Carolina, in an op-ed in Publishers Weekly last year. It’s not easy and it can’t be done all at once, librarians say. Rather, it’s a thoughtful, continuous process.

And as with decolonization, many school librarians are dismantling Dewey one section at a time with a threefold goal: Eliminate the bias, create more inclusion, and make cataloging more accessible to students to help increase circulation.

“We are trying to make it more intuitive for students so they can browse better and they can find relatable things they might not have found otherwise,” says Hoiseth. “My personal motto is: If I can’t put a label on a shelf that will tell the students what’s on that shelf, then it’s not organized very well.”

So where to start?

Challenging the status quo

Over a decade ago, Jess deCourcy Hinds, a library director at Bard High School Early College Queens in New York, made some small tweaks, such as alphabetizing plays and poetry, just like works of fiction.

“I was a Dewey rebel from the beginning, but in a very restrained way,” she says, laughing. “People have described the Dewey Decimal System as a house of cards, where if you pull out a few cards here and there, a few cards will topple over. I didn’t want to make changes hastily.”

More recently, Hinds knew it was time for the Dewey system to undergo more scrutiny. However, she wanted to take the lead from her students who were inclined to tackle some of the more obvious injustices.

While doing research with three student library interns, Hinds learned that years ago, Howard University librarian Dorothy Porter flagged that all books by Black authors—no matter what topic—were in 325 (for international migration and colonization). And it seemed that the mainstream hadn’t really corrected that since then.

“It’s hard to erase the history of these structures,” Hinds says.

Still, her students set about to reclassify the books that dealt with Black history.

“I wanted to take a closer look at why immigrants and African American history were separated from American history, and that was when we [Hinds and her students] got angry,” she says.

For example, Hinds and her students questioned why speeches by President Obama landed in two different sections (civil rights/social science or American history). Ultimately, she decided to group all his works under American history.

Not all books by Black authors were moved, though. Cornel West, for example, remained in the 300s because his books examine race—a seamless integration in the social science category.

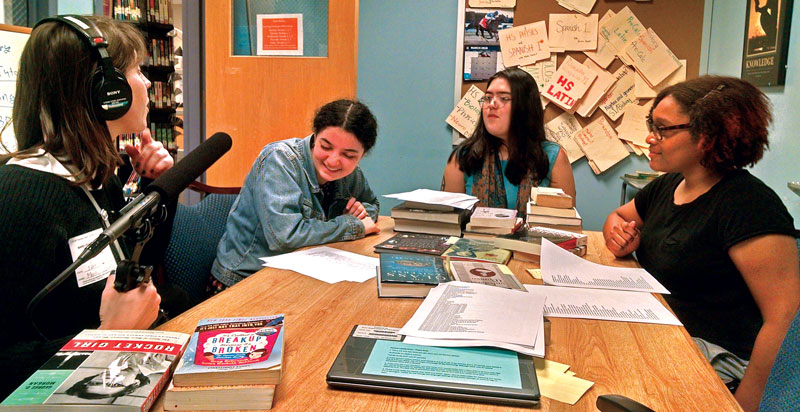

Hinds and the student interns, who were asked to present their project at the Association of College & Research Librarians conference at Baruch College in 2018, took a similar approach with other underrepresented groups. They created their own numbers in the 973 section by ethnicity.

“Students didn’t want people of color to be pigeonholed. They wanted them to be in American history. But they still wanted the history of Asian Americans to be in its own cohesive [spot],” she says.

In some areas, though, she abandoned the numerical classification and used call letters instead.

“I had students who wanted to create an LGBTQ section, and so we just used the call number LGBTQ; and then FIC or NONFIC or GN for graphic novel, and so we put that section up in the front as well with other creative works,” says Hinds.

When creating a bilingual language section, she decided to group those books near Spanish, Chinese, and Russian books. She added a shelf with BIL-SPN for bilingual Spanish, BIL-CHI for bilingual Chinese, and BIL-Rus for Russian.

“I’m steering people towards thinking about things in a way that values our community,” she says. “Creating a library with social justice [objectives] isn’t just the labeling, but it’s the display and the promotion.”

|

Molly Schwartz, then with the Metropolitan New York Library Council, interviewed students from Bard HSEC Queens. The show later aired on NPR. Photo courtesy of Jess deCourcy Hinds |

Making an inclusive space

The treatment of religious holidays just did not sit right with Leslie Howard, a librarian at Fairhill Elementary School in Fairfax, VA. Thanksgiving, Christmas, and Easter were in the typical holiday section with a 390 distinction. But books about Eid, Rosh Hashanah, Diwali, and other non-Christian holidays were in mythology and religion under the 290s. Howard says she realized “how wrong this was” after giving it some serious thought. Her district had already been discussing issues around equity and access and building relationships with students and their communities, and this restructuring was an extension of that.

Howard’s school has a diverse population, and she wants every student in the building who celebrates a religious holiday to find books about all of them in the same place. The pandemic gave her the flexibility to devote time to the project this year, since the district allowed her to tackle tasks not related to student achievement. She created a special collection and pulled all the books from their Dewey categorization and made one holiday shelf for them.

“It just makes good common sense to me,” Howard says. “If you want your library to be representative of your student population, this is a very simple solution.”

Next, Howard is hoping to tackle that “women’s work” distinction.

“Cookbooks and babysitting, why is that separate from careers and jobs? It’s odd,” she says. “I respect what [Dewey] attempted to do all those years ago and his frame of mind. He created this system before we had space exploration, but we found ways to make that fit in. I’m sure there are ways to adapt and adjust, make it fit our world.”

No one-size-fits-all approach

Hoiseth spent about two years, on and off, reclassifying sections in the library at the American Embassy School of New Delhi. She took on a similar project when she worked at the American School of Doha. And now, as she heads to the American School of Dubai, she expects ditching parts of Dewey to occur organically.

“It really becomes collection specific. The way I reorganized in Doha was different than the way I reorganized in Delhi because of the units that my students studied and because of what had already been collected,” she says. “The decolonizing part is just a bonus.”

For instance, Hoiseth says she was frustrated that British and African poets were in different places and that men and women had different decimals. Since the majority of poetry was classified under 811, she moved it all there. When it came to decolonizing the history section, she took the chronological approach to the 900s. That’s how students were looking for research materials anyway, she says.

“We left the biggest collections where they were. So, the World War II collections stayed in place, and then we arranged the others to work around it,” she explains. “I’m not above making up numbers. We just made up numbers to make them fit on the shelf where we wanted them to fit.”

Creating an inclusive environment was also important to her. Since a large portion of her students in New Delhi were Indian American or of East Asian descent, she created an entire room devoted to Indian nonfiction and fiction.

“We named [the room] after an Indian poet, and we decorated it, and we really wanted to highlight the collection,” says Hoiseth. “When I got there, [the Indian collection] was kind of shoved in a corner and ignored.”

“It’s really about accessibility,” Hoiseth adds. “It’s not about following a system.”

Getting books into students’ hands

When Denise von Minden, a teacher librarian at Flagstaff Academy, a K–8 charter school in Longmont, CO, was tasked with genrefying her library five years ago, she decided to break it into three sections. There was a nonfiction section with 20 genres; fiction with early reading and middle grade chapter books; and the picture book section. And for each of those sections, she created subheadings.

“My focus was very much more on getting the books into the students’ hands. Making it as much of an easy shopping experience for them versus anything else,” says von Minden. “These kids have grown up with the bookstore model, being able to walk into any store and grab exactly what they want. Having to work too hard for it using Dewey wasn’t going to work.”

Over the years, she’s continued to tweak the system. The way she classifies books must be fluid and ever changing. For example, she realized that 20 nonfiction genres were too many. Some genre names just weren’t drawing students in.

“Our kids are changing all the time,” she says. “What we know about our kids and what we know about books that are coming out. It changes constantly.”

And while von Minden believes the system helped eliminate some of Dewey’s inherent biases, she recognizes there’s more work to be done on her end. On one hand, she wants students to find books that interest them more easily. But by placing groups of picture books featuring Black history stories together, was she “othering”?

She’s also challenging herself when it comes to the integration of more queer lit into the collection. She wants to make sure she’s thoughtfully cataloguing the books, not just lumping them together because it’s convenient.

“All of those debates happen constantly within the library and my own brain,” says von Minden. “Especially [since I am] a white librarian and in a fairly white school. It’s easy for me to sit on what we have and let it go, but I have to be better than that—and I have to stay on top of what the thinking is, and the learning is, and do better for my kiddos.”

Christina Joseph is an editor, writer, content strategist, and adjunct professor with expertise in race relations, immigration, education, health care, and government.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!