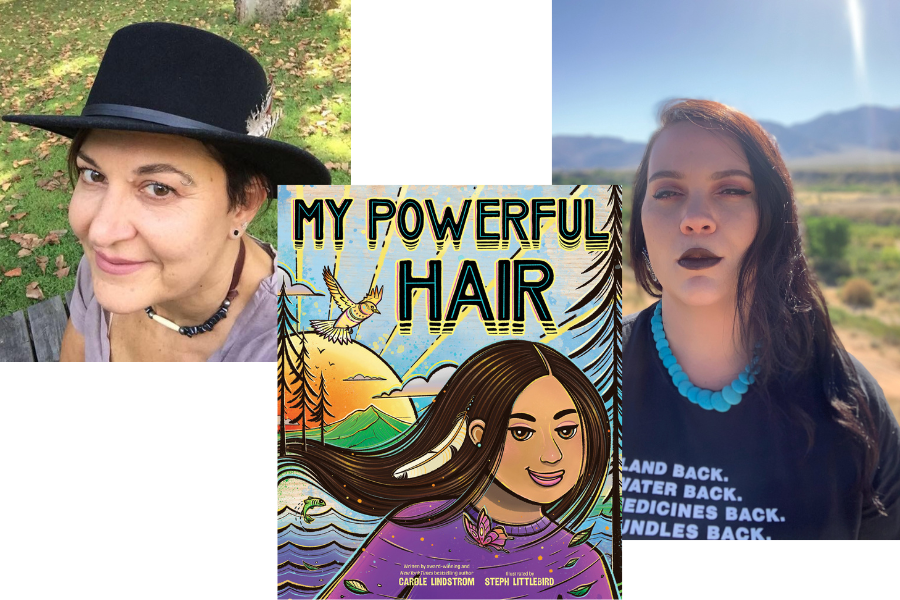

Carole Lindstrom Turns Family History into a Song of Hope

By reaching back two generations to the abuses suffered by her grandmother in boarding school, Carole Lindstrom, author of the Caldecott Medal-winning 'We Are Water Protectors' reclaims a piece of Indigenous culture about the power and beauty of long hair.

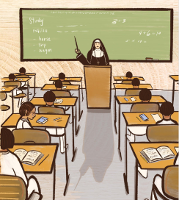

At boarding schools in the early 1900s, Indigenous children were kept from their parents and families, against the will of their families, and only returned during the summer.

Worse, as Carole Lindstrom writes in the author's note of My Powerful Hair, "Some children never made it back to their families. Many died in the boarding schools from disease and abuse. Their languages, ceremonies, and cultures were stripped from them. The motto of the Indian boarding schools was “Kill the Indian, save the man.” When children finally returned to their families after years in the boarding school, they didn’t know their Indigenous languages any longer. Didn’t know their ceremonies. Didn’t know their culture. It was all intended to die in those boarding schools. And it did die. I understand that, to my grandmother, long hair was taught to be a sign of 'wildness' and 'savageness.'"

In fact, so ingrained were these ideas that Lindstrom’s grandmother, long after she left boarding school, kept her own daughter’s—this is Lindstrom's mother—hair short. The shame of long hair thus became generational.

Carole Lindstrom, author of We Are Water Protectors, which won the Caldecott Medal, is a registered member of the Turtle Mountain Band of Ojibwe, while illustrator Steph Littlebird, making a debut here, is a registered member of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde, Oregon. By reaching back two generations to the abuses suffered by her grandmother, Lindstrom and Littlebird reclaim a piece of Indigenous culture about the power and beauty of long hair in My Powerful Hair.

SLJ: Carole, the text is so spare, almost a poem. How ever did you decide what to include and what to leave out?

SLJ: Carole, the text is so spare, almost a poem. How ever did you decide what to include and what to leave out?

Carole Lindstrom: Picture books, by their nature, are very short books—usually less than 500 words. The less the better. With that in mind, I am very particular about every word I choose. Each word, I think about whether it is needed to further the story along. I also have to be very cognizant of the illustrator and leaving plenty of room for the illustrator to interpret the words into visuals for the reader. If the illustrator can convey with their art then I know that the text won’t be necessary.

SLJ: Carole, a follow-up question. The mood of the book is mostly bright, and fairly serene, despite phrases such as “hers was taken,” about the cutting of hair, and even when the elder dies—when the narrator’s decision to cut her own hair is placed in an understandable, accepted cultural context. The author’s note that follows is dark, covering very cruel truths. This is a real split. Can you talk about that delineation?

CL: Children are very smart and have an innate sense of fairness and equality for all that some adults lack. Because they haven’t been tainted or jaded by the world they’re very pure of heart and mind. The author’s note is meant to tell the truth to the reader, because picture books are typically read to children by adults, it’s important that adults have some context of the book and the realities of life for Native Americans. Adults need to be told these truths, even if they may seem ‘cruel’ or ‘dark.’ These were and are the truths for most Native families and it’s very important that these truths be known to not just the young readers, but the older readers as well. Many times I’ve come to find our children are the best teachers. We must listen to them.

SLJ: Carole, how long did it take you to write this book, from first seed to full manuscript?

CL: I’m never good with this question…HA. Sometimes seeds stay in my mind for many years before I feel like I have enough soil and water to make them a full grown story. This manuscript probably took about six months once I started working on it and then refining it.

[Read: Review of We Are Water Protectors by Carole Lindstrom, illustrated by Michaela Goade]

SLJ: Steph, what was your research like? Where did you begin?

Steph Littlebird: This was my first children's book, so I spent a lot of time studying the format of picture books to understand what it takes to make a successful story. My biggest challenge was getting the ages of the characters correct. Illustrating children of different age groups is very nuanced and as an Autistic person, I have always struggled with interpreting emotions/social cues, so this was an opportunity to really learn and improve that skillset both professionally and personally.

SLJ: Steph, at first glance the illustrations look like woodcuts, perhaps enhanced digitally. Then I read the copyright page, sketches in pencil to Procreate (digital). What were your decisions or thinking before choosing this direction, or style?

SL: When I went to art school, I spent most of my time between the painters studio and the print studio. Woodcut printmaking is one of my favorite mediums to work in because it's so tactile and accessible. I incorporated those aesthetics for young readers because I wanted to make the book feel textured. I worked with Abrams to refine this approach as we went through the sketch process, because at first my linework was too "clean" (this is where my design influence comes in). Using rough textures and watercolor brushes in Procreate helped me achieve a more layered end result.

SLJ: We are enamored of the symbols on the title page: the hat of the elder, or the grandfather, and the basket. What was the thinking behind this choice? Are these symbols for you, Steph, or for Carole?

SL: I was thinking about the words in the story: our hair connects us to our memories and our ancestors. The hat represents Grandpa, who eventually walks on to become an ancestor, and the basket is a reference to the memories the main character makes with her grandpa throughout the book. It's a nod to the cycle of life and how our memories connect us to previous experiences and loved ones.

SLJ: For both of you—did you collaborate or go back and forth at all? For most picture books, there is the text and then the art. Is that the way here?

CL: Yes, we definitely collaborated. You are correct that typically the text and the art are kept separate. That is mostly so the author doesn’t influence the illustrator. But in this case, since the story is specific to a tribal nation, it was important that Steph and I speak so that I could share cultural links and resources.

SL: Carole had already written the poetic words for the book and it was my challenge to illustrate them in a way that honored her important story. The process started with basic sketches of my ideas and over many rounds of feedback from both Carole and the publisher, those eventually got refined. The last step is adding color which is where things really come to life (that's my favorite part!).

SLJ: For Carole: what are the complications or the glories of telling personal stories? Is it easier or harder?

SLJ: For Carole: what are the complications or the glories of telling personal stories? Is it easier or harder?

CL: It’s harder, for sure. Living these stories as I bring them to life can be very hard on my psyche. I feel a lot of pain, hurt, shame, sorrow, love for my people, pride for my people, anger, hurt—lots of emotions. I really find seeing a therapist helps me to come to terms with these feelings. But I do know no matter how painful they are for us, they MUST be told.

SLJ: For both of you—what are you working on now?

CL: I’m working on a middle grade historical fiction novel, a graphic novel, and a few picture books. I like to have a lot of irons in the fire.

SL: Aside from my job as an illustrator, I am also a curator and just opened a new exhibition, "This IS Kalapuyan Land," about Oregon's own Indian Boarding School. The work I did with Carole directly ties into what I do as an Indigenous curator and writer. Much of my work revolves around serving the Native community and making visible those histories which have been erased and forgotten.

SLJ: Carole, the narrator seems to heal her mother—they are both growing their hair out. It feels hopeful, anyway. Is this from your own life?

CL: Yes. It’s based on my grandmother and my two great aunts being sent to boarding school. My mom had a picture of the three of them with their dark hair chopped short and it always haunted me. When I was young, I didn’t understand the Indian boarding schools and the horror they were intended to create in our lives. Neither did my mom or grandma. They just lived it. It’s only now that I’m older that I am understanding and dealing with the trauma these boarding schools created in my life and thousands of other Native families.

[Read: Native Perspectives: Books by, for, and about Indigenous People | Great Books]

SLJ: For both of you—what would you like children to feel or know as they finish this book? If they have questions about how we grieve, or anything else, can you recommend resources?

CL: I would like children to understand how important our hair is to our culture. I’ve seen instances in the news about Native boys getting their braids cut by teachers or other students in schools. I want all children, and adults, to understand our hair is an extension of us. Our hair is our power and our strength. It’s like a scrapbook of our memories and all the people and places we’ve touched and that have touched us. Hair is a celebration of our culture.

CL: I would like children to understand how important our hair is to our culture. I’ve seen instances in the news about Native boys getting their braids cut by teachers or other students in schools. I want all children, and adults, to understand our hair is an extension of us. Our hair is our power and our strength. It’s like a scrapbook of our memories and all the people and places we’ve touched and that have touched us. Hair is a celebration of our culture.

I hope this book is seen as more than a book to help with grief. It does show a sad scene where the main character buries her hair with her grandfather, but that is meant to be a symbol of love, to give a piece of herself that is so very precious to her. That shows her love for him and that she wants him to have a good journey to the spirit world. That is all very beautiful and healing for Native peoples. I believe that young readers will also see and appreciate the beauty in giving away something so important and so personal to them. That is a most selfless act and young people will understand that act. Also, the book ends on an uplifting note where the main character and her mom will be growing their hair out together. This speaks of the healing that is taking place within her mom to be able to grow her hair out now. And that she is doing it with her daughter. It’s a very healing and powerful moment.

SL: We want Native kids to feel seen by this story. As a young Native kid, I was starved for representation that looked like me. There were no books like this when I was a child, so ultimately I want them to feel validated and see their cultural values represented positively. Much of Indigenous culture is also seen as being "in the past" but in fact, Native people are still here. So it's important for people of all backgrounds to see contemporary Natives and understand the importance of hair in Indigenous culture.

This story is also coming out at a pivotal time for Indigenous people of the US. The legislation known as ICWA (the Indian Child Welfare Act) is likely to be overturned by the Supreme Court this June. This legislation was created as a direct response to the boarding school system in America and the painful "scoop" era of the 1960s and '70s when Native children were taken from their communities and given to non-Native families. If this law is in fact overturned, Indigenous communities are concerned about what will happen to their children if these protections are taken away.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!