The Candle and the Flame: Finding the Power of Story

Stories give us a place in which to locate our shared histories; stories are an affirmation of our selves. Stories of the past give birth to the narratives of today. Stories of the present allow dreams of the future. The stories I read gave me the courage to write my own tale.

The first fairy tales I heard were breathed to life by the quivery voice of a great aunt who looked after me while my parents were at work. The princesses in the stories she told always lost their hearts, their loves, and in short order, their lives, and were buried, often, at the back of their houses in unmarked graves. I remember staring wide-eyed at my great aunt, my mouth gaping, and my mind racing with images of these princesses who, according to their descriptions, could be my older sisters. They lived such fantastic lives, went on adventures, loved, and died refusing to submit. They were the magic I wished to be.

The first fairy tales I heard were breathed to life by the quivery voice of a great aunt who looked after me while my parents were at work. The princesses in the stories she told always lost their hearts, their loves, and in short order, their lives, and were buried, often, at the back of their houses in unmarked graves. I remember staring wide-eyed at my great aunt, my mouth gaping, and my mind racing with images of these princesses who, according to their descriptions, could be my older sisters. They lived such fantastic lives, went on adventures, loved, and died refusing to submit. They were the magic I wished to be.

I grew up in a small village called Vitogo which is located on Viti Levu, the largest island in Fiji, a country made up of islands. Western fairy tales such as Cinderella or Rapunzel with their blonde princesses didn’t interest me because the lives they led and the adventures they had felt so alien to me. I was in search of a fairy tale I, and girls like me, girls drunk on sugarcane juice and the sun, could find a home in.

Books in Fiji are hideously expensive. As a kid with very little spending money, I had to get creative with my methods to gain reading materials. There is one public library in the city of Lautoka where I went to school. Their offerings in my time were…bleak, to say the least. When I was ten, I had read everything I wanted to read in the children’s section. When I tried to take out a book designated “Adult,” the librarian kindly told me that I needed my dad’s signature to turn my library card into one that could take out any book my heart desired to. You have to understand that we lived in village seven kilometres away from the city and I wasn’t willing to go home, get the signature, and come back. I was desperate. So, I forged my dad’s signature, fooled the librarian, and got to check out the books I wanted to. It was a small victory but one that I, nevertheless, savoured.

The library only allowed us to check out two books at a time and this was in no way enough for us. My cousins and I would save the thirty cents we would each get as allowance every day and every Friday we would sneak away from the bus station and follow the path between the vegetable and fish markets to the back of the town where giant mango trees grew. Beside these trees, in a shabby complex, was a thrift store that was more precious than candy stores to us. This store got its stock from Australia and often had used books on sale. There were two barrels full of old books in varying conditions. We spent carefully timed half-hours searching for books in there. Sometimes we got lucky; sometimes we went back emptyhanded. I once found a copy of Anne of Green Gables with no front cover. Something about it appealed to me so I read it. Though she was no princess, (through no lack of effort on her part), Anne’s adventures led me to the same place as my great aunt’s stories; my imagination was newly set ablaze. I became even more determined to find a story that I could belong in.

In Fiji, students who come first, second, or third in their class get a book prize at the end of the year. This was a somewhat extreme way to get books but I was desperate. After we moved to Canada, finding books became a lot easier but to my surprise, finding myself in stories became even more difficult. No matter the genre, people who looked like me or had names that sounded like mine were either completely missing from the narratives, were soon dead best friends, or were antagonists that met tragic ends. Still, the libraries here in Canada have a fifty-book limit and I refused to believe that I wouldn’t be able to find a book that gave me the reflection I was so thirsty for.

It took a long while but I finally came across Alif the Unseen by G. Willow Wilson. I was blown away by the entire book but especially by Dina, a female character who wears the hijab. It was the first time I had come across someone who looked like me, lived in a culture similar to mine, in a speculative novel. The experience was electrifying. As weird as it may sound, at that moment, I felt seen. I felt acknowledged. Reading Dina gave my stories weight and my voice depth. I felt that I existed beyond the boundaries of my mind.

Stories give us a place in which to locate our shared histories; stories are an affirmation of our selves. Stories of the past give birth to the narratives of today. Stories of the present allow dreams of the future.

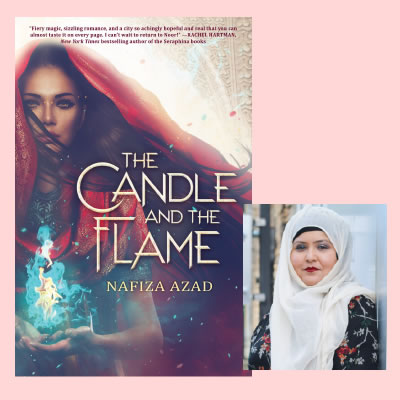

The stories I read gave me the courage to write my own tale. The Candle and the Flame was a response to my own quest to find someone like me in a fantasy novel, having adventures and being magical. The Candle and the Flame is about Fatima, a human girl who lives in a city ruled by both humans and the Ifrit clan of Djinn. When her mentor, an Ifrit called Firdaus, is killed in front of her, her world is irrevocably changed. She discovers that she has Djinn fire, a Name, and a power essential to Djinns. This places her in a war simmering beneath the surface, a war that could destroy the people she loves and the city she calls home.

I was a little girl who lived on a small island in the South Pacific. The books I read and the stories within them gave me multiple names, multiple selves, and a range of experiences. Perhaps someday someone will find an old battered copy of The Candle and the Flame just like I found my coverless copy of Anne of Green Gables. Perhaps they, too, will read the story within with eyes racing across the pages and breaths bated. Perhaps their imaginations, too, will be set ablaze, just like mine was. Just like mine still is.

Nafiza Azad was born in Fiji and spent the first seventeen years of her life as a self-styled Pacific Islander. Now she identifies as an Indo-Fijian Muslim Canadian, which means she is often navigating multiple identities. Nafiza has a love for languages and currently speaks four. She holds a Master of Arts degree in Children's Literature from the University of British Columbia and co-runs The Book Wars (thebookwars.ca), a website dedicated to all things children's literature. Nafiza currently lives in British Columbia with her family.

This article is part of the Scholastic Power of Story series. Scholastic’s Power of Story highlights diverse books for all readers. Find out more and download the catalog at Scholastic.com/PowerofStory. Visit School Library Journal to discover new Power of Story articles from guest authors, including Lamar Giles, Andrea Davis Pinkney, book giveaways and more.

SPONSORED BY

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!