Solace Through Story: Books about school shootings encourage conversation

Middle grade and YA authors tackle the unfathomable and the long reach of tragic events.

|

Illustration and SLJ May 2025 Cover (below) by Dion MBD |

Teachers, staff, and students: Code RED. Adults, procedures must be followed.

—The Making of Yolanda la Bruja by Lorraine Avila

The voice over the loudspeaker in Lorraine Avila’s 2023 YA novel sets a familiar scene in this country—a school going into lockdown with an active shooter on campus. Schools do their best to prepare for and prevent these incidents with training, drills, and increased safety standards, yet school shootings continue to happen.

Gun violence is the leading cause of death for American children ages 1 to 17. According to the Switzerland-based independent research project the Small Arms Survey, there are 120 guns for every 100 Americans, making America the only nation in the world where civilian guns outnumber people. Fifty-eight percent of adults in America favor stricter gun control laws. But without those laws, children and caregivers must learn not only how to protect themselves from gun violence, but also how to live with resilience and bravery in a society where guns are so prevalent.

That’s where books can help. Middle grade and YA authors are stepping in, taking close looks at how these shootings affect survivors, friends, teachers, siblings, and parents. The stories—which show the personal and community impacts, how survivors move forward, and how young people process the violence—can encourage conversations, understanding, and maybe even action.

Authors have a variety of reasons for building stories—fiction and nonfiction—around gun violence. Some are deeply personal.

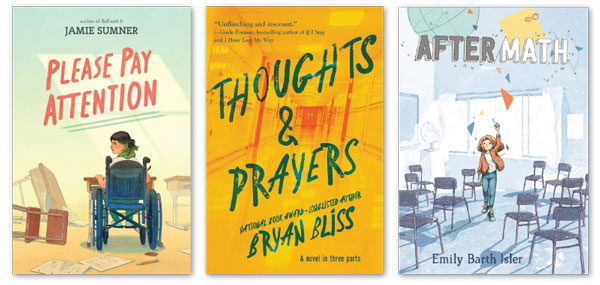

“On March 27, 2023, I lost a close friend in the school shooting at the Covenant School in Nashville. As a former teacher, I had worked with Dr. Katherine Koonce. I also taught her daughter,” says Jamie Sumner, author of the middle grade novel Please Pay Attention (Atheneum Books for Young Readers, April 2025), which is dedicated to Koonce. It’s about a young girl, Bea, who survives a school shooting. Bea has cerebral palsy and uses a wheelchair; her experience during the shooting is complicated by the fact that she cannot quickly get to safety the way her classmates can.

Episcopal priest Bryan Bliss felt “devastated and deeply angry” after the 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting in Newtown, CT, in which 26 people, including 20 first graders, were killed.

“At that point I realized—perhaps embarrassingly late—that the legislators and gun advocates simply didn’t care,” he says.

Having always relied on writing to help him process events and feelings, he wrote Thoughts & Prayers (Greenwillow, 2020) to try to find answers about gun violence.

“If the laws of our country aren’t going to address it, then art and literature have to,” he says.

Thoughts & Prayers follows three teens in the wake of a fictional school shooting in North Carolina. At one point, Eleanor—one of the students, who becomes the face of the local gun control movement and “Liberal Enemy #1”—thinks adults “care more about guns than they do about me.”

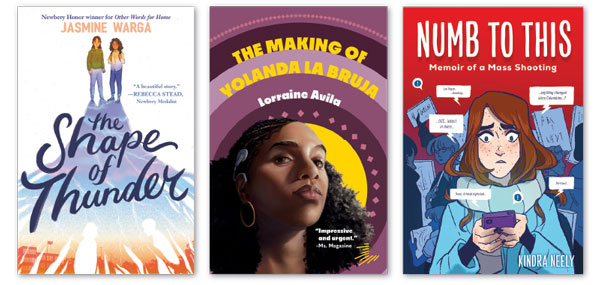

Jasmine Warga wrote the middle grade novel The Shape of Thunder (HarperCollins, 2021) about two friends—the sister of a school shooting victim and the sister of the shooter—trying to repair their friendship in the face of grief, guilt, and regret. Warga was inspired to write the book after being “startled, as a parent, by how young conversations about gun violence have to start now because of school drills.” According to Everytown for Gun Safety, the largest gun violence prevention organization in the United States, 95 percent of public schools hold drills on lockdown procedures.

“Books, for me, have always been the best way to broker difficult conversations,” says Warga.

Avila spent over a decade in the classroom teaching elementary and middle school students.

“Drills and the doom of the possibility of a school shooting took up a large amount of my brain space,” they say.

Their experience witnessing the courage and fears of former students helped inspire The Making of Yolanda la Bruja (Levine Querido, 2023), in which Yolanda Alvarez, a burgeoning bruja, has disturbing visions of Ben—a white male student with a history of racist harassment who is new to her Bronx school—threatening violence. Lonely, angry, and bitter, Ben speaks derisively about “social justice warriors” and believes “we have to take back our country.” Yolanda is one of his targets when he does indeed open fire in their school.

Avila was moved by their students wanting to engage in conversations about the issue and address their concerns.

“Witnessing the courage of many of my former students to stand up for themselves and use their fears as fuel inspired me greatly,” Avila says. “I hoped the topics explored in this story could help marginalized students remember that their fears aren’t wrong.”

After researching school shootings, the author noted that “most assailants were white boys reacting to rejection, [who] had exhibited racist, xenophobic, and homophobic behaviors.” Because of this, Avila hopes that white educators who engage with the novel can connect with white students to explore how this climate of violence affects them and how they can rise above it. “It is crucial that all students have the guidance to alter the extreme realities of violence we are experiencing,” Avila says.

Emily Barth Isler took on the subject of gun violence in AfterMath (Lerner/ Carolrhoda, 2021), about a middle schooler who moves to a community where all of her new peers survived a school shooting as third graders. It was Isler’s way of continuing the work of her grandfather, Washington Post journalist Alan Barth, who wrote many editorials in the 1960s calling for gun reform. While she hopes her novel “plants seeds of empathy” for survivors and facilitates meaningful conversations, she also wrote the book as a parent with small children.

“Many people have asked me if I’m a survivor of gun violence myself,” she says, “and I’m lucky that I’m not, but I am a mother in America—a human being in America—and I think we are all affected on some level by the constant threat and the constant reality of this kind of violence.”

Isler says it’s never too early to start talking about this big issue: one of her children had active shooter drills at her Jewish preschool.

Kindra Neely is a survivor of gun violence. Their graphic memoir, Numb to This: Memoir of a Mass Shooting (Little, Brown, 2022), recounts their experience during the 2015 Umpqua Community College shooting near Roseburg, OR.

When asked what that experience was like, Neely says, “I never know how to answer this question—how do you speak about things that are unspeakable?” Neely recalls the confusion, panic, and sick feeling they experienced while running and hiding. And, when the incident was over, life had changed: Neely remembers “getting home, looking in the mirror, and realizing there was something within me that would never be the same.”

Their memoir details those lasting effects—the hatred of small or crowded spaces, the need to clock exits, the dislike of loud noises, as well as the continual flashbacks and triggers—and asks how we can get better, as a country, when we argue so much over gun violence.

These books don’t provide all the answers or neatly resolve all the issues. For Warga, writing is more about asking questions. Her main characters in The Shape of Thunderwonder about why they feel guilt, how they can repair the rift between them, and whether it’s possible to find a wormhole and change the entire course of events.

“This is a book that asks questions—it’s not a book that gives answers—and that’s very intentional,” says Warga. After all, in reality, there are no satisfactory explanations for why shootings happen or what drives people to commit such horrific acts.

Sumner, who sees her book as a call to action, asks specific logistical questions in her novel, informed by real life.

“My son is in a wheelchair and uses a speaking device to communicate,” she says. “Who would help him seek cover in a school shooting? Who would explain to him what is happening?” These are vital questions for which every school should have ready answers—and yet “these are not thoughts any parent or teacher should need to have.”

Neely has a unique perspective as both an author/illustrator and a survivor. After the 2015 shooting at Umpqua, Neely sought out material about similar experiences.

“I desperately wanted something to connect to,” they say, “and hoped I would find answers about what my life would look like as I continued my education.” But they didn’t find much that was useful. Few books written by gun violence survivors are available for tweens and teens.

Knowing books offer safe spaces to think through experiences and process emotions, Neely wanted to provide that opportunity for others. “I thought teens dealing with similar experiences could have a small space on their shelves where they felt safe and seen.”

Readers of Neely’s memoir will get a much better understanding of how a shooting can affect a survivor. For Neely, the PTSD is still present, though it has lessened over the years with work. But reminders of that event are everywhere. “It can still be very difficult to capture and hold on to the light of hope when there are so many more mass shootings happening—and very little progress being made to end them,” Neely says.

Readers of Neely’s memoir will get a much better understanding of how a shooting can affect a survivor. For Neely, the PTSD is still present, though it has lessened over the years with work. But reminders of that event are everywhere. “It can still be very difficult to capture and hold on to the light of hope when there are so many more mass shootings happening—and very little progress being made to end them,” Neely says.

Working on their memoir was “deeply healing,” Neely says, though “healing is not always a beautiful or calm experience.” They felt different emotions while revisiting the past, often feeling like a child taking medicine. “I knew it would ultimately make me feel better, but the thought of the bitter taste was enough to make my eyes water.”

While Neely’s book comes from firsthand experience, the other authors drew on research. Bliss spoke with adolescent trauma experts, focusing not on the actual moment of a shooting but instead about “what happens when the trucks leave—when the next tragedy occurs and whips up the news cycle once again,” he says. “It was important for me to get the anxiety, the fear, and the grieving correct.”

As a teacher, Sumner had taken part in active shooter drills, “but to fact-check my own accuracy, I partnered with the Young Editor’s Project to find student readers to offer honest feedback. They all commented how routine these drills had become. They are as mundane as tornado and fire drills.”

As Warga worked on her book, she spoke to educators to learn more about “the fear and anxiety they and their students experience.” She knew these personal stories would help elucidate the worry she was portraying in her book and could “provide a framework to talk through the stress and fear that many kids may be carrying.”

Isler worked on being particularly mindful not to glorify or justify a shooter’s actions in her novel. “I learned that absolutely anything in a narrative that attempts to justify, explain, examine, and/or understand a perpetrator’s possible ‘motive’ for a school shooting is not productive or helpful,” she says. Isler, who consulted with multiple gun violence prevention advocacy organizations while writing, goes on to say, “To write about a perpetrator’s motive is to humanize and sympathize with them, and that is not the message we wish to spread.”

Whether aimed at middle school students or high schoolers, these books reassure readers that adults are indeed worried about gun violence. The books also show that it’s OK to not always be strong, hopeful, or resilient—sometimes, everyone is scared, angry, and disgusted.

Having written about gun violence, many of the authors also use activism to focus on the issue. Bliss has done a lot of work in prisons. “While it’s not gun violence,” he says, “the connections are obviously and unfortunately pretty close. We have a problem in this country, and there’s almost no aspect of our culture that is left unscathed.”

Avila feels their “presence in the classroom, supporting students, has been my activism.” Isler has donated a large portion of the profits from her book sales to gun violence prevention organizations, is an active member of Moms Demand Action for Gun Sense in America, is on Everytown’s Authors Council, and works on fundraisers.

Sumner says activism comes in many forms, large and small, and there are things we all can do, just as her main character seeks change by writing a letter to a state leader urging the passage of laws making it harder to get guns. She encourages readers to advocate in whatever way they can. “If you want to march, then march; if you want to make phone calls to the governor or start a petition at your school, do that. Just don’t give up.”

Children can’t be shielded from hard, upsetting things. Even if they could—and plenty try—it does them a great disservice. Real life is going to happen whether they read about it or not. Warga has worried that her book’s painful subject matter means it isn’t often promoted to young readers by librarians or educators. “It is a heavy book that is not for everyone, but I do think sometimes as a society we are more afraid of stories about the consequences and effects of violence than we are about violence itself, and that troubles me.”

Just as the books try to provide some sense of hope and healing, readers need that in real life, too, no matter how hopeless and helpless they may feel.

“I used to think of hope as a lighthouse, fortified against a sea of violent, cavernous darkness, but it’s very lonely to be a lighthouse,” says Neely. They now prefer to think of hope as a sea of fireflies. “It flickers and glows in small acts of kindness, in dreams for a better world, and in moments of connection.”

Amanda MacGregor works in an elementary library and blogs at “Teen Librarian Toolbox,” slj.com/teenlibrariantoolbox.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!